Through the recording of the noise of daily life and its own absurdity, the American-Spanish artist Ian Waelder incorporates into his thinking matrix the conceptual inputs to produce pieces and actions that reveal the silent activity. Some years ago he came to Chile to exhibit at LOCAL gallery, where one of its founders, the Chilean artist Javier González Pesce, talked to Waelder about laziness, disappointments, music and its implications in the different ways of production.

By Javier González Pesce | Images courtesy the artist

Javier González Pesce: I have the impression that skateboarding introduces you to the world from a different perspective, but there are mainly two ways that attract my attention, and those (according to me, I don’t know how to skate) have to do with vision and perception. One is speed, which somehow impedes focusing. The other has to do with an ability to read things in a formal way, mainly for the purpose of doing tricks (jumping, sliding, etc.). Somehow the surfaces of things stop describing things in themselves for their conventional functional understanding and begin to have a parallel life with a somewhat more subversive and creative identity, even sculptural. Does what I’m telling you makes any sense? How does skating transform you into a person who has a particular relationship to objects and spaces? How much has your understanding of reality influenced skateboarding, and therefore, how does this practice make you a particular artist (if at all)?

Ian Waelder: Yes, what you tell me makes a lot of sense. I suppose I can’t deny that this skating practice has influenced me, above all, on levels of sensitivity to what surrounds me. I think that everything you comment on about the formalities and questions of space is something that somehow I didn’t have to “learn to see”. That came to me thanks to developing an interest in apparently useless things that we surround ourselves with on a daily basis, and skating developed that even more.

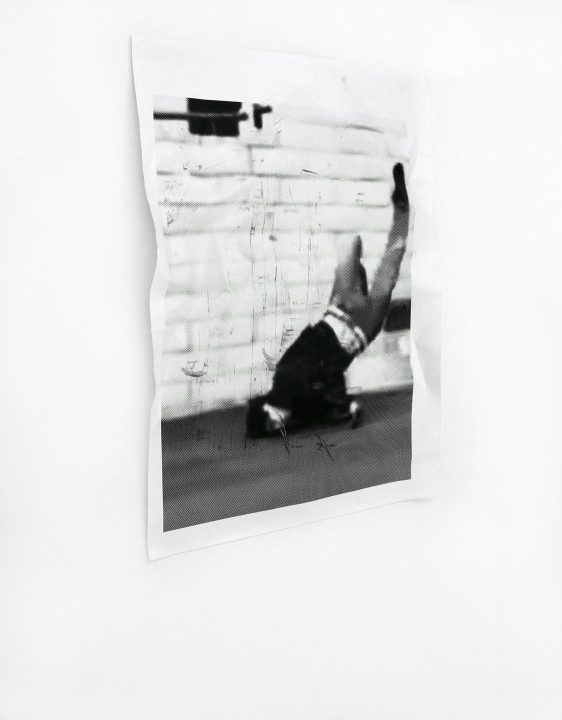

I didn’t have to learn to notice, but to question why I noticed all that, and that’s where I guess I started to express myself as an artist. But that’s something I’ve been able to see with some distance from myself. It’s a typical cliché, but at the end of the day art or the practice of making it helps some people to understand each other better, and I’d say that’s my case. In my practice, the idea of memory is always present, randomness, time, traces of experiences in things, even emptiness. Looking back, I remember returning home covered in bruises all over my body, with dirty and ripped clothes and shredded sneakers. I even left those traces in different parts of the city such as benches, curbs, handrails, etc. All that is a language, a code, and if I look at what I do, I recognize myself having lived those moments in a very particular way.

JGP: Those traces that you point out, that later end up being constructed as code or language, are ones that carry an energetic identity, not very pretentious, not very precise (in the formal sense perhaps related more to gestures than content or ideologies), aggressive and very loving at the same time. It is perhaps an energy that is at the base of many cultural movements, from Skate to Punk, as arts of living, of believing (or not believing) that are also ways of inhabiting. These ways of inhabiting, being containers of an aggressive and vital energy, hurt¾or at least leave marks of friction¾on the spaces in which this energy is released or performativity executes. One can recognize an area inhabited by skaters by their traces, which generates resistance from sectors of society, but I think they also complement the urban panorama as a kind of mysticism of the subversive. It makes me happy to recognize traces in the city that reconstruct forms of life parallel to the “must be”. It seems to me to be ethical, vital, healthy and charming. Some time ago I was reading a conversation between Borges and Sábato in which Borges complained about the “noise” of rock, which he considered lacking in nobility in comparison to chamber music. Sábato told him that he believed it was possible that his deep convictions regarding taste and poetry limited him with respect to the possibility of finding beauty in distortion, a lack of inspired precision or noise, but that this would be an almost generational and environmental problem. What do you think of the poetics of subversive work? You mentioned memory and randomness as elements in your work. Do you feel that sometimes you appeal to a collective memory that invokes nostalgia for common experiences regarding some forms of life?

IW: Mmmm, the poetics of the subversive. I think that art, in a way, is already subversive in its own existence, just because someone decides to do it. And that’s essential, because from these poetics come other layers that adapt to social reality and sometimes end up working. But it is also dangerous and perverse. I think there’s little room in today’s art world for the subversive: just look at what’s going on with Supreme, punk bands or whatever comes to mind. The mainstream absorbs it and makes it cool, but nobody questions anything. And today’s art world in a way absorbs everything and leaves little room for questioning or even confrontation. You need confrontation, but this whole moment of hyperdiscourse absorbs and justifies everything, so there’s no point in doing something subversive if you know it’s going to be accepted and somehow seek to be endorsed. This is the absurdity of most institutional criticism, which sometimes nullifies itself. The artist scores a goal to the institution, but has it theorizing about their criticisms and making that one more piece of content that passes the filters that they criticize. But I believe in a transgressive need in the forms of making, how to deal with materiality or to claim the role of the artist.

“I am disappointed by the lack of criticism and the prevailing passivity, as well as a high degree of hypocrisy in the art world. In a way, we artists are the weakest in the pyramid, but we have the most important voice and that’s not at stake. I’m getting more and more radical in that sense, I don’t know if it’s good but it’s what I feel. In art I like extremes, and it’s interesting to play all the cards towards that radicality when you are guided by values.”

For this reason, I miss more aggressiveness from artists, more noise, more distortion. The distortion, as well as the conversation you mention between Borges and Sábato, is a great example. It is like an altered echo of what is real and already accepted. It deforms itself. Lately, I am disappointed by the lack of criticism and the prevailing passivity, as well as a high degree of hypocrisy in the art world. In a way, we artists are the weakest in the pyramid, but we have the most important voice and that’s not at stake. I’m getting more and more radical in that sense, I don’t know if it’s good but it’s what I feel. In art I like extremes, and it’s interesting to play all the cards towards that radicality when you are guided by values. Does that make sense with your question? Maybe I’m deviating from the subject.

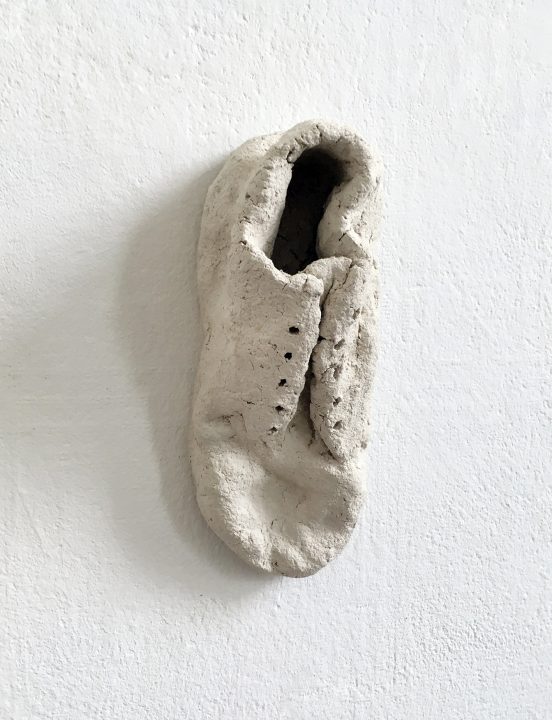

It is true that there is something pertaining to collective memory in my work, but I don’t conceive it in that way during the process. In that sense, I’m quite selfish and use my own experiences in the subtlest ways I can. From the use of old shoelaces to the fact of using a type of raw canvas as a work surface, or some recent works in clay that for me are a direct homage to my father and his occupation as a sculptor. Personally, my relationship with these things or materials is very strong and that is why I use them. But not everyone has that same connection and can therefore appear to be making purely formal or aesthetic decisions without any further meaning, something that I do not consider to be negative either.

JGP: But don’t you think that, no matter how personal the choice of specific materials may be, these actually involve a large community? Probably one that has lived an intimacy that, although specific, crosses your own personal intimacy? I believe that the world is full of intimacy that is in tune with others and that in this way they form communities in the silence and secrecy of the private, communities composed of people with similar lives who do not even know each other, and who constitute a collective force without knowing it. Sometimes art externalizes elements or poetics of the personal by making them public, a gesture in which these secret collectivities are recognized. Don’t you think that sometimes the experiences of the intimate become so intensely personal, but then you discover that in many houses there are so many others who suffer and get emotional in the same way you do?

IW: Absolutely true. It’s like when your partner leaves you and you listen to sad songs, and you think you’re the only one who identifies with those lyrics and at the same time you have millions of people who identify those songs with the same experience you had (laughs). What I meant was, if you ask me “why?”, I’ll answer this and that and blah blah because they are very specific reasons for me. But of course that comes up later and those connections you comment on are generated. There is an extimacy produced of certain things that you think are yours, but by sharing them you understand that you are not so special. The artists with whom I have most affinity with end up being those with whom emotional and personal harmony is produced. And I suppose that happens to almost everyone. But it’s not something I really have in mind while working.

“It is true that there is something pertaining to collective memory in my work, but I don’t conceive it in that way during the process. In that sense, I’m quite selfish and use my own experiences in the subtlest ways I can. From the use of old shoelaces to the fact of using a type of raw canvas as a work surface, or some recent works in clay that for me are a direct homage to my father and his occupation as a sculptor.”

JGP: What importance does music have in your artistic reflection?

IW: I think it’s the most important thing. Even if it’s not as obvious as other things in some works, it could be the presence of trace and memory. Or maybe I correct myself by saying that they go in parallel. Or the truth, I don’t know. Many things I simply do without asking myself, and then I analyze it better in time. Music is essential for living and I can listen to, whatever, let’s say some jazz and get to know the context in which that piece was made and think, “I’d love to do the same as what that drummer does with what I’m doing in the studio!”. And we all know that in art there’s rhythm and balance as in any musical piece. But I do the same thing when I read: when you see that a writer is able to transmit a whole idea in four lines and you think again, “Wow, that’s it”. In that sense, I learn more about art with a Bolaño book than by reading any other book that talks about art explicitly. So returning to the subject, I would say that the importance of music or literature is essential not only in artistic reflection but in me (us) as human beings. Everything else comes later.

JGP: I believe that works or art objects are the material parts of thought processes. These processes of artistic production would then have material (or other) parts that exist in the real world as well as bodies, but also metaphysical, abstract parts that are more like ideas. In your practice, how do ideas and things relate? What place do ethereal perceptual elements such as sensations, intuition, temperature, paranoia, speed, fear, taste, uncertainty, among others, occupy in your artistic ideology? Could you say that elements of this nature become elements of relevance in your artistic language?

IW: I would say that everything you mention is given in different moments of the day-to-day that give rise to a result that I gather as part of the work. I also understand art as that material part of a thought process, but we should not forget that everything around us is the result of an equal thought process. The fine line that differentiates it would perhaps be the symbolic level of things and the language used at a material and formal level, as we observe in architecture or design. And it’s good to keep in mind that nobody is asking us to “make art”, and yet some of us do it anyway. Even with so many things possibly not playing on your favor, like not having time because of other jobs or no money at all and still spend the little you have in a specific material. That is so absurd and fantastic. There’s a great deal of spirituality in art that’s hard to ignore, it’s dogmatic too, and for many it’s hard to understand if they don’t form or know how to set foot in part of the process. I understand it as a necessity. It is already curious to think about certain things without the necessity of having to transfer them to the material world. As curator, and friend, Sonia Fernández Pan made me see, even the thought is matter if we analyze what happens in our heads. In my work, I would say that everything goes from one side to the other. The material thing lands after the idea and in many cases it is the fact of seeing a gesture–the way in which an object falls with another, etc.–that gives the idea, and from there it starts again. I don’t usually foresee things very much. I see myself in a constant state of uncertainty in several aspects.

“I also understand art as that material part of a thought process, but we should not forget that everything around us is the result of an equal thought process. The fine line that differentiates it would perhaps be the symbolic level of things and the language used at a material and formal level, as we observe in architecture or design. And it’s good to keep in mind that nobody is asking us to “make art”, and yet some of us do it anyway.”

JGP: Is uncertainty productive? In what ways have you experienced this in your work? Art is sometimes a field of production (among other things) that makes use of states that for other disciplines would be nefarious. What states¾that in other spheres of production could be considered disastrous¾have served you positively to develop creative processes in the field of art?

IW: As the great Mladen Stilinovic said, laziness. Don’t you think? Being lazy has led me to find ways of working that I wouldn’t have encountered in any other way. Just being indifferent, or not paying attention to certain things, lets you find yourself in a sort of mental room where things start to make sense by accident. Uncertainty, or tension in my case, works because of that. Or to be sad or confused (laughs), the much-repeated cliché of the artist that falls in love with the wrong person, but it’s quite inspiring as a way to understand why you do stupid things sometimes. Lately I’ve been feeling quite antisocial or uncomfortable at parties or events with a lot of people–it gives me some anxiety–but then I feel my work helps me because it becomes even more of a refuge and gives me some freedom. But at the same time, I honestly wouldn’t mind trying to follow a more normal schedule for when I am in the studio. Being your own boss also allows you to be more exploitative and you end up alienating yourself from people you love. But as long as there’s good music…

“Being lazy has led me to find ways of working that I wouldn’t have encountered in any other way. Just being indifferent, or not paying attention to certain things, lets you find yourself in a sort of mental room where things start to make sense by accident. Uncertainty, or tension in my case, works because of that. Or to be sad or confused…”

JGP: There are times when I don’t see any sense in making art and then I think that in this world of production and productivity, artistic ideas are of maximum value. Our sensitive and useless work comes to make a cooling gesture to the accelerated and thoughtless world of the practical and productivity. I think it is valuable for artists to construct, invent and produce under sensitive logics, under the coordinates of research with diffuse objectives. That artistic production still demands our work, intellectual and physical efforts, love, energy, time¾all this for the production of elements that have no functional role in the world, a bit like skateboarding or music. Does what I propose to you make sense? What do you think the impact of this work without a productive product can be? Does art still generate hope for you?

IW: I’m very proud of doing things that nobody asks of me or wants, as much as it can be frustrating to others. I remember an anecdote from Mallorca when Alejandro Leonhardt came to prepare his exhibition for the L21 gallery a few years ago. I went to see him where he was staying and we talked all night about whether there was a need to paint an old lifejacket white, or whether to leave it in its original, raw appearance –all worn out– which was just as the object came. And from that we went on to talk about the form in relation to, whatever, a remainder of plastic he had, I think. For a moment I thought, “If someone is listening to us talking about this, they’ll think we’re out of our minds.” I don’t know if it was something I said out loud, but it was very funny. I think we have to defend that absurdity because that’s where the most interesting things happen, and therefore it may be useful for something after all. I remember something that made an ex-girlfriend nervous was that not understanding of why I should dedicate myself to something that was not functional, or that was not really understandable (besides from the lack of economic stability).

When you dedicate yourself to this, you create a gap against which you have to fight constantly and, no matter how masochistic it sounds, I like being part of that trench. Being an artist, one sacrifices a lot of personal things to dedicate oneself to their work, and if you want to come here to be understood then be prepared to hit yourself against a wall constantly. Bolaño spoke of poetry as a gesture, a fragile adolescent’s gesture that bets the little he has on something that he doesn’t know very well what it is, and generally loses in the end. This world of precariousness has taken us to a limbo where we mix work and our own time in the same bag, and sometimes it’s difficult not to go crazy with that or get depressed. But it’s an attitude of society outside of art that I find hypocritical because they tend not to take seriously those who dedicate themselves to art, but then are obsessed with the word “creativity” or the artistic. Artists of all kinds of disciplines flood the networks and rankings of influence, but few people take you seriously if you’re not already on the crest of the wave.

Part of that lack of empathy, or respect for the work of others, is given because it’s usually easier to give value to what you think you could never do. And a lot of contemporary art seems to be very banal if you are constantly compared to Goya (which I love). People laugh but I think it’s better to laugh with them. I’m not going to blame them either for having gone through an education that puts culture, art and the value of ideas at the bottom of an absurd pyramid. For me, art generates hope, yes. It has undoubtedly been my salvation, and it is also true that I am not capable of functioning in another field. Maybe someday I will need something to save me from this (laughs).

JGP: I really like what you say about “defending the absurd” because it seems to me that the “not absurd” is in some way a convention, which otherwise in many cases has no respectable justification. To live in a non-absurd way is in some way, then, to give in to the ways of living of others, based on the conclusions of others. Besides, with time in history we have become used to many absurdities that we later adopt as normalities. Skateboarding could be one of those absurdities that later, by insistence, become cultural phenomena, which gives this practice a rebellious but also artistic character. Somehow the absurd gives us laughter because it surprises us and laughter comes to celebrate that. In an interview I recently saw with Oscar Tuazón, he commented that the art object is something whose existence does not often have a reasonable excuse and that, deep down, it is something in the world of the “not absurd” that should not exist. Discontinuities in the world of the expected; anomalies in the plot of what has an operative sense. Now in relation to your work, how is it that these logics nourish your processes of production and thought? What mechanics of dislocation and critique do you use? How do you produce absurdities?

IW: I totally agree! But don’t you think there’s nothing more absurd than the current political situation? Donald Trump or Bolsonaro? That in Spain a party that the courts have shown is acting like a criminal mafia continues to win elections? Or that we’re all going to crash in a major social collapse because of the climate crisis and politicians don’t give a shit about it? Art is like escaping from that daily bubble, where the absurd reigns in its saddest sense, and entering another environment, a meta-absurdity. Although of course you run into situations in the art world that are difficult to bear, and that’s when you see that we’re not so different from any other field. But that’s another issue that I prefer to separate from artistic practice.

I increasingly believe that my way of working is purely intuitive and of letting myself go and reacting afterwards. And that’s when I see certain absurdities or ideas that when viewed coldly can be very stupid. But it’s a good thing that happens. It’s absurd and exciting to argue with objects. Getting angry with shapes or a melody, a distortion. Getting excited about accidents. All those absurd things that happen in a workplace. Even the word absurd has its thing.

“When you dedicate yourself to this, you create a gap against which you have to fight constantly and, no matter how masochistic it sounds, I like being part of that trench. Being an artist, one sacrifices a lot of personal things to dedicate oneself to their work, and if you want to come here to be understood then be prepared to hit yourself against a wall constantly. Bolaño spoke of poetry as a gesture, a fragile adolescent’s gesture that bets the little he has on something that he doesn’t know very well what it is, and generally loses in the end.”

JGP: We met in Chile in 2015 when you did an exhibition at Local. I think you were 21 years old and you were already a traveling artist who had done different exhibitions in art centers and galleries. When I was that age I thought I was the most interesting artist alive, then failure put me in my place. The experience of failing, of being rejected, made me a more modest person, less secure, less naive, not so idealistic. It definitely affected my energy and the conviction that what was going on inside me was of urgency and need outside me. When I see the production of young artists (pre-failure) (Bret Easton Ellis or Slint, among others), I see the energy of youth intact, delirious energetic convictions, pure and transparent. What opinion do you have about success, failure and youth?

IW: Well, it’s a question of determining what failure means for each one of us, or the idea of success. I already experienced it in some way as a skater, in that I had certain aspirations and my level perhaps reached a point that did not allow me to go further. At that point I was not enjoying it as much as when I started, despite starting to have sponsors and early media coverage.

That’s why I think I’ve always felt chilled in that sense and I take those things in a more natural and not so speculative way. But my parents also educated me very well (laughs). My case is a bit ridiculous because while my classmates were studying to pass high school and to be ready for the university entrance exams to be able to study for their careers, I decided to leave school as soon as possible because it took away my time to dedicate myself to doing other things that contributed much more to me, like “making art”. It wasn’t that I was in a hurry, but it was a pure need to want to do things. So my starting point was already being a failure as a student, and I didn’t have much to lose in that sense if the art didn’t go well for me.

It has helped me a lot (more than anything else) that, since I started, I have connected with a lot of artists older than me who have a lot of experience. From talking and getting to know their stories, it just comes as a standard to keep your feet on the ground and know that devoting yourself to this is a long run and that it is good to take it with some discretion. In that sense, to say that I started from failure–understood in its hardest sense– would be something ugly and clumsy to say on my side because, no matter how hard I work, I consider myself a privileged lucky bastard. Just by the fact of being here talking to you, I have an attention that other artists I know don’t have, and they deserve as much or more. I know very unfair cases of people who haven’t had one chance or who should have another. And the failure, or loser, concept is sometimes played in excess and trivialized. I always find it funny how Beck got popular by the Loser song, but that seemed quite honest. I now think of a great drawing by the artist Carlota Juncosa, where she illustrates a phrase by the songwriter Christina Rosenvinge that says, “Beware of the loser thing! To get used to talk about irony and being cursed is in reality very comfortable and easy.”

And answering the end of your question, I would say that failure (in art, in love, on video games, in life) I prefer to pose it as something inspiring that helps to get to another point. Success, I think, numbs and/or provides a false security and youth is nothing more than an attitude. But as a good friend said, “We won’t be here tomorrow,” so I prefer not to take things so seriously, even though I do. Success should be what my father told me the other day. He’s 72 years old and he says he feels that he’s living the best moment of his life. But it kept me wondering if I really have to wait that long? I think as young artists today we want it all very quickly, with great public exposure, and that leaves a lot of people in the middle-of-the-road or very confused. There are people who don’t know if they want to be artists or if they are satisfied with people seeing them as artists. That’s why I’m very suspicious about Instagram (laughs).

“Success, I think, numbs and/or provides a false security and youth is nothing more than an attitude. But as a good friend said, “We won’t be here tomorrow,” so I prefer not to take things so seriously, even though I do.”

JGP: When you exhibited in Local you locked yourself in the gallery space to skate, leaving the walls full of traces of the wheels of your board. We even built a ramp for you to do wall rides all over the place. You recorded the sound, which was then played back with very powerful speakers. So somehow the exhibition was based on traces (on the walls and audio). I, who knew your work through photos on the internet, felt that you had a fixation on images and that your work came from photography, but this exhibition at Local made me see it as a work that was produced directly in space and from an action. How do you communicate your interests through memory, movement and photography? How do you conceive this exhibition in Local and how does it communicate with the rest of your work (towards the past and the future)? Do you feel that this piece could be a kind of sculpture, produced from absences and evocations, about how fundamental the dialogue with space within it is?

IW: Yes, actually at that time I was very focused on the expansion of photography, but it was something that tired me. To depend on the image seemed boring and very easy. That’s why it was great to be able to do that exhibition at Local. It was an idea that had been in my head for a few years already, much like a fantasy. Previously I did a work in which I scratched the wall with wheel dirt and overlapped it with a negative image of the same marks made elsewhere by other people. It was fun to see how the results of some movements generate these unconscious marks, which always end up coinciding.

The proposal for Local came a bit from that. I wanted to skate the walls of the gallery myself and introduce that language into it. The same invasion that takes place in a public space, such as a plaza, and moving it into the exhibition space which is, curiously, a house. Skating, building the ramp with you, and then recording the sound with Montaña (Rodrigo Araya) was a great experience. The truth is that I had no idea what the result would be, but in the end it went well. There were a lot of people who didn’t understand anything, or what the sound was about. It was a noisy box. People were a bit confused, but that was something I was interested in. Like what you said about distortion. That’s why I told you that I didn’t want the text you wrote for the show to explicitly describe what was happening, because it would have lost all interest.

So this work was something that marked a before and an after for me. Well, I kept talking about everything I talked about before, but I didn’t depend on photography. The image was still there– with the sound and what was evoked in you–and the memory was in the sound and the strokes, with the movement being the whole of it. Since then, that work has helped me to simplify things more and more, and at the same time helped me lose the insecurity to try other formats without having any idea how to handle them. Since then, my works have ended up in a variety of forms beside sound, text or painting. Now I see myself finding a balance between everything, which remains horizontal.

“Suddenly I’m in a place that offers me the opportunity to experiment but I still have to learn how to profit well from everything. Sometimes I wish I could just work on the street, like Hammons. I like life in the studio and I need it, but sometimes it becomes too much of an office with so many computer work and that makes my existence bittersweet.”

Later I developed this work in different ways, such as in Salón (Madrid), in the show I did together with the great Felipe Mujica, curated by Carolina Castro Jorquera. In this show, I skated on the floor around Felipe’s piece hanging from the ceiling. I wanted to talk about all the different breaks in the floor tiles and skating on them was, for me, the best way to do it. A year later, for the opening of the new space of the gallery L21 in Mallorca, I invited friends from my adolescence to skate and acted more like an orchestra conductor. The result was more composed and not as raw as the previous ones. Whenever I have done these works I have had sculptural works in mind as a reference. In L21 I was constantly thinking of compositions by Fischli/Weiss or Erwin Wurm. I wanted the installation to sound like one of their photographed sculptures of objects in equilibrium or Wurm’s One Minute Sculptures. And they are photos!

JGP: What are you currently making in terms of artistic production? What are the issues and procedures that keep you producing? Have these varied a lot in your trajectory?

IW: I think they’ve varied in format or medium but the line that brings them together is still very similar to when we first met. And I can allow myself the pleasure of going from one thing to another as someone who cuts onions and, on the other side of the kitchen, peels potatoes with the same knife (something not very recommended). In 2017 in Barcelona, I was sharing a studio (Salamina) with painters (Rasmus Nilausen and Pere Llobera), and although Rasmus was away all year at the Jan van Eyck Academy, his work remained in the atmosphere along with Pere’s tireless activity. Maybe the spirit of Sebastián Cabrera, another painter who gave me his studio space when he went to Lima, took hold of me and motivated me to get my first stretcher bars and try different canvases without having any idea of anything. Pere taught me how to mount them and stretch the canvas correctly by a WhatsApp conversation, which made it more fun. But my work rhythm is so slow… I need things to calm down and rest for a while. I can do things in five minutes but it’s good to watch them and let them rest for a month or more if necessary. So since then, I have been with these works in raw linen–used for the restoration of paintings–and now I find myself trying iron, wax, clay… thanks to the fact that in the school where I am currently studying, in Frankfurt, there are workshops for all that and I am learning technical stuff. I’m also working with papier-mache a lot and for the upcoming show in L21, I’m getting the chance to cast some remains of cardboard tubes in bronze. I’m also working on a show with Sonia and I’m preparing a sound piece that consists on a rhythm that happens by throwing all my shoes down different staircases. The topics are still mostly material memory, what remains in things from mostly random acts. I don’t know, I feel very easy-going now, like throwing things on the floor and seeing what stays there or what is stored in a box at the end of the day. Sometimes I’ve seen myself a bit like you, when you say that you weren’t entirely used to the studio practice, to the processes that are generated there. Suddenly I’m in a place that offers me the opportunity to experiment but I still have to learn how to profit well from everything. Sometimes I wish I could just work on the street, like Hammons. I like life in the studio and I need it, but sometimes it becomes too much of an office with so many computer work and that makes my existence bittersweet.

* This exclusive interview for Rotunda Magazine was subsequently incorporated into Ian Waelder’s first monographic book, “Looking, Finding, Living, Sharing.”

Images

1. “Wrong” #02, 2014. Laser print on 90gr paper with marks and dirtiness after being dragged by the floor of places where people practice skateboarding. 59,4×84 cm

2. “After A Hippie Jump”, 2014. Solo exhibition at L21 Gallery, Madrid. Part of the installation views.

3. Portrait by Maïly Beyrens.

4. “An Enjoyment That Consists Of Testing And Playing With The Resistance Of Materials”, 2015. Spray paint dust and marks of many different materials and objects found in the studio of the artist and that have been dragged through the floor of the exhibition space. Site-specific dimensions.

5. “All my shoes (Spooky Drums. No. 1)”, 2018. 7:11 mins, loop. Stereo.

6. “I used these shoes for a few months” (March/April, 2015), 2016. Shoes casted in bronze, hand painted, black shoe laces. Variable dimensions.

7. “Suede”, solo exhibition at Galería L21, Mallorca, 2016.

8. “Who Would Be Interested In An Empty Parking Lot?”, 2018. Solo exhibition at the Project Space of the Finnish Museum of Photography, Helsinki. Part of the installation views “All The Times I’ve Fallen Since 2008”, 2018. Stereo, 1:10 min. in loop. It plays all the audios of the video recordings of Waelder’s falls on a skateboard since 2008. It plays once every 10-15 minutes

9. Portrait by Nadine Koupaei.

10. “Wet (Third One In The Box)”, 2019. Papier mache. 28 x 11 x 10 cm.

11. “One knee misses the other”, 2018. Found remainder of a wooden chair and clay. 67 x 64 x 27 cm.

12. “Aaaaaahhhhh Uffff”, 2018.Remainder of cardboard tube casted in bronze (patinated), plaster strips. 34 x 41 x 16 cm.

13. “I remember better days”, 2016. Found iron bar, used sneakers. 29 x 237 x 15 cm.

14. Recording process with Rodrigo Araya for the solo show “The Noises, The Traces and The Marks” (2015) at LOCAL, Santiago. Photography by Javier González Pesce.

15. Test and recording process for “All My Shoes (Spooky Drums No.1)”.

16. Recording process for the installation “A Nice Reason To See Each Other Again” (2016), part of “Suede” at L21, Mallorca, in 2016.

17. Video register of “El Biombo y El Eco” (2015), bipersonal show with Felipe Mujica at Salón, Madrid. Curated by Carolina Castro Jorquera.

Español

Español