Lehman Brothers uncovers, among its fundamental ideas, the eco-geopolitical panorama that has been damaged by the annihilation of natural resources. Adding to this are the group’s own land explorations that raise questions about the boom and bust cycles of the extractivist industry and the varied phenomena it produces. One of these was the trip that the Danish art collective undertook to the Atacama Desert in Chile, which is a geographical region recognized as one of the great enclaves of the mining industry.

By Rodolfo Andaur | Translated by Hugo Hopping | Images courtesy of Lehman Brothers and SixtyEight Art Institute

The impact of extractivism has become a matter of research for contemporary art. Artists and collectives have turned to this issue because of the physical and intangible consequences brought about by neoliberalism. That being, the weakening of governance and the constant deterioration of the environment, caused, in part, by the impact of anthropogenic waste.

These issues have been, in part, the basis of a series of works and research carried out by Lehman Brothers. This Danish art collective uncovers, among its fundamental ideas, the eco-geopolitical panorama that has been damaged by the annihilation of natural resources. Adding to this are the group’s own land explorations that raise questions about the boom and bust cycles of the extractivist industry and the varied phenomena it produces. In 2018, Lehman Brothers undertook some research on this topic in the Atacama Desert in Chile, which is a geographical region recognised as one of the great enclaves of the mining industry since it currently has 52% of the world’s reserves of lithium [1], a metal highly sought after in the market for various technological devices. During the 19th century and through the first decades of the 20th century, saltpeter (also known as white gold), and which became the main fertilizer for agricultural fields in North America and Europe, was exported from the desert.

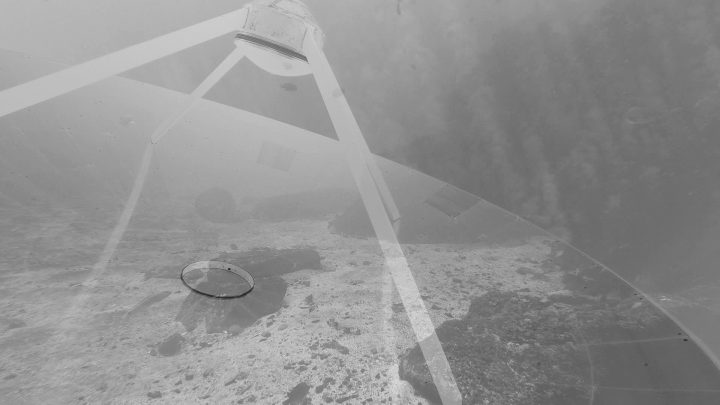

Lehman Brothers, in response to this context, installed the work called Pendulum Rising at a low-grade salt mine near Victoria, and on the edges of the Salar Grande de Tarapacá. [2] I must emphasize that nitrate, as well as ammonia, were great rivals in the fervent export and import escalation that took place at the beginning of the last century. This fact caused the collapse of white gold exports with devastating consequences at the beginning of World War I, with the discovery of synthetic fertilizers in Germany, and ending in October 1929, with the securities market crash in New York. Since then, the various towns, offices and encampments related to the nitrate export business were stripped of their privileges, whereas their abandonment and dismantling became part of everyday life.

In this unfortunate story, the post-apocalyptic atmosphere in which the artwork Pendulum Rising [3] was set, also exposed the historical disaffections that these compounds convey in the socio-political landscape surrounding the Great Depression. That is why, through the relics of this recession which affected the transnational market and that today lie scattered in the middle of the desert, I could argue that, despite this trance, the dispossession of some minerals – a practice known in countless numbers of territories – has been and continues to be a sponging business, since the capital extracted will never be returned to the land.

On this occasion, Lehman Brothers moved their research emphasis to the mountainous Pacific coast–specifically in the southern part of the Atacama Desert–where they found a small cove of fishermen called Chañaral de Aceituno. This place has a geography that accounts for several centuries of domination of the mining industry by a couple of fiefdoms, mainly European ones. Today, some of these are headed by corporate groups, who have battered the unfortunate people of this region under the dominion of the nation of Chile, a country of extremes, not only from the geographical point of view but also from an ideological one, taking into account its decadent neoliberalism.

Also, the surroundings of Chañaral de Aceituno have weighed suspicious convictions that are related to the maintenance of artisanal fishing work, and at the same time, of the mining work that seeks to shovel the high costs of maintenance for these places. This adds to the research by this group of artists into the dystopias that surround extractivism, as well as into capitalist dogma, and the development of globalisation.

From these determinations, the primary narrative of Lehman Brothers is confronted with the reality of these communities, which have undergone the same transformations that their biodiversity has experienced. In this sense, although capitalism promotes a tangible enclave, at the same time it’s a cultural construction as the Mexican feminist philosopher Sayak Valencia has written: “First of all, it is important to highlight that capitalism, in addition to being a production system, has become a cultural construction. It is important to evidence this fact since through our reflections we do not refer only to the economy but also to its effects as a bio-integrative cultural construction”. [4]

Certainly, the current situation in capitalism has exceeded its own history and there is no doubt that its detrimental effects appear more frequently in the third world, even more during these months of chaos and uncertainty in the face of the pandemic. These dilemmas have already been elaborated by the ideas of some artists and thinkers who plot, in their projects, the debris that this economic ideology has left: “Capitalism changes everything. It has altered our relationship with Earth. It has torn territories apart and uprooted their materials, transporting them over the surface of the planet as traffic between nations and markets”. [5]

From the arguments that I have presented, I can understand even more that the research of this group reveals the invisible aesthetics of capitalism and how this ideology keeps Chañaral de Aceituno implicated in the immeasurable consequences of global capital. However, it is well known that the global art scene – which attempts to reveal these ecocides – omits those who arbitrarily alienate and commodify nature.

On the one hand, globalisation, ‘that unidentified cultural object’ [6] shows that the effects of alienation and commodification appear as phenomena that look to be properties of the emergent technocracy of late capitalism. On the other, it does not materialize into a holistic dimension as a regime, but ends up only revaluing the exploitation of the territory as a whole.

Taking this into account, it is clear that Chañaral de Aceituno has never been considered as an ecosystem for globalisation, but rather, in the words of the Chilean economist and regional theorist, Sergio Boisier: “As a stronghold for the implementation of extractivist projects. What’s more, globalisation, it is said, carries the threat of breaking the ties of territorial identity, transferring them to a corporate, functional world, in which it would be more important to be a ‘citizen of Coca-Cola’ than of this small bay of fishermen. However, this will never happen; in truth, what globalisation generates is a dialectic of identity: the greater the danger of a total alignment, the greater the tendency of people to reinforce the local (territorial) dimension, like a recovered space of solidarity, perhaps as the only way to overcome the argument between ‘globalising yourself or not’, opening a space to the question of how to control this process in order to turn it into an opportunity for development.” [7]

The truncated social structures with which the mining camps are maintained have also reinforced this local dimension. A no less overwhelming detail of this capitalist and globalising situation is the one that appears when Lehman Brothers approaches the ecological site of Chañaral de Aceituno as their artistic research. Here they observe the impact of the mining industry on the ecosystem and study mammals in this area, specifically the Humboldt penguins and the different species of seabirds and cetaceans that have survived the dramatic and substantive poisoning of the ocean as a consequence of the mining industry.

The Pacific Ocean, which has little or no restfulness, is itself an endless migratory surface for untamed wildlife. It is quite striking as this sea in particular, presents the whales’ trajectory throughout history. This has also been highlighted in some novels, and which at the same time have allowed me to become aware of the infinite variety of raw metals and materials that larger-scale extractivism exposes in that particular corner of South America.

Therefore, I dare to comment that this group of artists has presented me with a multilateral introspection to deepen the decolonisation of nature, as stated by the American cultural critic T.J. Demos: “…decolonising nature entails transcending human-centered exceptionalism, no longer placing ourselves at the center of the universe and viewing nature as a source of endless bounty. Fields of inquiry that have recently investigated the terms of such a move include speculative realism, new materialism, ecosophical activism, object-oriented ontology, elementary politics, and post-humanism, each variously proposing innovative methodologies of post-anthropocentric analysis.” [8]

These post-human landscapes are epicenters for studying knowledge in a transversal way. They engage and critique cruel neoliberalism and a pernicious anthropocentrism–the very forces that disrupt the commitments that I (and we) all maintain, as a community, with the environment. In this way, the sightings of immense cetaceans, especially of the ‘Antarctic minke’ or the so-called ‘fin’ whale, reveal in a cosmogony that relives the clash between colonized nature and the fractures that our neoliberal system exhibits.

Additionally, science has drawn up a project for the exhaustive study of these large mammals, but the poor economic outcome that is tied to these mining camps has led to a part of its population becoming dedicated to the ecological-cultural tourism industry. This undertaking has revealed an aspect that does not arouse interest to highlight critical cultural aspects, but rather implies the resurgence of a worldview in favor of globalisation.

Another aspect that reveals this exploratory journey is related to the dark romanticism of Herman Melville, specifically in his epic work Moby-Dick, where whaling –that stubborn fight against the natural balance–has repercussions parallel to the state of disarray oceans find themselves in today. Without going deeply into these last and crucial lines, it is quite evident that whales constantly face the verb ‘extract’, which is key to understanding the dynamics of their evolution, through an increasingly decimated maritorium [9] due to pollution. More specifically, whales have effectively been absorbing into their skin the tons of tailings (residual rock waste) that large mining dumps in the ocean. In this way, we cannot deny the susceptibility of these monumental animals to capture the filthy remains that we have left to the Pacha [10]. The whales inscribe, within this exhibition project, the inherent inquiries of humans into the meaning of life and death through their passions, vices and hobbies. Moreover, these precursors coexist within the same neoliberal project and appear as fissures that have been assimilated through a wandering search for materiality and the organic nature or resources that the desert preserves, and that at the end of the day are strictly entangled in the extirpation that they have provoked upon much of its landscape.

The fieldwork by Lehman Brothers delves into the desert contours that are the vestiges and waste of extraction. In the face of the never-ending collapse of the global economic system, the group has explored more than one area where extraction can be seen in South American, including diving in the ocean, climbing through exploited hills, and traveling through sun-beaten trails. All these activities draw a few metaphors that reserve or protect an obsessive feeling, the monomania so characteristic of capitalism.

Here, the strategy for dialogue, within the framework that inscribes an exhibition, goes beyond capitalism, globalisation and the European chimera about decolonisation. We could further investigate the objectives of this exploration, however, Lehman Brothers have extended a collateral analysis on extractivism to other subjects and even objects that make up these ecosystems.

Finally, the locations and images that are part of this project are evidence of neoliberal globalization and its role in mining and whaling. A fact that brings me back to the words uttered by Moby-Dick’s narrator, Ishmael, who exclaimed: “It was the whiteness of the whale that above all things appalled me”.

*This essay is part of an initiative to foster Spanish and English Language critical writings from a range of new talents across the visual arts; and as a partnership between Rotunda in Santiago de Chile and SixtyEight Art Institute in Copenhagen, Denmark.

**A version of this essay was included in October 2020 in the exhibition catalog and anthology, Cerro Point Blanco by Lehman Brothers. Published by Really Simple Syndication Press in Copenhagen, Denmark.

Visit: www.rssprss.net to learn more about this publication.

[1] ¿Qué es el litio? (What is lithium?) Article on the Chilean Ministry of Mining website. Accessed on 10/09/2020: http://www.minmineria.gob.cl/%C2%BFque-es-el-litio

[2] See video of the project Pendulum Rising by Lehman Brothers: https://youtu.be/44fsbq8koIs

[3] Pendulum Rising -20.1524.15 – 69.479.65 (numbers are coordinates of this site-specific work). NaNO3 vs NH3 was the initial project subtitle – which served as a parallel juxtaposition of sodium nitrate (chilesalpeter) and ammonia with two pendulums turning clockwise and counterclockwise from tripod stands; and where two quotes by the Prussian philosopher Immanuel Kant “Der Raum ist kein empirischer Begriff” (Space is not an empirical Concept) and “Die Zeit is kein empirisch Begriff” (Time is not an empirical Concept) were written; one with ammonia and the other with sodium-nitrate.

[4] Valencia, Sayak, “Capitalismo Gore”. Cap. 2: Capitalismo como Cosntrucción Cultural (Tenerife: Editorial Melusina, 2010) p. 50.

[5] See publication of the exhibition El tráfico de la Tierra (Earth Traffic), a research project by photographers Xavier Rivas and Ignacio Acosta with the participation of art historian Louise Purbrick. More information at www.tracesofnitrate.org

[6] Canclini, Néstor García: La Globalización imaginada. Paidós Iberica: Barcelona, 2009.

[7] Boisier, Sergio, “Globalización, Geografía Política y Fronteras”, publicado en Revista Estudios Transfronterizos, Vol. I, Nº 1, INTE, Universidad Arturo Prat, Iquique, 2003, pp. 49-68.

[8] Demos, TJ. Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Berlin: Sternberg Press, 2016), p. 19.

[9] Note from the translator. “We choose to change the Spanish word of maritorio to the Latinized form of maritorium for two reasons. First, maritorio could be difficult to translate (i.e sea + territory; and second)… The idea of the Maritorium calls on researchers to overcome the dichotomous viewpoint between sea and land, between maritime and terrestrial environments. Without ignoring the heuristic potential of analyzing marine environments as distinct spaces from land, the reality is that within the maritorium subjects have a much more fluid and integrated relationship with the environments they occupy.” From: Jorge M. Herrera, Miguel Chapanoff. Regional Maritime Contexts and the Maritorium: A Latin American Perspective on Archaeological Land and Sea Integration. Published online: 27 November 2017 Springer Science, Business Media, LLC, part of Springer Nature 2017. (P.171-172).

[10] Aymara or Inca word which simultaneously means both time and space. Often translated as ‘World’, or may refer to the whole cosmos or to a specific moment in time; or to a ‘world-moment’ i.e. space-time. Here the author refers to the ‘bare life’ vulnerability given by the space and time continuum (i.e. of ‘Mother Earth’ and as a figure of speech).

Español

Español