An essential line in Miguel Soto’s work is the enlargement of particular objects with fascinating stories, often connected to the author’s own life. A trace of a narrative that eventually forms a portmanteau of collected significant objects.

By Àngels Miralda Tena | Images courtesy the artist | Photography by Matthew Neary

A Sentimental Sculpture: Story of a Young Man

When an object is carried, it gains a weight. A sentimental attachment. An object’s provenance adds to its history, a distinguished, valuable lineage based on human interaction and ownership. But in order to move, the object must contain the property of portability, or “portable property” as described by Mr. Wemmick in Dickens’ Great Expectations.[1] (1861)

During the 17th and 18th centuries upper class European men made the fashion of performing the grand tour. Traveling around the continent for several months to a year, they experienced new cultures, commissioned paintings, and met the continental families of note. This rite of passage established a new literary genre – the sentimental novel: a traveller’s tale, in which quotidian situations are wrought with the passion of sentiment, the banal is dramatized, and emotion takes precedent over the rational function of things. [2]

Paris, Dresden, the Venetian lagoon; it is no wonder that the sentimental novel coincided with the invention of the modern souvenir. By the late 18th century it was common to find china mugs and novelty sewing boxes emblazoned with the name of a place. A keepsake sentimental object to be brought away. These mementos developed from the antecedent of the souvenir, the synecdochic items carried away from sacred sites of pilgrimage. Stones, sand, and twigs were believed to carry the magical properties of the holy sites to the homes of pilgrims as cherished relics (ie. the water of Lourdes).

Souvenirs often take the form of monuments in pocket-size. They might be a keychain, a magnet, or a collectible mug. A kitsch representation of a kitsch form of art. Monuments are kitsch because they are produced to suit popular tastes rather than high art palates. In “The Avant-Garde and Kitsch” (1939) Greenberg considered political kitsch as appealing to the sentimental taste of common people who admired the oversized public monuments glorifying national regimes.[3]

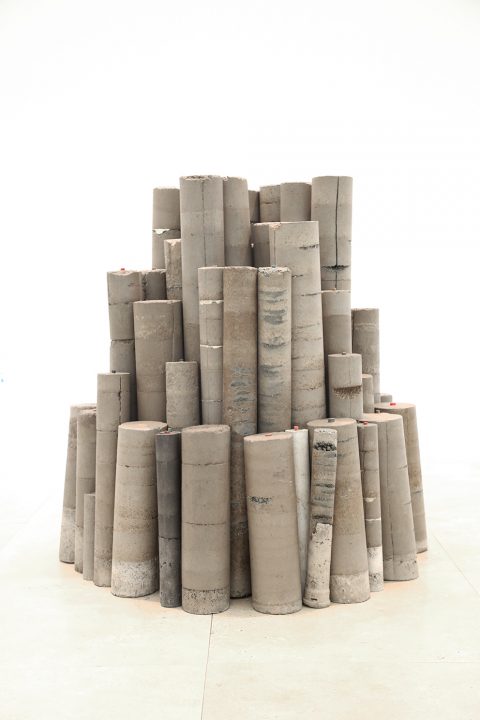

From the above we may extract a set of qualities for the sensibility of sculpture: between material falseness and truth, movability and site, authenticity and replica, concept, or object to behold. A fallen greasy-pole, traditional pastime of common folk, becomes a toy snake of monumental dimensions. A parasol, similarly of an upright function, is aggrandized and lopsided – adding the drama of a limp wrist to the erect structure. Core samples from the Dalmatian coast are stranded in bureaucratic offices whilst being shipped for sentimental purposes – a sly nod to the Brancusi joke about importing A Bird in Space.[4] (1923)

This is an essential line in Miguel Soto’s work. The enlargement of particular objects with fascinating stories, often connected to the author’s own life. A trace of a narrative that eventually forms a portmanteau of collected significant objects. The treatment of things gives them significance of form, selection, and context. Their combination could be likened to Henry Mackenzie’s The Man of Feeling, (1771) organised into vignettes, or chapters, each a short story of its own – the expression of sentimentality which can only be expressed in moments.[5]

A series of fragmentary wholes.

A type of monumental souvenir.

Àngels Miralda

New York, January 2018

[1] Mr. Wemmick makes a habit of visiting inmates on death row. They, no longer in need of their portables hand them over to Wemmick who describes portable property as that which can be carried and easily exchanged for cash. Wemmick’s own non-portable property is modelled on a medieval castle equipped with a moat which puts the two sorts of properties in ideological opposition. The first, a modern possession easy to exchange high in liquidity value, the second of the older type with lineage, heritage, and old-fashioned.

[2] Laurence Sterne’s A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy (1768) was one of the first of its kind. Based on his own journeys, the novel became a model for travel writing of the age.

[3] Clement Greenberg, “The Avant-Garde and Kitsch”, The Partisan Review, 1939.

[4] In Brancusi vs. The United States, the import tax in 1926 of the sculpture was levied as “kitchen and hospital supplies” which were to pay a 40% tax. Artworks could enter the United States free of tax but Brancusi’s sculpture did not fit the description of sculpture: “reproductions by carving or casting, imitations of natural objects, chiefly the human form.”

[5] The Man of Feeling is a fictionally fragmentary novel. Mackenzie organised the book in vignettes with chapters missing. He highlights the missing chapters by organising the page numbering in a certain manner and describing new characters as having been previously mentioned.

Español

Español