By Rodolfo andaur | Images courtesy of the artist and Carlos Silva

There is no doubt that the landscape and its unique features have changed remarkably. Therefore, when observing the effects that physical and natural phenomena have produced, we create judgments, from rational thinking to its revelations that define it as such.

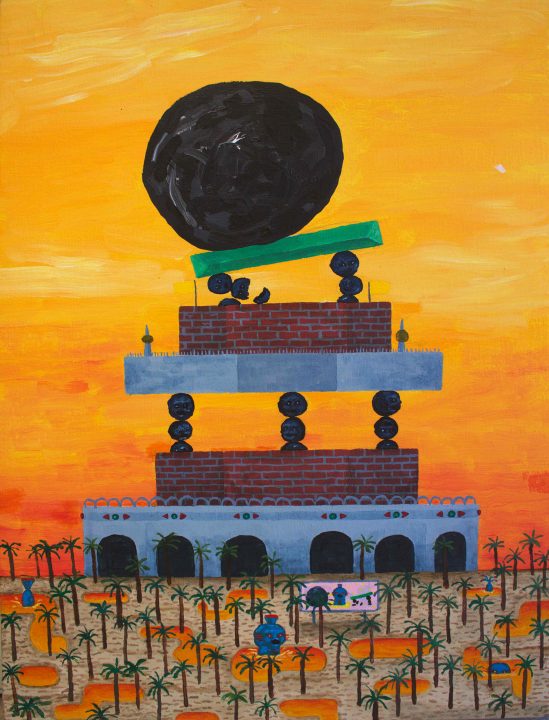

Today, we can confirm the existence of many writings that involve the interstices caused by the dominance of dress created by humans over nature. A situation that has brought new imaginaries to the fore, which, for example, contemporary art has recently been revealing. These issues have been studied by the visual artist Camilo Ortega who analyses, specifically, the origins of over-industrialization in the Tarapaca region. Given these characteristics, he has designed irreverent graphics within a global socio-political contingency conflicted by the Anthropocene.

In this sense, and taking as a basis the difficulties that appear when representing, from art, the reality of a landscape in crisis, we ask ourselves: What is the Anthropocene? [1] To this, we might add what the writer T.J. Demos has questioned: How does this new era work? Does its discursive framework relate to image technologies, including photographic, video-based, satellital images, those delivered and scattered through the web? How is this thesis of the Anthropocene? Because it remains, for now, a proposal that demands critical evidence, supported or refuted by different kinds of visualisation, and how could artistic-activist practices not only confirm but also provide compelling alternatives to adopt its rhetoric? [2]

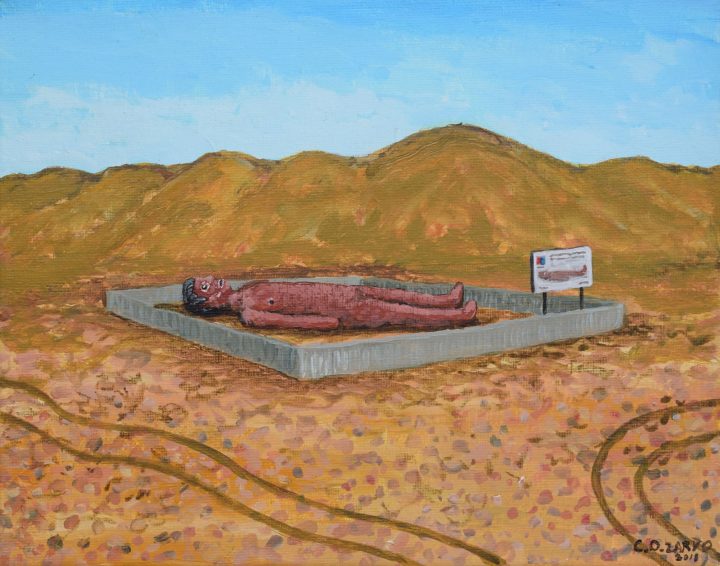

Undoubtedly, the Anthropocene inscribes, from a conceptual logic, a profile that deepens into the conflictive frames that some environments in this region have. This critical profile leaves far behind those artistic ideas that have only shown the naturalistic beauty of the desert and that have strictly omitted the visible deformations caused by the indiscriminate extraction of its minerals. Well, by dispensing with that substantivity of the desert we are denying a variety of feelings and perceptions that reduce its stamp to the postal format. A postcard eaten away by neoliberal logic that uses this landscape as an endless consumer item.

With this reading based on the Tarapaca landscape, the artist’s exhibition proposal, entitled “Land of Champions”, raises a series of questions that from new material forms perform the cosmogony of that inert, marginal and parched mood of the desert intending to synchronize a new epistemological perspective.

So through these pictorial, installation and illustrative marks, we glimpse other physical and abstract antecedents that have marked the historical vicissitudes of the landscape and its evolution, since we have been involved with a sensitivity associated with what exists, what is represented and, by the way, to the symbolic and the symbolizations of this same desert. Thus, by proposing a vision that goes against the well-known pristine nineteenth-century portraits, this artist stresses a series of images that have been fed with the huge changes that the landscape of Tarapaca has suffered. Besides, according to the scheme that street work gives off, this artifice has perpetrated in his works the conjunction of plastic with objects that twist the practice of an art shaken by its representation. This is the case of the calamorros that were used by the workers in different areas of the Tamarugal pampas. These boots, half-round, protected against the gravel and the rough terrain of Calico. Its functionality has inscribed a seal both from the patrimonial point of view and for the devices currently designed by cultural tourism. The calamorro as an object has impacted the practice of this artist. The arrangement in the exhibition space is a good example to see how Ortega questions the function and the original use of an object, and then sniffs in its current context to, finally, surround it with a new imaginary. The calamarros are, within this proposal, mere museum landmarks that appear deteriorated by the meaning that surrounds their memories. Therefore re-assigning them another functionality dislocates their true role.

Camilo Ortega has created sceptical scenographies that are explorations that hold off the environment and feel of the pampas and, mainly, the humanity of the region. He has justified this characteristic through a methodical review of documents, posters, and photographs from the early twentieth century. By the way, an action that has led to the collection of a countless number of symbols that industrialisation, capitalism and globalisation have forced us to face. It is necessary to highlight that many of these symbols have appeared in the traditions that externalize the human experiences that, under the complex productive scenario of this area of Chile, thrill through what reveals their own identity.

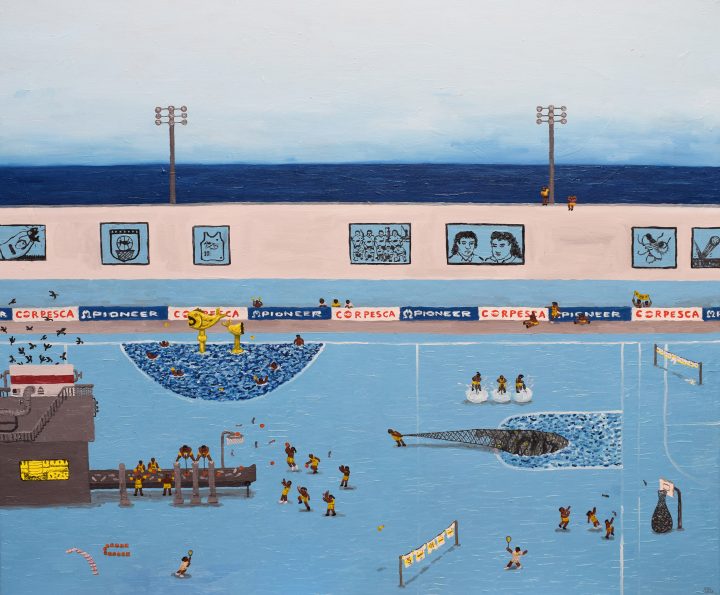

Given these antecedents, the look that we have assigned to the desert will also continue changing from those same community operations, many of which used sport as a synonym for emotional stability in the face of the untidy grievances suffered – and keep suffering – by the workers from hands of their employers and landlords. Within these communions, many of which are also defined as unionisations, the image of the silenced bodies removed from their desires for justice and dignity has been mitigated.

On the other hand, the evidence that justifies the staging of “Land of Champions” insert, from the colonisation-sport binomial, a series of disturbing visualities that coexist with countless social aspects that industrialisation has knotted, specifically, in the city of Iquique. As the sociologist Bernardo Guerrero has stated: “We have the idea that a large part of the local identity of Iquique is woven around the massive practice of sport. A practice that, among other things, is not about sport itself, but has much broader social consequences, which must be analysed within the framework of the demographic structure and economic growth achieved by the city of Iquique.”[3] Moreover, “… sports practice has burdened with various insignia since the world of sport is not only for those who practice it but also for all those who are around it, that is, merchants, spectators, commentators, authorities, etc.” [4]

In this way, this artist influenced by the slogan “land of champions”, has designed a reflective space on the landscape that surrounds Iquique. These landscapes have been violated and show a dichotomous reality that is still unknown. That is why through these pictorial and installation actions a natural need emerges to interrogate, connect, and even observe the desert from transdisciplinary chimeras.

The whole logos that I narrated above shapes, in part, the dilemmas that “Land of Champions” has, and that in the face of the artist’s praxis we could infer the desire to experience this territoriality in order to understand the cosmologies that inhabit our vulnerable geographies. At the same time, this exposure goes on to structure a narrative subjectivised by a visual culture that from a contemplative and analytical approach presents the landscape as an object of nature, a nature subject to the Anthropocene.

Finally, the imaginary of this artist highlights those aesthetics that, resected by daily life, are intercepted by the yoke of sport. From that dialectic, certain components come into action that declaim pissed off verses before the irruption of objects and subjects that continue (in) visible in different points of the Tarapacá desert.

[1] Scientists still do not confirm the name of the epoch that comes after the Holocene. However, a series of meetings have already been organised, for example, Welcome to Anthropocene that took place in London in 2016 http://www.anthropocene.info/

[2] DEMOS T. J. Against the Anthropocene: Visual Culture and Environment Today (Berlín: Sternberg Press, 2017), p. 9.

[3] GUERRERO, Bernardo El libro de los campeones: deporte e identidad cultural en Iquique. Chapter I – Deporte e Identidad Cultural (Iquique: Ediciones El Jote Errante, 1992), p. 11.

[4] Ibid.

Español

Español