“The criterion for survival is to succeed as a neighbor.”

– Torsten Hägerstrand

By Ana Rosa Ibáñez

Europe is in the middle of fall, but art is far from waning. On this occasion, part of the artistic community gathered at the very edge of the continent in order to bear witness to the work of artists from all over the world, concentrated at one of the world’s most relevant historical and political capitals, a place that has played a key role in the development of both Eastern and Western civilizations: Istanbul, where the inauguration of its 15th Art Biennial is taking place. Located on the border between Asia and Europe, from where it plays a part in both continents, and having been –up to this very day— an epicenter for multiple invasions, migrations, and renovations, the city offers itself as a fertile ground upon which to exchange perspectives on political and social issues.

Given the current political state of the countries belonging to the Mediterranean area, the recent Turkish attempted coup d’état, the country’s proximity to Syria, and the world’s political scenario during the year 2017 –and so on—, it’s not surprising that we as attendees were expecting the event to lean towards political pessimism and social drama. At least, this is what the Biennial’s name suggested. The curator duo Elmgreen & Dragset –who have been developing projects in this capital city for over 15 years— spent the past two years developing the concept of “good neighbour”, which was defined before the storms caused by Brexit, Syria, Palestine, Trump, and let’s sob. 56 artists from 32 different countries were invited to participate, bringing together enough material to densify their works and show us the darkest side of humankind. As spectators, we were prepared to look towards the future with terror, yet from the very beginning, we were invited to live the experience from a different place. During the press conference, the Biennial’s director Bige Örer assured us:

“This period of preparation for the 15th Istanbul Biennial has reminded us that, in this tumultuous time we are going through, one of the things that we miss the most is living together without having to abstain from our identities.”

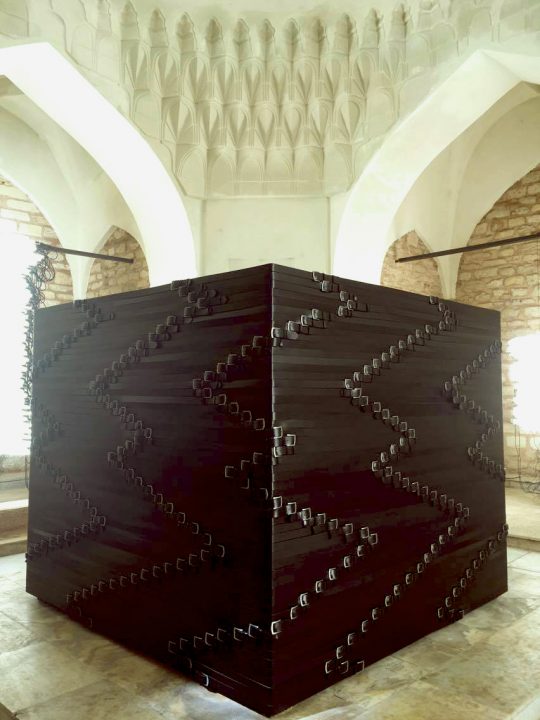

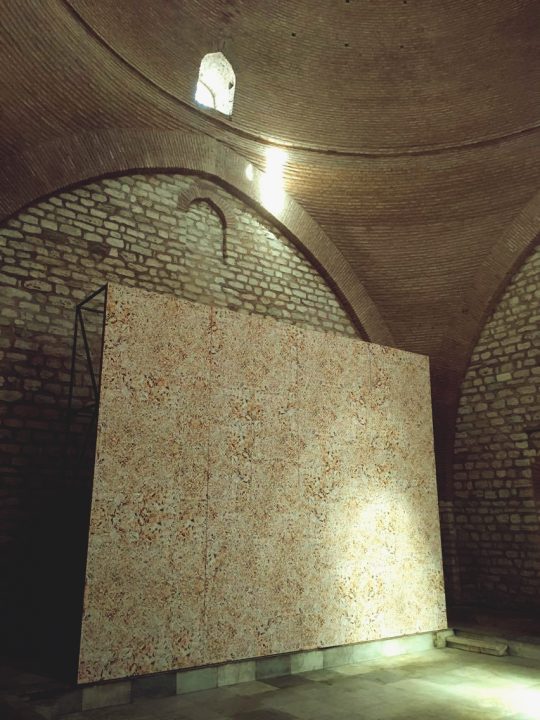

The Biennial was spread throughout different sites located within Istanbul’s Galata neighborhood, historically one of Western’s civilization’s most important centers for monetary exchange, having declared itself independent from ancient Constantinople’s predominant Islam faith from its very beginnings. From then on and up until this day, this area has upheld itself as an economic and cultural center, opening up to tourism and the market, as well as to diplomatic, educational and cultural institutions. The event was concentrated at the Galata Greek Primary School –a recurring venue for the Istanbul Biennial—, a place dedicated to learning and knowledge that closed its doors to students in the year 2007 due to a decrease in Istanbul’s Greek population during the second half of the twentieth century; Istanbul Modern, a former cargo warehouse that was transformed into an international modern art museum, designed by architect Sedad Hakkı Eldem in 1958; the Pera Museum, originally built as Hotel Bristol by Achille Manoussos in 1893 and turned into a museum after the building was renovated in 2005; ARK Kültür, a residential house in the Galata neighborhood, which was remodeled in Bauhaus style by its owner, Gülfem Köseoglu, in 2008, and opened as a space for culture and exhibitions; Yogunluk Atelier, where a group of local artists redesigned the space of an apartment in the Galata neighborhood for the event; and Kücük Mustafa Pasa Hammam, the only venue located further away from Galata, a disused Turkish bath built in 1447, which is recognized as one of the oldest in the city and reflects some of the key traditional characteristics of the Ottoman Empire’s social structures.

The different venues were already offering diverse approaches to the city’s history, their various forms of architecture touching on some nuances of the identity and transformation that characterize it. These are spaces that, at times, may have even transmitted notions of hegemony, differentiation, privilege and discrimination.

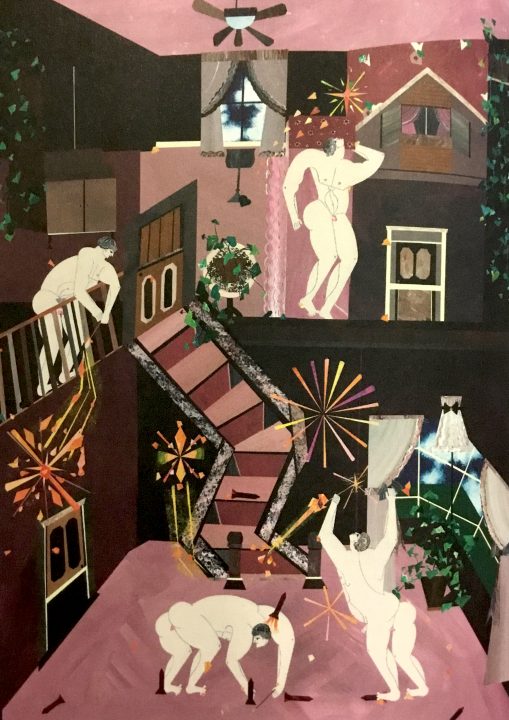

Much to the contrary of what was expected (which, by the way, is what should happen in a successful exhibition), delving into this show wasn’t at all about travelling to the future, but rather, about a journey into the past. The intense two years that the curators and artists spent working disgorged into an examination of personal memories, an analysis of the participants’ stories and childhoods that at times bordered on psychoanalysis. Of course, more than just a few made use of contemporary macro-conflicts as material for their work, but as we moved from venue to venue, the general feeling was that our attention was being drawn to the frictions that exist in everyday life, within the world in which we live today, beyond wars or politicians. Our home, our neighborhood, our intimacy and inner selves, our methods for domestic order and the complex layers of the urban experience: let us talk about ourselves. What was it that shattered us in the beginning? What has caused us to address members of our own species with such violence? Here, we had artists telling us stories of exclusion, overcrowding, abuse or harmony within their own homes and those belonging to others, suggesting that growing up within a certain family or community can also bring along with it the imposition of a culture or identity that may feel foreign to our own souls, which in turn can lead to rebellion and opposition.

“Why these personal anecdotes? Don’t they seem rather insignificant and self-referential in relation to a prominent, international biennial, especially in the face if the grim political reality surrounding biennials right now? Yes, of course. But as individuals, artists or curators, we have little power alone, and would have even less is we did not continue to share our stories.” – Elmgreen & Dragset, 2017

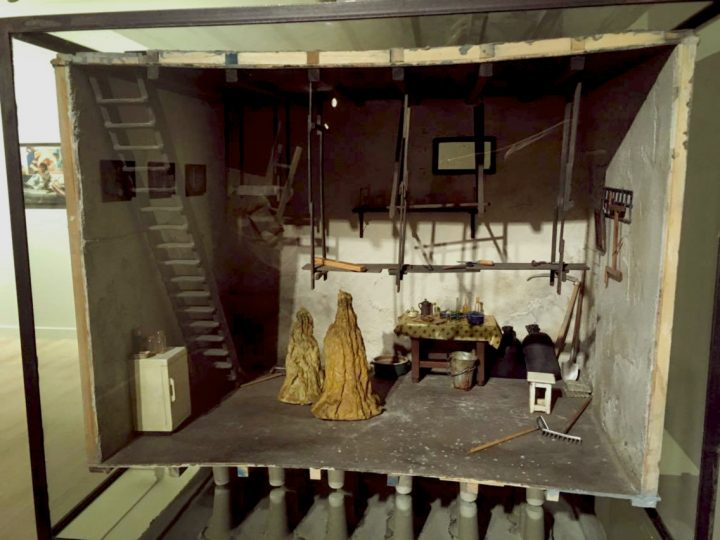

Making use of the platform that was provided by the venues chosen for the Biennial, some of the artists created site-specific installations at each venue that directly questioned the institution’s authority in their role as educators and shapers of identity, since these places (schools, museums, and in the case of Turkey, public baths) are extensions of our own homes.

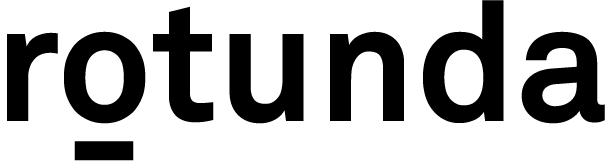

An installation addressing the role of blacks in the Ottoman Empire.

A concrete installation related to classical paintings.

But what were the artists trying to transmit through their exchange of stories? For a moment, let us play with the idea of considering one’s home as a planet. For some, this could be considered as a warzone, where different cultures (personalities) with different interests coexist, delimited in geographical zones (rooms), along with the existence of a hegemonic system, in which the strongest imposes its moral order and economic system. From a young age, we understand that we are invaders inhabiting a foreign territory, and that in order to do so, we must adapt to the imposed rules, right? But as we transition into adolescence, something inside us matures, something that slowly begins to object, to rebel. Not long after, we understand that in order to become the best expression of ourselves, we must leave the nest and create a territory of our own. Nevertheless, there is something about our home that calls to us during moments of crisis: a sacred refuge, which no matter how conflictive, still holds appeal to our inner child, and we continue to return to it. We maintain a relatively open diplomatic relationship that allows us to come and go from it as we please, especially when it offers a stronghold in times of war.

“The more we reflect on the tyranny of the home, the less surprising it is that the young wish to be free of its scrutiny and control. The evident nostalgia in much writing about the idea of home is more surprising. The mixture of nostalgia and resistance explains why the topic is so often treated as humorous.”

– Mary Douglas, ‘The idea of a home: A kind of Space’, in Social Research, Vol. 58, No. 1, Spring 1991, p. 287.

Others may think of one’s home as a sanctuary. A place where everything has always functioned in a harmonious way, an environment that holds no space for crises. By remaining unaware of difficulties and lacking the knowledge of how to deal with them, we attempt to make our lives remain imperturbable, considering the factors that comprise it as immovable in order for this to happen. Religion, morality, and exceedingly traditional social classes often play the role of these pillars, which are tacitly transferred to us through our families and within our communities. Later, the values and customs that give us a sense of harmony shall become threatened by the beliefs of others, by realities built on other pillars. We shall debate their dogmas and destroy their structures, not only in order to protect ourselves, but also after proving that our way of life is a successful alchemy, one which we selflessly wish for our neighbors, assuming that they haven’t been exposed to such a such a harmonious environment.

Now, if we scale these behaviors (or any structure that has been transmitted to us through our homes) to the street, to our work environments, to our politics, cities and countries, we may begin to catch a glimpse of our own conditioning. Do we perhaps seek to impose our own structures, determinedly basing ourselves on our own experiences to say that they are more effective and beneficial for constructing communities because we consider them to be sustainable from our own subjectivity? Or is this in order to defend our own territory, in which we feel threatened?

These are the questions that the Biennial was inviting us to ponder. By exposing their intimacy, the artists gently asked us about our own stories, our own breaking points, our own understanding of the concept of “territory” and our own ethical legacy. Faced with an immensely diverse variety of identities and opinions, and appealing to our sensibility through the use of simple, identifiable materials, as well as with a broad range of techniques and supports, they insist upon respectful co-existence, based on the ignorance of the experience of others. Assuming this is the first step towards expressing deep respect. This wasn’t the place for presenting solutions or alternatives, but rather, it is the place in which to remind us of the common foundations that we as humans all share. To understand each other as migrants from our cribs. Invaded and invaders. Escapists and fanatics. Moralists, rebels. Everyone.

“In times where political problems are looming so large they seem ungraspable, inaccessible and unfathomable to us individuals, we hope to bring politics home – back to its roots. The microcosm reflects the macrocosm and vice versa.” – Elmgreen & Dragset, 2017

Taking place after Venice and Kassel, the 15th Istanbul Biennial brought us back to solid ground, leaving behind worldwide contemporary art tendencies and assuming the role of an indulgent master. Is it possible for us to recover this range of values in a world in which we classify ourselves according to our origin, belonging, and possibilities for permanence? How shall we manage to suppress our rebellion reflex, in order to give space to empathy and dialogue?

Español

Español