The work of the multimedia artist Nicolás Rupcich comes from the crossing of nature, science fiction and reproduction of the image. In these possible lines, it is where the search for an immanent truth of the state of the mind of the things, he does not find answers, but processes that respond to the new mechanisms of reproducibility. Thus, he confronts us with the dilemma of what is real, where the perspectives are more diffuse than ever.

By Carolina Martínez Sánchez | Images: courtesy of the artist | Translation and special thanks to Jacob Sheehan

Carolina Martínez: Your work comes from a timeless obsession with image and reproducibility of perception; from the contemporary obsession to reach reality through an equated construction of it. It is said that the “sublime” and true vocation of art today no longer exists, and that it has been referred to extend itself to everyday life and be a projection of this, where technology and mechanism are central to its operation. What is the vocation of art that is manifested from and through technological devices that would be able to achieve reality by building an image?

Nicolás Rupcich: Image management and digital tools are something increasingly common in our society, but between the use of those tools and creating art, there is still a considerable distance. I personally do not care about the “one liner” works, which are those that could be framed in the fusion between the mediums to produce images, art and society, but I think what ends up defining whether or not there is a process and project that retains any value beyond the medial fusion and what’s real; it would be a model of thought that continues to progress in each artist who goes beyond the use of specific tools. There are attitudes and thought patterns, that one sees how with time settle and take shape. I think that’s more important to focus on when trying to understand and identify something as a work. The random gestures that are often like shots in the air due to certain circumstances resulting in a target, can be interesting in a logic of shock and / or show, but distance themselves from the processes in which one identifies a universe of references and production conditions, framed in the way of understanding the world of a determined author.

Many times I find it funny to hear the terms “art and technology” or “art and science’. Not because something this programming with processing, generating automata machines, applying concepts of biology, working with plants, etc., one will be able to label under genres so laden and broad. I do not deny that there are many cases where it is completely valid, but in many it is nothing more than a bluff with which space at institutional and / or commercial level is gained. For me, an example of ‘art and technology’ is when NASA sends us images of Pluto across thousands of kilometers in outer space and finally reach our cellphone, by all means, to me that seems to be a poetic, artistic, scientific and technological act. I find it even more interesting to think about the fact that said probes carry cameras of a much older technology than the latest generation of cameras, of which we have access in the moment we receive those images. This is because in the moment when the probes where sent, in many cases years ago, NASA scientists decided to implement digital photography equipment that has been tested and work against all odds, if they send the latest generation of cameras they run the risk that the equipment may not work, so we can understand that the images that we receive today from Pluto or distant parts of the universe are the result of old cameras, of an inferior technology and resolution to our present; that is, in a sense we receive images from the past in order to understand our present. I find it absolutely interesting that ‘halt’ that occurs in relation to the logic that technology must always be a network of advanced gadgetry and be up to date. I think in the “new media” there’s lacking a large dose of humility. There are very few cases where people who work with technology and art are actually incurring technological advances, and the post-production of images is something so day-to-day that naming it as “new technology” is somewhat alarming, and is what generally incurs critics that their relationship with those tools is so precarious, that any digital operation far outweighs the problem of remembering their own passwords of their online accounts.

“For me, an example of art and technology is when NASA sends us images of Pluto across thousands of kilometers in outer space and finally reach our cellphone, by all means, to me that seems to be a poetic, artistic, scientific and technological act.”

CM: What led you to work with topics (or problems) of nature, science fiction and image reproduction? Was this concern what led you to be an artist and work this out from there, or is it that honing your work you unleashed your interest in this constructed image and hyper-reality?

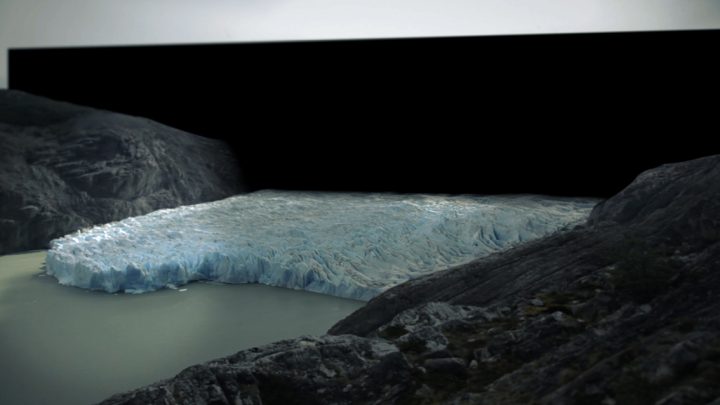

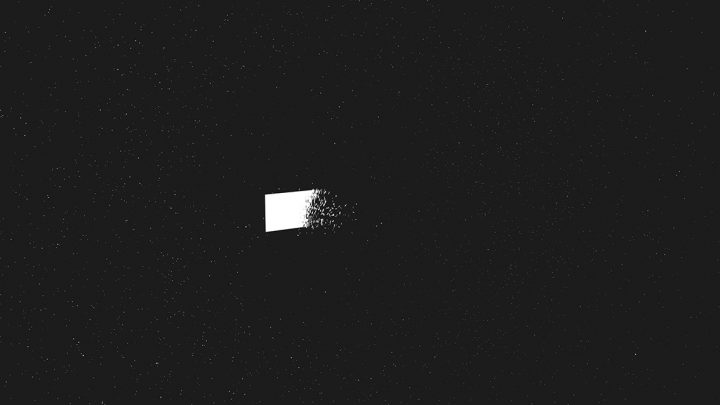

NR: As a main idea, I could say it’s the understanding of nature transformed into a fictional space, not only referring to the problem of artificiality, but through the representation of natural areas our notion of terms of definition, contrast, sharpness and saturation has shifted; characteristics of the nature of digital images displayed on the screens today are our tools for excellence. From there I derive the importance of the idea of a screen as an iconic object with which we establish communication. This has been a major focus of my work in recent years, not only as a support for the images I produce, but more and more I incorporate it in their own objectuality. I think that the very physicality of the screen over time is giving us signs of where our relationship with space of representation is going. More and more the screens continue to be thinner, pointing to an absolute transparency between the object and the space they have, so that the fusion of real space with virtual is something almost evident. One operates in the phone screen as you move somewhere, that is the simultaneous interaction of two types of spaces, which are continuously merging into one another.

Science fiction in any case has a large influence on many of my works by the logic of understanding artificial spaces as part of reality, simulation, etc., but not just the cliché of a dark dystopia, but dystopias that carry a mood of a poetic condition and at the same time critical. A great example of this is “Stalker” by Andrei Tarkovsky. In this case, I understand the condition of timelessness as a key point that operates as a significant benchmark in many of my recent works.

“I think that the very physicality of the screen over time is giving us signs of where our relationship with space of representation is going.”

CM: What is it that you are searching for and that offers you the picture of nature and of the city? How are your processes and methodologies to build, deconstruct, and decipher each one of them?

NR: The truth is that it’s super random how I work. All projects are based on processes, finding ways of how to develop a work, and most respond to a collection of material: on the street, screenshots, drawings, among others, and there are decanting constants of the references. Although recently what has me occupied is the theme of light, it is becoming increasingly important to me as a thing in itself, and all this is what will determine the type of images I’ll have. The dialectic of light and darkness, because obviously when you refer to the latter, you mean a problematic light. In German there is a word that refers to something sort of like an animus, not in a sense of humor but like the soul and sense of things. In this sense, there’s a kind of animus of the light and the darkness that goes through the whole work, and that’s what I’ve been solidifying in recent years. But they can either be images of nature or city, or abstract animations, even objects. What interests me is that the images or places have certain personality, that precise animus which often can be associated with death. It’s in regards to thinking about a time that goes beyond human life, which escapes our perception of it and its temporality. For example, I almost never show human figures in my pictures. Or a time to this part, I’m struggled to look for frames in which it is almost impossible to tell where it is.

“What interests me is that the images or places have certain personality, that precise animus which often can be associated with death. It’s in regards to thinking about a time that goes beyond human life, which escapes our perception of it and its temporality.”

CM: In this experiment what do you do with the various methods and devices that try to capture and reproduce the image of reality, building an “imaginary museum” with all these processes, how do you keep, or fight, the division between the reflection you try to build from your work with the real problems of the matter, is this the image as fragmented reproductions of something else that’s real?

NR: I could even become opportunistic do a critique of the phenomenon occupying the medium itself. The truth is, I have yet to resolve this dilemma, but it is necessary and essential to make visible what one sees in this representation, and make visible the presence of the media and put it in crisis. On the other hand, what I should say is that I am not condemning this, I’m not saying “technology is evil”, and that it is a larger problem. This is the constant confrontation between what one loves and hates at the same time, this duality, which is also reflected in what I do. It is difficult to take care of all aspects involved, because I’m certainly aware that entails contradictions, but I don’t have my work 100% clear. It would be pretentious and rude of me to say that one understands everything you are doing, there are always loose threads.

Faced with this question today is to face the problem of art always like a painting that reflects on the issues and problems of painting.

“This is the constant confrontation between what one loves and hates at the same time, this duality, which is also reflected in what I do.”

CM: One of your main supports is video, categorized as video art. What are the main advantages of constructing a narrative with this medium, and what is lost? Imagine the latter becomes part of the conversation.

NR: I fell into video by the possibility that the media presented me as a container for multiple medias in oneself, painting, sculpture, performance, animation, music, etc. Everything could be contained in a video, that was one of the main notions at first that led me to work with this medium. Now what it is what’s won or lost: it’s simultaneously the relationship over time. Understanding how an edit can completely alter the sense of a story or how the difference of a couple of frames can determine if said cut is effective or not. In that sense, it’s an interesting notion established with the problem of editing or montage by Walter Murch, who has been editor of such films like “Apocalypse Now”. He says for example, that the blink of a person who is talking on camera signals the end of an idea, a punctuation. I find it interesting how according to his observation and years editing, comes to understand certain phenomena that influence the way one can construct a story to have given fluidity or break with certain patterns.

This is given by a relationship with the material for a relationship with an understanding of time itself as the material, to be able to see details time and time again; able to go from one point to another and incur connections at first glance seem almost not to exist, but the net that one can build is a construction of a time and that understanding when I think working with video is fundamental and enriching. At the same time, the renderings, the interminably review materials, having to “see a period of time” to correct if something is right or not, results in time-consuming work that can be considerably larger than producing a two or three dimensional static image.

Spontaneity is also lost. The relationship with reality is lost and can even be alienating. That’s why I want to leave some of this dynamic and go back a bit to being manual.

“In Chile it is like that ecstasy by the “technological innovation”, which is very easy to get lost in instrumentation that are just for show.”

CM: Today you’re working between Germany and Chile. What were the main reasons for deciding to work in Leipzig? Did it have something to do with a search that caters specifically to your work, or that in the Chilean local context it’s still very difficult to develop a body of work based on video and media?

NR: There were several occurring factors. On one hand, I was interested in concentrating on the production of my work. To be able to produce in Chile, besides being an artist, you have to have another job that allows you to pay bills. While in Germany, where I was able to go via a scholarship, I didn’t have to have a side job; you can spend all your time dedicated on your projects and it takes about half the time to carry them out. You can read and try (and risk) everything that’s needed while often in Chile that occasion of testing is lost, a product of this time constraint. In Germany, I can be in a continuous process between work and projects, where some were unfinished others ended up as completed works. Although, that’s something that only gives you the opportunity to be trying things.

On the other hand, I was interested in seeing how the art scene worked there. At the end of my studies in Germany, I was clear that the anxiety that you experience here can be calmed. In Chile it is like that ecstasy by the “technological innovation”, which is very easy to get lost in instrumentation that are just for show. Being in Germany, you are in contact with works and projects that have advanced and have been able to bring that technology to a real point of innovation, and not stay in the show.

CM: Today it’s possible to visualize a tendency to experience and work more with these supports between national artists. How do you see this “new scene” of new media & video in Chile? What are your reflections and vocations? Considering this a tradition regarding political issues and the present. How has your change and evolution been?

NR: There are some Chilean artists who have very serious research in this area, and that go beyond the mere technical fascination. But I think is pretty common that many video works fall into a sort of “abstract journalism”, which still has its roots in the documentary aspects of the medium that has not yet been freed from video art.

At the other extreme, there is a generation of very young artists who have a reference of the post internet era with an aesthetic of 90’s recovery that’s stuck there, in the aesthetic aspect.

There are several aspects. But I’m not sure where all of this is headed today, but I do believe that things that have more distribution are usually super complaisant. They are speeches that are easily digested, they’re unproblematic, or you can project many conversations over them, almost like a blank canvas.

CM: The imaginary of your work comes from many places. In large part, it’s not because of a specific geography or context if not with structures and paradigms of contemporary visuals. From where and how do your processes become established in images, leaving aside that kind of autobiography to which so many artists undertake to build their speech?

NR: It is difficult not to be formed within something that is quite intuitive. As I have already mentioned, I have a series of references that are very notable.

For example, if I name Richard Serra there is immediately a feeling of something that is determinant, dense and consistent . In that sense, there are certain artists that you could define by the violent way they acquire their visual and / or formal aspects. Or Gregor Schneider, where there is something extreme in his aesthetic solution. In a similar way, this is what I look for when I work with the subject of light. Grazing with the minimal, finding that unique and decisive gesture. In the process of capturing images this is sometimes difficult, since the result -the image reproduced – does not contain that force, you will have images that manage to have or embody that determining animus and others that do not. There are some gestures I make which are based on that force, which many times may seem to only be motivated by the aesthetic but have actually been executed under those decisive decisions. Referring to the autobiographical component, I think that’s exactly what you don’t need to do in visual arts. They’re the components that begin to cross your work transversally as a backbone that’s shaping the discursive nature of your work, in my case it’s the experimentation with light as I mentioned, or the subject of death and temporality. And taking this into consideration, I unconsciously choose places, locations, or images, that respond to that animus that goes through my work today. This is how I can choose from cliffs in the south, to be filming swamps for hours. They are unstable and timeless limbs.

“They’re the components that begin to cross your work transversally as a backbone that’s shaping the discursive nature of your work, in my case it’s the experimentation with light as I mentioned, or the subject of death and temporality.”

CM: The construction of an image from the reproduction of a part of reality used to take a good amount of time before reaching its visible result; with this its imitative character of reality was understood. Today, capturing and reproducing images occurs in real time, influencing and affecting people’s perception of what is true, losing perspective and objectivity. How do you include this in your pieces and clearly establish the point of criticism so that it is not an image within that chain of floating images that overlap real life?

NR: Of course, photography today is referring to itself, it does not appeal to a reality. Here we return to the problem of how to make visible that what you see is an image that’s truly a representation of something, and it’s not the image alone, almost like a tongue twister. But a lot of the gestures I’ve done in some of my works work under that logic. For example, when I was filming the marshes, I used a plug-in that’s used in recording extreme sports, it fixes the image as an eternal, where the perception of space and material is lost. You can realize that there’s a manipulation of the image, but very discreet, that wants to unveil the moment of capture or the represented.

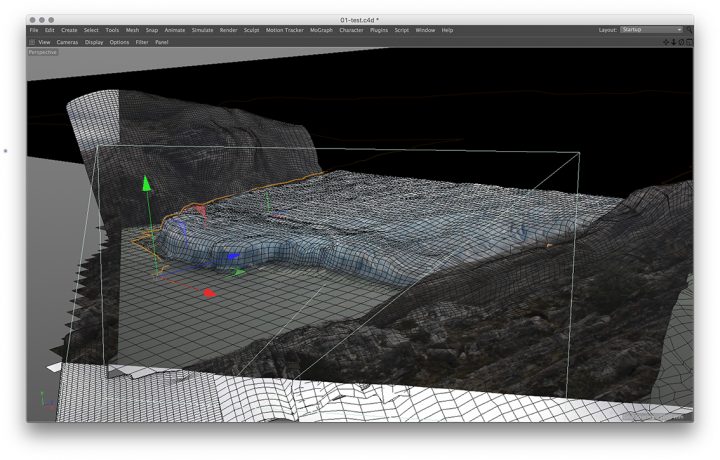

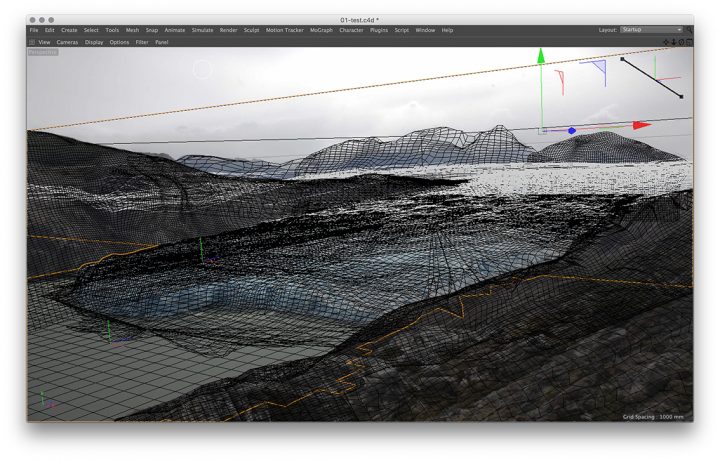

Continuing with this, I believe that what allows the image to articulate and what’s fundamental working with images today is the aspect of post-production, but this is understood like a series of ample operations in which the images of origin, whatever they might be, are manipulated based on their materiality and structural conditions. That is to say, not only granting them a character by color editing or filters but understanding how malleable it a 3D file, photograph, or any type of image behind a screen and in different programs can be. In this sense, it’s fundamental to understand the instability and / or fluidity of the images as a foundational problematic with which one must work and question the medium itself.

CM: Personally, I’m guessing that in video and new media you are evoking what we have already talked about, the way in which images and reality are constructed and reproduced, almost superimposed between them. In your photographs I see the desire to verify and patent the construction of life, either trying to perpetuate traces of civilization or raising scenes that have nothing to do with characteristics of that place. Both definitely have that of the “imaginary museum”. How do you share your pieces and projects? Do you visualize the format from the outset, or at the end of the process does it manifest itself more adequately than the other for certain thoughts or questions?

NR: The great majority of the projects start with the decision to go to certain places, and being there is the same place and environment that begins to deliver the keys to how to start. Other times, it’s the kind of images that appear in your mind, and from there you start looking for how to translate them. Here we have more digitally processed images that are involved. But my works that use photography and the landscape have an accidental factor. They’re very long processes that lead you to understand the images you are collecting; Review all the material, think about what’s really going on there. Although, when I work for a long time filming, this incidental character is disregarded.

The photographic act for me functions as an exercise that finds its solution depending on the project, the light conditions and surfaces that are found. For example, in “Der Tod der Sonne”, 2015, I only worked with long objectives of 200mm up to 600mm because these tools delivered the type of framing in which the details take center stage and the coordinates dissolve. This translates into a research work behind the lens that concentrates a series of observations on how light behaves in front of different surfaces, an exercise that is quite complex in relation to simply making an open plane in front of a landscape, It is intrinsically sublime or suggestive. So that for the resolution of each project, I propose the investigation of the solutions that work according to the subject in particular from the moment the eye is behind the camera until the moment after the work with the images is decant in a Post-production system relevant to the case in question. In that sense, my work lies in experimentation, although much of my work is framed in digital media, I look for each project a different resolution. It seems to me that in that exercise lies the potential of the development of each artist, in experimentation. The formulas are a condemnation.

“My work lies in experimentation, although much of my work is framed in digital media, I look for each project a different resolution. It seems to me that in that exercise lies the potential of the development of each artist, in experimentation. The formulas are a condemnation.”

Lately for me, it’s more relevant to focus on the notion of working with “animus” rather than with concrete meanings. This has a strong relationship with music and the construction of these spirits, which in the case of my works is usually connected in an opaque state that is opposed to the logic of a technified society for productivity without limits. In older works, there’s a more direct and evident criticism of certain social phenomena, in the case of my more recent works there is the same intention, yet contained in thicker layers that also appeal to sociological states, not only concrete ideas, that are translated into concrete visual forms. The work that is framed in this last line of work usually takes much more time to develop, countless tests and errors that along a process are taking shape along the way, and which in parallel is building the meaning of work.

“Lately for me, it’s more relevant to focus on the notion of working with “animus” rather than with concrete meanings.”

CM: What projects are you working on today and what is next on the way?

NR: For the time being, I’m participating in a contemporary Chilean photography exhibition at the Manuel Álvarez Bravo Photographic Center in Oaxaca, Mexico. Then I participate in the exhibition ‘Elsewhere is Nowhere’ in the National Museum of Fine Arts of Taiwan together with German and Taiwanese artists, then next year this same show will be presented at the Kunsthalle Exnergasse str. in Vienna, Austria. Next year I have samples in Leipzig and others that are being discussed in which other places I’ll present new works that I am working on.

Español

Español