The balance between the abundance of images and poetics that can reconstruct their meanings is what the Chilean artist based in Brussels and Paris looks for through his works and films, which have been his way of telling unspoken stories. A disappointed of the image that still believes in art as persistence and resistance.

By Carolina Martínez | Images and films (trailers) courtesy of the artist | Photography: Felipe Ugalde

Carolina Martínez: Tell me where you come from. In what context did you grow up and what were the first artistic references and influences exogenous to that world?

Enrique Ramírez: My father builds boat sails; my mother is a medical technologist, specifically dedicated to the Pap test. So on my dad’s side, I was born observing the investigation of the material and navigation and on my mom’s side always looking at the tiny, visible only under the microscope: galaxies and landscapes that are actually human bodies. Then I studied music for around 5 years while I was in school, but at one point I decided to stop because I felt it wasn’t my thing. I don’t know why I thought that, but I decided I would do something else. It was then that I decided to study cinema, not only because I wanted to “make cinema”, but because it encompasses many things that interested me: sound, image and “travel”, as well as writing and photography.

I began to study Audiovisual Communication with specialization in Cinema at the Arcos Institute, discovering that world through montages that I made for my friends, so my first jobs were as a documentary filmmaker and that was my profession for a long time. Later, I met Néstor Olhagaray and Guillermo Cifuentes, who opened to me the window to the art world, in which my first references were Alicia Vega (I worked in her film workshop when I was still at school) and Eduardo Vilches, who was his husband. Later, references from the cinema world began to appear, such as Raúl Ruiz or Wim Wenders. And the impression of when I saw and knew Eugenio Dittborn’s airmail paintings.

And so, without even wanting to start artistic practice, I began intuitively relating to my video productions, without knowing much where they were going. But I did know that for me it was a way of telling things that I couldn’t talk directly. That is why for me cinema is something so important: it is my platform to tell stories, or rather, to ask questions before anything else.

CM: You lived some years of the dictatorship. What are the memories that come to you when I tell you this? How is that imagery like in relation to the shared imagery, and this in relation to the one that exists outside of Chile regarding this dark period?

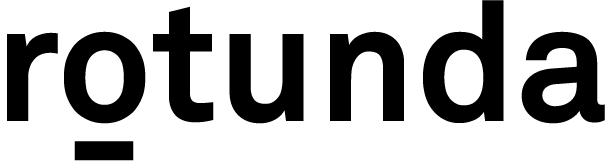

ER: I go back to what I was saying about the video: it is a medium that helped me to tell a lot about it, as in “Brisas” (Breezes), a sequence-shot with a character walking whose voice-over is my memory. I also think of the many similarities with what happened recently in Chile. I remember the cacerolazos (barrage of pots-and-pans bangs as a sign of protest), the blackouts, and the military in the streets. I also remember planes and helicopters because I lived in La Cisterna near El Bosque airbase. But the truth is that it is something that now I see it blurred. I lived that until 11 years old, so for me all that was normal. I saw the real change when the dictatorship ended and democracy came again. That was when my generation and I realized what was happening and we did not know.

All that time I lived quite protected, especially by my mom, who used to go out from home very early, and my dad worked at home, so we didn’t need to go out much. I think again about that cloudiness of memories in “Brisas”, and I think are the same feelings that my friends have: the impression that people disappeared, not knowing if it was due to moving or another reason. Situations with no explanations.

“Whenever I thought of Chile, I thought of a slightly gray Santiago. A gray that comes from that hidden story. A gray that I see a little dark blue. I could say that I see Santiago in one color. Also wet and cold, which has been translated in a way of seeing and filming”.

CM: When you decided to study cinema, how much did your own and collective imagery influence?

ER: No doubt, all those memories influenced. But also the cinema and the arts: in general the time in which I was born, everything that we saw; a visual and sound impact that I think will influence me forever. It is not very easy to leave behind all that.

Whenever I thought of Chile, I thought of a slightly gray Santiago. A gray that comes from that hidden story. A gray that I see a little dark blue. I could say that I see Santiago in one color. Also wet and cold, which has been translated in a way of seeing and filming.

CM: Have you ever wanted to make movies or did you always have the premise of developing in the field of visual and / or media arts?

ER: Not really. I’ve had proposals to made long-length films and other projects in that regard, but it is something I’m not interested in. Cinema was a tool for me. Nor was I very interested in showing my shorts at festivals, for example. I am not “very much in the world of cinema”, I am inside because of my relationship with documentary work and that is the methodology that I learned and that I use to work. I’m always a little bit outside.

CM: How did you get to Le Fresnoy? How was that experience and how did it influence aesthetically?

ER: The opportunity came thanks to Néstor Olhagaray, I owe him a large part of my career. I was awarded at the Biennial of Video and New Media (now Biennial of Media Arts of Chile) to go for 3 months in 2006 to Le Fresnoy, France, within the context of a residency.

The following year I decided to apply as a student and I was accepted. It influenced too much because I came from a world with a lack of everything and when I got there I found totally something else. At first, that was complicated, everything was pseudo-professionalism. On the other hand, I would say that I am too grateful to have learned to make movies in Chile because I have the impression that I was able to take advantage of what I had there much more, knowing that lack that I mentioned. Le Fresnoy undoubtedly opened many doors for me, starting with the collecting world, and it was thanks to that world that I was able to continue studying: I sold my first video made there, and thanks to that sale I was able to continue studying the following year. Later, I learned another language, made friends that I have until today, in addition to opening myself to other possibilities of projects, residencies, and trips. He took me to festivals, I met with Bill Viola, I met Jean Luc Godard and Raú Ruiz. All those references that you see from afar, I was able to do it thanks to being in Le Fresnoy; many people come despite being small.

Aesthetically it influences you a lot, it is said that there is a “Le Fresnoy” style. The truth is that I do not think I have that “style” much, but there are some who say yes. It happens that even on a plastic level it influences. For example, in one of my last exhibitions, I needed 20 old monitors that they got, something that I probably would not have achieved without their help.

I have developed a long relationship, from student to jury and almost all my post-production processes are made there.

“When I left I did not think of that or with that ambition. Yes, it is true that many times we have to turn ourselves invisible in the local context so that they “see” you. The fact of validating elsewhere seems to automatically validate you in Chile, which is very unfair. But it’s still a way”.

CM: Do you think that leaving the country is one of the ways to develop internationally?

ER: When I left I did not think of that or with that ambition. Yes, it is true that many times we have to turn ourselves invisible in the local context so that they “see” you. The fact of validating elsewhere seems to automatically validate you in Chile, which is very unfair. But it’s still a way, I don’t know if it’s the only one. I know artists who have developed their careers in Chile, I guess are elections. In France, there are more options, but I also have many artist friends who have not been able to make their careers there either. I agree that staying in the country can get it harder, the number of possibilities is less due to several factors: there are too many art schools, there is no collecting and the State hardly buys works. But all this also helps that artists ask themselves again: what is art for?

I had to leave, but it was not something conscious, or I do not know if it is so necessary. There are other things: a much more collaborative work, an issue that I think has been lost in general in the art world, but in Chile, as a result of these shortcomings, people help each other and it is a very important and beautiful weapon.

CM: The image as a vehicle of itself or as a representation is something that differs a lot between cinema and what can be in art or film-essay, a feature that is sometimes seen in your pieces. How would you describe that image captured through your work and visuality?

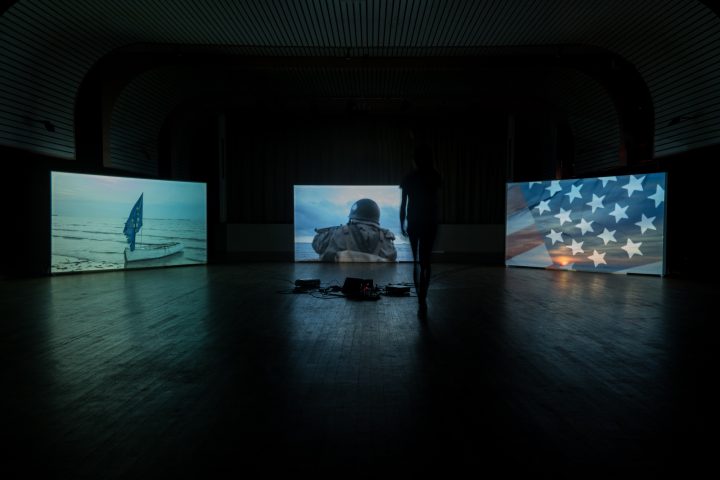

ER: For me, images are tools, they are questions that travel tied to images. If I had to draw it, it would be a stone hanging on a thread with a question mark. By this, I mean that they have a weight and that they also carry a hidden burden along with that question, which is a window that we can decide to open or not. The art that interests me is the art that asks questions, art cannot give answers. And in this interrogative proposal, the viewer has a very important role, which is why I try to be super aware of that: an artist generally creates to show, thus making the viewer part of the work. When I make a piece, it does not only mean making that video, but it also involves how that video is installed, what facilities or difficulties it gives to the viewer so that they can face that image and that question, which is the window that one opens and what I will not answer.

“The art that interests me is the art that asks questions, art cannot give answers. And in this interrogative proposal, the viewer has a very important role, which is why I try to be super aware of that”.

CM: At what point do you think an artwork is resolved?

ER: I have artworks that I do consider to be well resolved, but it is relative anyway, each work has a life, which is not perfect, because if it were, I would have nothing else to do, just retire.

It is clear that, in addition, the works have a margin of error and imperfection that is something that I also look for. And the idea of that “methodology” is that when I film I never know what the end will be: that margin is part of that almost perfection that I seek. I need not knowing if things going to result, in order to feel they have a certain soul and life, something that you can almost feel or touch it.

CM: So, It is clear to me that part of your methodology is to feel that degree of uncertainty, that hidden potentiality. But in your work, is a problematic your starting point? Or first, do you see an image and then you link it with that theme?

ER: In general, I’m like an image searcher. I would say that I am a disappointed by the image. We live in a world that is full of them, so it is very difficult for me to find them, and the truth is that I find the most impressive ones in the press, I see many newspapers, which are usually my starting point, what is happening in the world at the moment. So much of my methodology is like that of the documentary filmmaker. For “Los durmientes” (the title, in Spanish, means both sleepers and railway ties), which has to do with the thrown persons into the sea in Operación Cóndor, I interviewed different people, including relatives of disappeared detainees. If I cannot find the information in the press, I do it through the interview, in a word from someone, or in several sentences from different people, and that is what can make sense to me. And this is how I try to invent images; from my imagery, from what interests me in my way of seeing, but also that of others. The newspapers and the context are very important to me; the world and its conflicts. And that is the world that interests me, the one that is often linked to the sea by my father’s work building sailing sails, which seem to me a symbol of freedom and an invitation to get lost, a sign that the starting point or the goal is not the most important thing, but that insecure, unknown, uncertain journey, which is what the sail inspires to me. I seek those uncertainties.

“If I cannot find the information in the press, I do it through the interview, in a word from someone, or in several sentences from different people, and that is what can make sense to me. And this is how I try to invent images; from my imagery, from what interests me in my way of seeing, but also that of others”.

CM: The image as abstraction and also as a negation of other multiple possibilities that potentially live within the chosen image. Possibility, denial and decision: How does that system live within your images that has to do with the world of cinema, editing and documentary?

ER: Some days ago I was thinking about a transparent image, about how it would be an image that is cannot be seen. But if we were transparent and could see the lungs, the blood, etc., perhaps we could not bear to see ourselves, because we could see much more than we really need to see. It would be an image that eats itself. Raúl Ruiz used to talk about the danger of the transparency of the human being because we could see much more than we need. And it is there where I think of the images of cinema, photography, and painting. But especially in that image of the cinema, where the idea of the backroom lives, of what we do not see in that image, what is left out.

When I think of an image, many times I think of that transparency and that backroom. An artwork of the Pacific, a still image of the sea moving at night, which does not even have sound. I have seen people sitting for hours in front of that image thinking “I am sure those bodies were taken by the sea”; others thinking that the disappeared detainees were thrown into containers. What inspires you that image depends on the context of where you come from and that is the everything invisible. That is where the importance of the viewer lies: what you give them to complete the image and what that can say about a person. The backroom is something that interests me a lot and in that sense, I think of the phrase of Ansel Adams taken by Alfredo Jaar: “a photograph is not taken, it is made”.

I remember a project I did in Norway, “INcoming”, which comes directly from a newspaper (I collect them) from 2016 with the image of the Minister of Immigration jumping to the sea in the Syrian coast in an orange suit -something very ridiculous- for demonstrating that she could feel in the way that an immigrant does at sea. They saved her in 2 minutes of course. I reconstructed that image with a Syrian immigrant off the coast of Norway, in the North Sea, with a similar outfit. Something that can be a very simple exercise, but for me, it was very important to return that image, like that phrase by Juan Castillo “I give you back your image”.

Those images that one invents, you also invent with the viewer. In almost all my films, the backroom is something that is always present, and there is also some fiction, which can make you feel that something is not real, but to take you to your own construction: how you turn it into something real. I cannot know what the other is thinking.

CM: As a symbolic container I see the landscape, but one that makes me look from the top down, or in the opposite direction. But what I mean is the inclination: to the sky or to the ocean. Why them?

ER: The sky has to do with my mother, those testing I told you about, which are like landscapes in the sky. And that is where the interest comes from, and that in the end is also a seascape. But everything brings me a little to the maritime and aquatic issue: we grow inside the womb; life, death. And also to the issue of instability and itinerary. Time is something that is also important in my work: when we are faced with an image, how much time does an artist ask a viewer? How much time are you willing to spend in front of that image? Time has to do with the landscape, how we look at things that change. For example, “Océano” is a sequence-shot between Valparaíso and Dunkerque, in the north of France, with 25 days that to anyone might seem the same, but they are very different. In this way, there is also the idea of the unstable, what moves and that is how I conceive life. You are never sure and art cannot give you certainties either.

“I have that kind of image disappointment, I make fewer and fewer images. It is very difficult for me to find something that surprises me, rather what surprises me is human misery and that is not the images that I want to create. My head is left looking for the balance between the information and a certain poetic. We live in a world with very little poetry and too many images, and what poetry can achieve is to rebuild the violence of those images”.

I have that kind of image disappointment, I make fewer and fewer images. It is very difficult for me to find something that surprises me, rather what surprises me is human misery and that is not the images that I want to create. My head is left looking for the balance between the information and a certain poetic. We live in a world with very little poetry and too many images, and what poetry can achieve is to rebuild the violence of those images. For example, how many images do you see now of immigrants drowning into the sea, on the beach floating without anyone being surprised? That is when poetry resignifies the load of the image and you can find images that have that poetic load, but with the information contained and the one that is not far from the world.

CM: These images also have to do with it, but more than ever, it makes sense to me that you deal with the issue of immigration. I think of the year we are in, and of the collapse in many ways, where the limits and borders should be increasingly diluted, giving way to solidarity and collectivity that could cushion us as humankind. But it is totally the opposite, a Europe for example, and also where you live, which seemed to be a paradise that wanted to equate economies and conditions, that it loomed as a hope, but that today is nothing more than a paradise for right wings, in ideological and economic terms. It is a bit gigantic to cover this in a question and in life, but what is your diagnosis or perspective of what has been happening more notoriously since perhaps the late 90’s?

ER: Intellectually I feel very pessimistic about the future, which does not mean that I do not have hopes that there are things that can change, and our closest example is everything that has been happening in Chile. On the one hand, I have very little hope that something will really change, I see it in my mother, for example, who is 81 years old and still thinks of working because she needs it … and that is not the story of my mother, it is the story of many mothers. It is there that I think that art is important because it is an instrument of persistence of ideas, so I feel lucky to be artist and I give to myself energy since art is one of the few things that is still free and capable of having an independent reasoning, something that we have to keep taking care. It makes me want to keep doing things. But I am very pessimistic about how the world is, people don’t believe in anything anymore, nobody knows what can sustain them on this earth. In my case, being an artist has a responsibility and that is what drives me to do things, to keep moving forward and looking for images. It is an act of persistence (and resistance) that creates noise little by little.

CM: This ending of solidarity in the world, in society, and especially in the working force, it has provoked the near victory of neoliberalism without almost giving any battle. But the situation was enough exhausting and what we have been living in different parts of the world is that, as Gastón Soublette mentioned, humankind simply got tired of the inheritance of industrial society, and what has happened in Chile is simply one of those explosions, which are not known where and when they will explode. How has this impacted you and how do you think it will shape (or not) your practice? Do you feel that as someone who is showing an image of and to the world, you must take a political position from your aesthetics? How do you configure this dialectic?

ER: The first thing I think about is that when I was recently in Chile, as soon as I arrived I started filming and recording a lot, but probably it will be a material that I will never use because it has been too much seen in the media. I register with my camera because it is what I do, it is what I learned from the documentary and perhaps after a long time, I will find in those thousands of images one that works for me.

Certainly, what has been happening will influence all artists, no one can escape. But it does not mean that it has to be translated into artwork, it is very soon to make works at this time around it. There is a whole intellectual issue that will take much longer to understand. I honestly understand that to some extent. I feel almost like a foreigner looking at everything that has happened. But I want to make it clear that it is good, independent of any kind of violence. But where are we going to get with all this? It is a question that perhaps I as an artist would have to answer first and then try to do something, regardless of whether my work is already a question. But I see that society almost forces artists to respond in some way and I don’t feel capable of responding to this, it has to pass a good time to take distance. It will take time to see what all that means, but I do feel that we are a more Latin American country. This tiger with kitty paws.

“Being an artist has a responsibility and that is what drives me to do things, to keep moving forward and looking for images. It is an act of persistence (and resistance) that creates noise little by little”.

CM: Do you think an answer – that society seems to be demanding it again – is necessary from artists to the world health crisis we are experiencing? I see it more as a rethinking of the art system. And without any doubt about the system under which the whole world works.

ER: Every change is tied to a possibility. So yes, I think there will be changes: what we are living we would not have imagined even in the worst American film. But continuing in the sense of what I mentioned before, we will have to wait again to understand all this that we live. As many say: the end of the world we knew and the beginning of a new world. It seems a bit far-fetched, but I don’t think the world just goes on as before. I don’t think so, but there’s nothing left to do but wait.

CM: How do you imagine or glimpse the image of today’s world?

ER: I would return to the idea of that transparent image, because we all want to look at each other, even between strangers. But we also don’t want to see as much as I already said. This can have very good things, like the idea of looking into each other’s eyes when we talk between us, but it also has that part so transparent, that I don’t know if I want to see it, maybe I would have to stop of looking at this image to not continue seeing this world with all those images and transparent walls. We would start to see the shit in the world and it would be unbearable. There are many people who do not want to see. This image also has to do with the imaginary of many. How is that image transparent? I have no idea, but it’s a starting point

CM: What projects and upcoming exhibitions do you have and how has your calendar been changing with the pandemic?

ER: At the moment I am preparing an exhibition for August at the Cultural Centre of Spain in Santiago, which for now we do not know if we will do it and I prepare my exhibition at the Centre Pompidou for the nomination for the Marcel Duchamp Prix in October, everything else is canceled until new notification.

Español

Español