The latest edition of La Biennale di Venezia is developed under the concept “May you live in interesting times”, an English expression for a supposed Chinese saying, where the irony of the curse is that from a historical perspective, the most interesting times are always catapulted by disorder and conflict.

Under contemporary circumstances, Olivia Berkowicz reflects on the obsession to predict the weather and the future, and how through this data collection a plague cloud- looms, which anticipates fascist times and an excessive simplification of reality leading us to this crisis in interesting times.-

By Olivia Berkowicz | Images courtesy La Biennale di Venezia – 58th International Art Exhibition

In 1884, the British art critic and social thinker John Ruskin presented a series of lectures at the London Institution entitled “The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth Century”. In this lecture series he draws on antique and pre-modern descriptions of clouds, in a search to analyse his growing sense of anxiety over the new weather conditions. At the end of the First Industrial Revolution, Ruskin was witnessing the ever-increasing coal-fueled smog which enveloped cities, villages and landscapes from industries pumping out new commodities. A “storm-cloud” was covering the sky and his beloved sun; a “plague-wind” bringing uncertain weather and bad tidings of battlefields and societal unrest. In a diary entry from July 1871, he wrote:

[…] the sky is covered with grey cloud; ⎼ not rain-cloud, but a dry black veil, which no ray of sunshine can pierce; partly diffused in mist, feeble mist, enough to make distant objects unintelligible, yet without any substance, or wreathing, or colour of its own… But I would give much, if I could be told where this bitter wind comes from, and what it is made of. [1]

Two decades later, the first iteration of the Venice Biennial of Art takes place to celebrate the reign of the monarchs. This imperialist endeavour aligned with what Amelia Jones terms “the midst of the heatedly romantic, simultaneously self-assured, and culturally anxious moment of mid-nineteenth century Europe,” where the rise of capitalist markets and cultural imperialism had already begun to alter the life of Ruskin and his contemporaries.[2] If only the fluctuating markets and climate could be analysed and controlled, their anxieties would be assuaged, right ?

In James Bridle’s book New Dark Age (2018) he charts the history of early computational thinking with the rise of meteorological prediction. The story begins in 1916 with mathematician Lewis Fry Richardson who devised the first weather forecast without a computer. Richardson believed that by collecting years and years of weather data from across the world, he would be able to forecast the weather. Dividing the world into a matrix of gridded squares and solving the atmospheric equations for each section, he was only lacking the technological prowess to realise his dream of predicting the future. His vision would only have to wait until 1947 before the American scientists Vladimir Zworykin and John von Neumann had the tools to implement computational power to predict the weather in real-time; this sentiment was echoed in their writings “All stable processes we shall predict. All unstable processes we shall control.”[3]

Collecting clouds at this year’s edition of the Venice Biennial is easy. Lara Favaretto’s misty air-humidifier gives some respite in the blistering sun outside the Central Pavilion at Giardini, deftly entitled Thinking Head, which is in good company with the French Pavilion and Laure Prouvost’s piece Deep See Blue Surrounding You.

The practice of forecasting the weather, signifies the success of computational thinking in 20th Century ideology. By amassing large amounts of data, one will hold the key to predicting the future in one’s hand. Seducing us with its power, apparent complexity, and final naturalisation – the cloud enters the stage as the form which more than anything else comes to represent the aesthetics of computational society.[4] A complete collapse of understanding ensues, where the century-long process of translating the world into data has rather than making it simpler to grasp, it has become so complex that we’re completely befuddled by it. The cloud stands in as the perfect metaphor for the Internet; a triple point leaky crystal, a fatal morgana on the horizon.[5] Collecting clouds at this year’s edition of the Venice Biennial is easy. Lara Favaretto’s misty air-humidifier gives some respite in the blistering sun outside the Central Pavilion at Giardini, deftly entitled Thinking Head, in good company with the French Pavilion and Laure Prouvost’s piece Deep See Blue Surrounding You. These clouds are ethereal puffs, lacking both substance and weight. They enact what the cloud has come to represent in late-capitalist society, the technological sublime which has become synonymous with what Bridle terms a new dark age; in the moment of complex decision-making, the brain chooses the least amount of exertion although knowing that decision to be faulty. Thinking Head becomes the ironic commentary on a society jacked up on Fitbits, apps and specs.

I turn away from the endless queue to enter the Nordic Pavilion instead. Weather Report: Forecasting the Future features the works of Ane Graff, Ingela Ihrman and nabbteeri who in a Harawayan vein speculate on fictive intra-species entanglements and toxic liaisons. From Ihrman’s neo-naivistic exploration of floral forms through sculpture, to Graff’s and nabbteeri’s techno-romantic installations, the sublimation of ecological trauma is disguised behind the auto-tuned narrative of nabbteeri’s video piece Blackout.

I turn away from the endless queue to enter the Nordic Pavilion instead. Weather Report: Forecasting the Future features the works of Ane Graff, Ingela Ihrman and nabbteeri who in a Harawayan vein speculate on fictive intra-species entanglements and toxic liaisons. From Ihrman’s neo-naivistic exploration of floral forms through sculpture, to Graff’s and nabbteeri’s techno-romantic installations, the sublimation of ecological trauma is disguised behind the auto-tuned narrative of nabbteeri’s video piece Blackout.

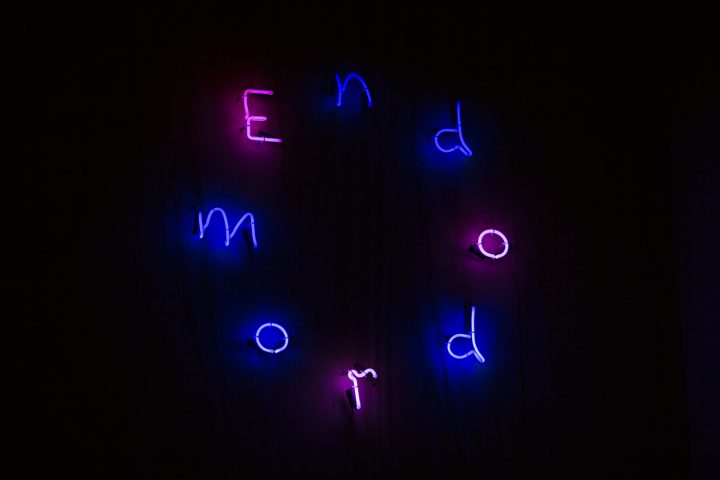

If the cloud had a voice, it would be the seductive non-characteristics of millennial whoops oversaturated with algorithmically controlled variances. The organic is just a mirage, lulling us into pleasant bursts of identification with nature robed in cuteness. At Arsenale, the hypnotic swirls and swivels of Dominique Gonzalez-Foerster’s Endodrome render the same illusory self-determination of the subject. One is herded into a darkened room where biennial staff fix VR-headgear on the visitors. The audience becomes the artist, where in the safe confines of Foerster’s cosmos, a vibrant Rorschach performance is played out with one’s gaze.

The organic is just a mirage, lulling us into pleasant bursts of identification with nature robed in cuteness.

Ultimately, the body is put to rest while the labouring gaze does the work. More successfully, the Danish Pavilion exhibits Larissa Sansour’s Heirloom. The town of Bethlehem becomes the site of an eco-disaster in the future, where the plot is driven by the dialogue of the founder of a subterranean orchard with her underground-born successor which is fated to return to the surface and repopulate. Themes of trauma and collective memory are explored, at times heavy-handedly in the film In Vitro, however the sculptural monument next door envelops the visitor in a dark milieu, where a crescent formed sliver of light escapes behind a large sphere.

Expounding on this theme, the Lithuanian artist Augustas Serapinas joins the performative and sculptural in Vygintas, Kirilas & Semionovos. A heap of grey bricks (safe for re-use) are haphazardly stacked on a platform of the same concrete material. Removed from the Ignalina Nuclear Power Plant, Serapinas invited children from the ‘atomgrad’ city Visaginas, whose family histories intertwine with the closure and subsequent cleaning up operation of the nuclear power plant, which after only three years in operation was closed due to the Chernobyl catastrophe. A sign of Soviet oppression and ecocidal waste management, Serapinas’ project points towards the breakdown of grand narratives of societal progress and how the modernist grid crumbles into the bodies of labourers and their children, ultimately to rearticulate a history of failure and trauma.

The Schauspiel of trauma is at its worst example in Christoph Büchel’s Barca Nostra. Situated across from the art world glitterati and their spritz’s, they go about their business across from a ship which sank carrying 800 migrants in its cargo. I’m not better myself, I find a spot in the sun and sink my teeth into a panini next to everyone else, overhearing plans for next years’ shows “Shall we exhibit so-and-so next November, you think?”. In the writer Sarra Anaya’s piece on the platform Kontext, she discusses the rise of nationalisms and fascisms in Europe in anticipation of the European Parliament elections.[6]

We live in interesting times, but interesting in the sense that the far-right is rising; micro-fascisms and over-simplifications of reality are increasingly gaining ground and the sense of a united leftist seawall against these forces is at best beginning to form.

We live in interesting times, but interesting in the sense that the far-right is rising; micro-fascisms and over-simplifications of reality are increasingly gaining ground and the sense of a united leftist seawall against these forces is at best beginning to form. In her article, Anaya brings up an advert commissioned by the European Parliament in which we see a, more or less, ethnically white French village, where a storm cloud rises on the horizon. Black, sticky, tentacular – it rains black blobs onto people, books, computers and instruments, metaphorically silencing the right to expression and the freedom of the press. It ends in a triumphant scene where the inhabitants propagate culture despite the dark forces without. The cloud clears away and the sun re-enters the stage. Ruskin rejoices. Dramaturgy reversed, the Lithuanian pavilion stages Sun and Sea (Marina) by Rugilė Barzdžiukaitė, Vaiva Grainytė and Lina Lapelytė. The plague-cloud enters the operatic towards the end, echoing Ruskin’s fears of a sun clouded behind a dark veil. Except that today, the plague-cloud takes the form of a translucent mist, invisible to the naked eye; microplastics, algae, pollution and radiation are its main protagonists.

The plague-cloud enters the operatic towards the end, echoing Ruskin’s fears of a sun clouded behind a dark veil. Except that today, the plague cloud takes the form of a translucent mist, invisible to the naked eye; microplastics, algae, pollution and radiation are its main protagonists.

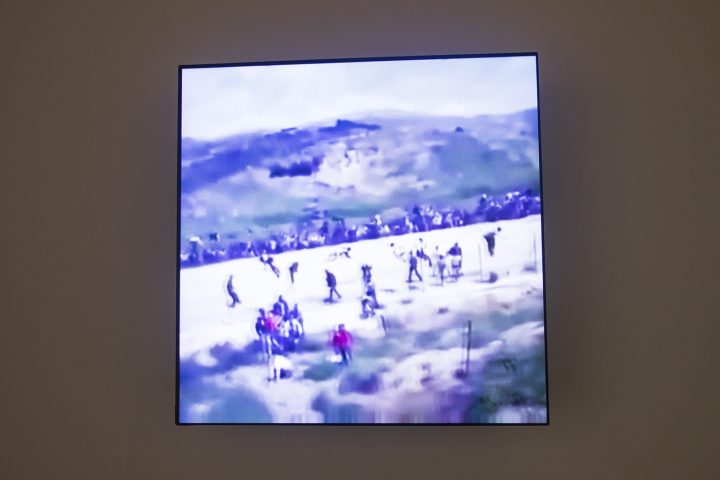

Once the grid of weather forecasting has become embedded into our own bodies, and the collection of data is at constant work, the intimate body has become the site for what Paul B. Preciado terms the “pharmacopornographic”. In Taiwan’s pavilion, Shu Lea Cheang departs from the architecture of the panopticon as the main tenet in their installation 3x3x6; the standardized size of industrial imprisonment today. In one of the rooms, ten narratives unfold across monitors on the floor, recounting historical instances of disciplinary and carceral actions against queer, black, trans and other non-heteronormative bodies. Neïl Beloufa and Lawrence Abu Hamdan present works which both deal with the disclosure of the militarization of space across bodies. Beloufa’s We only get the love we think we deserve. where the visitor is invited to join a video-apparatus which only activates when one’s head pushes up against a mask with two slits. Ex-soldiers recount their experiences in a one-to-one headlock. Hamdan contributes to the Arsenale with This whole time there were no land mines, eight video loops on square screens where found footage from 2011 shows The Golan Heights – a piece of land annexed from Syria by Israel. Interested in the militarization and politics of sound, Hamdan here investigates ‘the shouting valley’ – a place where the topography enables an acoustic leak across the border.

An archival impulse, Chile’s Voluspa Jarpa makes a grand attempt in her Altered Views, presenting a museum of hegemony, of male dominance, racism, colonial infrastructures and economic forces.The rooms she occupies are dizzyingly dense, incorporating video, opera, peeping holes, objects and drawings. A Foucauldian investigation of biopolitical governance, she points towards the force in dissecting epistemes which organise and exploit the colonised, exploited and disenfranchised bodies.

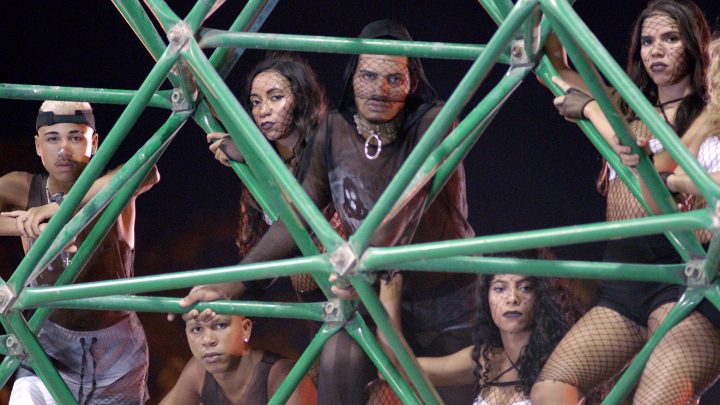

In a public seminar at the Public Art Agency in Stockholm, the comparative literary professor Emily Apter recently spoke about micropolitics through the glossary of Félix Guattari and affect theorists Laurent Berlant and Kathleen Stewart, amongst others. Life itself has become the site of infra-political forces, where moods and affects have become as ubiquitous and powerful as the weather itself. A storm of click-bait and alt-right trolls may have unprecedented impact on daily events, the ripple effect now staged across the kaleidoscopic surfaces that constitute our digital climate. The Brazilian Pavilion features Bárbara Wagner & Benjamin de Burca’s two-screen video installation Swinguerra, which shows the powerful choreographies of grass-root dance schools from the Recife suburbs. Swingueira merges with the Portuguese word for war, presenting a battlecry for the black and non-binary bodies on the screen. In these times of increased trans- and homophobia, the choreography becomes a gauntlet thrown in the face of Bolsonarian politics.

Echoing this call to arms of visual activism, Zanele Muholi’s project Somnyama Ngonyama, Hail the Dark Lioness will with time create 365 self-portraits of a black lesbian in South Africa.

The first day of the performance program was cancelled due to torrential rain. The London-based artist Victoria Sin was back on stage on the second day where they performed together with Matteo Gemolo (traverso) If I had the words to tell you we wouldn’t be here now. Their face beat, body cinched for the gods, stripper-heels on – they lipsynched their way through a tender drag performance exploring the limits of identity and understanding through language. Using the aesthetics of camp storytelling, Sin points towards the violence in naming, playfully exploring how the taxonomisation of things restrict and control the experience of the environment. In the interstices between cognisance and non-cognisance, Sin’s performance offers a powerful riposte to Zworykin and Neumann’s positivist mantra of control and prediction.

In the sunshine of the Giardini, a plague-cloud looms on the horizon no longer anchored to the island Poveglia where the plague-ridden once were quarantined. Staring ourselves blind at some point fixed far away, voices from the lagoon whisper in your ear: we’re already here.

[1] James Bridle, New Dark Age (London: Verso, 2018), 17.

[2] Amelia Jones, “‘Every Man Knows Where and How Beauty Gives Him Pleasure’. Beauty Discourse and the Logic of Aesthetics”, in The Art of Art History: A Critical Anthology , edited by Donald Preziosi (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2009), 375.

[3] Bridle, New Dark Age , 26.

[4] Ibid., 7.

[5] Marianna Feher, “Notes on Combating Operational Desires”, in Supramen, 2018.

[6] Sarra Anaya, “Europeisk kultur = joddling, bratwurst och demokrati?” Kontext Press , May 30, 2019, access: https://www.kontextpress.se/kultur/europeisk-kultur-och-fascism .

Español

Español