Notes of a conversation in Berlin

By Ana Rosa Ibañez | Color Images: Carolina Martínez Sánchez | Black & White Images: Ana Rosa Ibañez Translation: Manuela Baldovino

The first image of Amalia Valdés I am able to summon from my memory is from Taller Bloc (Santiago, Chile), during her residence there in the year 2014. I remember her bent over her work table, producing what I believe were her first pieces that manipulated aluminum. At that moment, I didn’t know I wanted to write, and I wouldn’t have known what to write about her work, either. But life takes its course and people change, they meet in other places, in other realities. In December, we had the opportunity of traveling together to the Atacama desert, a place that invites you to reconsider, to mutate, and in this process, we found each other. Today, with both of us living in Berlin, and both of us at a different stage in our professional lives, we have had several opportunities to talk and exchange ideas about our opinions and experiences regarding art, migration, and local Chilean identity in opposition to one inserted into a global context. Writing about Amalia has now taken on a deeper, more special meaning; I confess that I’ve even used this piece of writing to reflect on my personal process of living outside of Chile, or perhaps on that of many people who, like me, are ruminating on these concepts. Amalia’s piece “Made in Germany” comes to illustrate the process of opposition and identity crisis that the artist experimented during the months of at Für Alles Mögliche, the residency program she was invited to participate in. Presented at the Raue Strömung exhibition in Berlin this past July (as part of a collective exhibition of Latin American artists at the Eigenheim Gallery, located in Berlin’s Mitte district) was a Chakana cross (which she has been developing for a few years now), a millenary symbol belonging to the indigenous people of the Andes Mountains.

This article’s contents come from a conversation that took place between us a few months ago, in which we talked about Amalia’s work and her transformation over the last few years. We looked back on Taller Bloc, on her attending Eugenio Dittborn’s workshop, and we put into perspective the evolution from her first pieces to her latest production with sacred geometries and her carefully studied color palettes. Since then, several other moments that have allowed us to develop our ideas together have come along, which I shall incorporate as well, without differentiating which one was when. A long interview that carries on and on, or perhaps by this point, a fictitious narration.

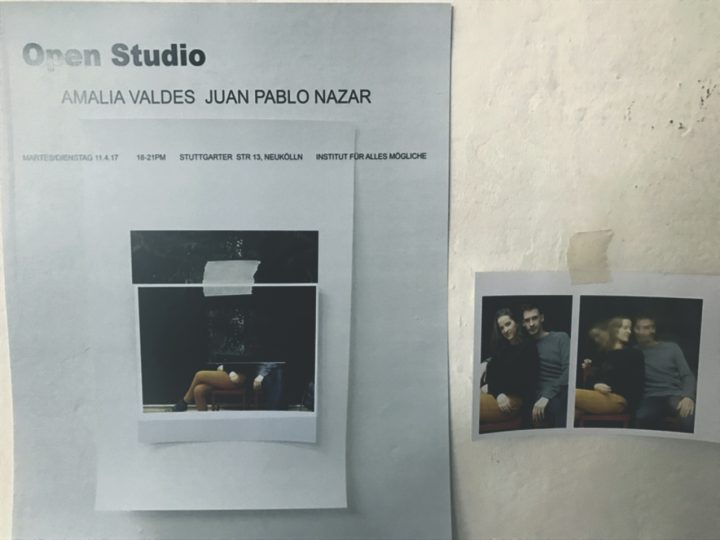

It’s a Thursday during summertime in Berlin, and the sky is pouring with rain. On my way to Amalia’s studio, I decide to stop at a café and wait for the rain to pass, but as the time we had previously agreed upon draws closer, I am forced to face the fact that it’s not going to die down, and mount my bicycle once more. When I arrive at 13 Stuttgarter Strasse, I find Amalia at work with her door wide open. This is probably to make up for the slight closed-in sensation that comes from sharing the 50 square meter living and working residency space with her husband Juan Pablo, an artist and architect, for the past six months. A drastic change from their apartment in Santiago, but one that that suited them nicely, especially in terms of creativity. The couple has managed to transform space, focusing their activities on their studio and on the discussion and production of their pieces. The residency’s name, Für Alles Mögliche (For All Kinds of Things), is an accurate description of what it entails: an invitation to develop whichever potential lies within the residents. Upon entering, I literally undress myself, as I’m soaked. Amalia, in spite of being considerably smaller than me, lends me a sweatsuit and offers me a cup of tea. Amalia has just arrived from the “2017 European contemporary art tour”, consisting of Documenta 14 Kassel and Münster, and she had already assisted the first days of the Venice Biennale, a combo that occurs only once every ten years. I imagine that her head must be filled with information, but she seems calm in her Chilote yarn slippers, listening to Bach’s flute sonatas.

I want to start off by talking about a Chakana made in Germany. But in order to understand it, first one must comprehend the emotional process implied by the migration she has undertaken. To take some distance from a Latin American identity, and what has led her to return to herself, questioning her identity in a global context, always iterating a symbol that holds her captive, that looks after her like a shelter in this ocean of information that is the old European continent.

This is how we began to talk about the art events that she had just visited, from her perspective as a Latin American artist with tremendous expectations after having heard all the stories and myths throughout her entire career:

Amalia Valdés: I think that the best event I was able to attend this year was the Venice Biennale. Nevertheless, there is a double-edged sword with regards to the budgets that have been amassed for these events and what this means for the artists who participate in them. Let’s take Damien Hirst, for example: someone who’s not participating in the Biennale, but who decides to inaugurate his latest show around a month before the Biennale opens. He uses the opportunity to put a spotlight on his work at a moment that doesn’t belong to him, overshadowing the Biennale’s curatorship. So much gold, such a large budget, but evidently revealing that there was no reflection behind this, no consideration for places: it was a display of power, a show. And this deforms the Biennale, it transforms it into a different sort of event, something more commercial, the sensation of being for sale.

Ana Rosa Ibañez: Yes, I think that it’s good for someone like Damien Hirst to exist, someone who holds shows at galleries and has his audience. I think it’s fair and entertaining, but the way in which he imposed himself at the Venice Biennale is disquieting to me; it makes me profoundly suspicious of the organizers and the people involved.

AV: Sure, well, then I realized that he has close ties with the owners of the Punta della Dogana and the Palazzo Grassi, who belong to one of the richest families in Italy. I find this very strange. On one side, the “discourse” behind Documenta 14 and Adam Szymczyk is centered on looking outside of powerful countries, trying seriously to incorporate Asian, Latin American, or African perspectives. For this same reason, they’ve incorporated Athens as a new exhibition hub. But this isn’t perceived through the exhibition’s contents, it’s not evident, it’s not true. You see a lot of German artists talking about the World Wars, etc., very focused on their own themes and history, which —in spite of being very important and interesting— have already been reviewed at length. In spite of this, I thought that the piece by Marta Minujín (Argentina) was extremely appropriate. This was a re-installation of a piece from 1983, in which she presented a Parthenon of books that were prohibited by the Nazi state, something completely ad-hoc with the curatorial line, with the economy of materials and totally at the level of a biennial, but coming from a South American artist. A reflection that was a lot more powerful than the approach the Europeans themselves took towards their history. At Documenta, I ended up feeling that, true to its name, there were too many documents: you had to read a lot to understand each piece, and this was very tiring. It was like there was an attempt to justify each piece before even being able to appreciate them.

ARI: In Europe, I’ve noticed a constant quest to attain orgasms through archives. From my experience in England, I realized that the art scene had been turned into a cycle that surges from some hole or detail in some archive of some historical city, and the from there comes the production of a piece of art, which must be registered in some way so that upon being archived, it allows for an ongoing dialogue with some other archive addict so that another piece can come from that. It’s a cause-and-effect sequence that, in my opinion, tends to overshadow the piece itself; it makes me question the concept of the piece as such. What are the limits and requirements needed in order to define it? I don’t criticize this method when it’s justified, but it seems like a fad, and it makes me think about the loss of meaning and about being drowned in information. Instinctively, this drowning feeling has led me to seek out a breath of air in more ephemeral pieces, in works of art that leave no traces, in pieces that happen and come to an end; I appreciate the fact of not registering. A piece that channels an invisible energy, and that vanishes in its honor. But I know that this is a utopia. I also understand that it is also beautiful and necessary to register a work of art, but I would like to dream about this not being a fundamental part of the piece, as it is today. To me, it seems that some art intellectuals get off by archiving anything that moves inside an exhibition space.

AV: Yes. I think that that’s what libraries are for. I respect people who make these kinds of pieces, but to me, it has to do with their initial impact, with surprise. With their immediate conquest, with magic and alchemy. After that, if I connect, I’ll probably be interested in getting to know the process. But I like this mystery.

ARI: To let the piece itself work as a synthesis of its contents, context, and influences, but communicating itself in a sensitive rather than literal way…

AV: Everything is reflected through your piece, including the different periods that one goes through as an artist. I’ve always painted, and during this period in Berlin, I haven’t painted a thing. I’m in a different process, a different investigation. From my same center, but I’m not immersed in that meditation that comes from painting, I haven’t had the time to sit down in front of a canvas. I’m experimenting with different work processes, exhibiting, getting to know people, and looking around a lot. I’m benefiting from this special year in Europe, in which Münster, Documenta and the Biennale all coincided. It would be irresponsible not to nurture myself from that. In Chile, unfortunately, people are a lacking this a little: being able to see a good contemporary art exhibition. Of course, there are some, but it only happens on occasion. Only since recently, through Corpartes (a private institution), we are having access to more important exhibitions on an ongoing basis. Being here has implicated absorbing as much as possible, it’s the Mecca.

ARI: Do you feel like you’ve been able to digest anything of what you’ve seen?

AV: Nothing. My initial plan for the residency was to stop for a little while. Over the past few years, I’ve been producing one exhibition a year, which is a lot for me. I wanted to absorb, to read, to work through all the pending matters I’ve accumulated, but I’m here and I haven’t stopped. Opportunities have come my way, and it’s been impossible to say no to them. It’s beautiful, the world has really opened itself up to me in order to meet people and do things.

Amalia’s stay at the residence has been far from quiet. Just one month after arriving, she and Juan Pablo held an Open Studio, in which they showed their work for the first time. Immediately after that, during the month of April, she inaugurated her first individual exhibition in Cologne —“Estrella Sur/Südstern”— at the Seippel Gallery, founded by Ralf Seippel. The gallery owner got to know Amalia’s work at an art fair in Canada, where the artist was being represented by Yael Rossenblut. He fell for Amalia’s work, and today, he is her main agent in Europe. The exhibition was solely dedicated to showing her stainless steel pieces (http://galerie-seippel.de/amalia-valdes).

Following this exhibition, at the beginning of May, the couple was invited to participate in the One on One project, where they worked on a piece together for the first time, in a dialogue with Korean artist Ae Hee Lee, as part of an exhibition that took place for a single day. In June, she inaugurated the exhibition that we discussed at the beginning of this article, and the week after that, her work was exhibited once more at Cologne’s Gallery Night as part of the gallery’s solo project. Sieppel is also showing Amalia’s work at Art Pampelonne in Saint Tropez. In addition to this, she has just exhibited her work once again at the Korean space Dam Dam Gallery along with her husband Juan Pablo, and they shall follow this up with their final Open Studio at their residency in Neukölln.

ARI: I can imagine that in this whirlwind of productivity, you’ve also seen new ideas appear through doing, in spite of not having time to sit down and think about the direction you want to take.

AV: Of course, new ideas come up. I feel more creative than ever. Each piece leads me to the next idea, the next possibility, to other objects. Geometry has infinite possibilities. You define a space, and that space can be modified an infinite number of times; you can combine, create, and diversify. And now that I’ve been intervening spaces —doing more site-specific work, in this case, working with the ground— I’ve truly realized that I can do whatever I want, I can make anything my own. I can come up with a great number of possible projects that go can into my archives, and may perhaps never be carried out.

ARI: Both you and your work have gradually expanded and adapted to the space that surrounds you.

AV: Of course, as well as to new media. Here, I can’t paint due to lack of space and time; I don’t have my studio. This is the moment to experiment, to do other things, to pick up new tools and new ways of communicating. Another important lesson that I’ve picked up here is to be more confident in my discourse. I feel that in our country, we often deprecate ourselves when referring to our own work. Here, your discourse can be whatever you want it to be, and everyone will respect it. Whoever is interested, good for them, and whoever isn’t, good for them, too.

ARI: I remember having a few embarrassing experiences in the beginning, when upon being asked for my opinion, I naturally tended towards giving negative critiques. Today, I realize that it wasn’t what I felt or what I thought, nor did it offer much of a contribution to the conversation, but rather, that it was due to that competitive instinct of placing oneself above the situation. Of having a powerful opinion instead of truly being interested in the artist’s opinion. My mistake.

AV: I feel that the atmosphere in Chile tends to be rather critical. It’s very easy to fall into that. I try to focus more on what’s positive, because constant critiquing can shut off your own fluidity.

ARI: Going through all these processes focused on Europe, you decided to work on a piece that remounts to your past, to a symbol that seeks to reconnect with an Andean identity, instead of reflecting your distancing from our continent. Talk to me about the Chakana.

AV: The first time I used this symbol was for a fair in Puerto Varas in 2014. I had several pieces from the show at Artespacio that were modules. My initial idea was to achieve all the combinations that were possible with these 60 modules and to generate a larger symbol, and this led me to reproducing a Chakana with an invisible background generated by these geometric modules. I investigated some more and liked the correspondence between this symbol and the indigenous people from the Andes, and the theme began to expand. It’s a very powerful and archaic image that has been present for about 4000 years, within several cultures, and in all of them, its primary meaning is the connection between the sky and the earth. The superimposed platforms formed by the circular staircase that unite the two worlds also refer to the infinite, connecting to astrology through sacred geometry; this really moved me.

ARI: Do you feel that the Chakana brings you closer to these notions when you work with it?

AV: I consider myself to be quite connected to these notions from before this. I like to listen to myself and connect with my ancestors, with my masters who have somehow set out guides for me. I feel that the Chakana arrived to me because it’s the way it had to be. To sit down and bend, manipulate, select and classify brings me to a reflexive mantra state through my body. I feel connected to it from remote times. This is where we go into more profound or mystical issues (laughs).

ARI: Let’s go, let’s go!

AV: I feel that I’ve lived in other places and in other lives through art, communicating with people through doing, producing, and creating. To me, the Chakana has a lot to do with that, with creation, with a deep connection with the earth as well, which is where I’ve always found my refuge. The Chakana is very present in that; it’s an image filled with natural and mystical symbols that can gradually connect channels.

ARI: Sacred geometries such at the Chakana are considered to be products of both cerebral hemispheres at the same time: the right one for being related to artistic and spatial skills, and the left for being related to math and logic, acting as a conduit for both energies, achieving a more holistic connection with spaces and nature. At the Raüe Stromung show, your piece hung on the wall, shining like a talisman. An Andean cross made in Germany, but built out of metals from the Andes Mountains, without renouncing its true identity. It made me think about the concept of “otherness”. Here, we find ourselves swimming in information, amongst enormous amounts of archives, museums, and galleries. I must confess that I went (and am still going) through a considerably deep identity crisis, and strangely, my lifesaver was writing my curatorial thesis on Latin American cultures. It’s strange to think that for some people, when they’re in their own country, surrounded by people that come from more or less the same cultural context, it’s uncommon to walk down the street questioning what defines them culturally, or what the pillars of their identities are. But when you’re facing a culture that not only opposes, but also imposes itself, one’s first instinct is to learn it, imitate it, absorb it; however, what comes immediately after that is to find oneself inside of it, to appreciate oneself, and to find the inner strength to disregard it. It’s a concept that has been developed at length by philosophy, and one that I still find entertaining to think about.The survival instinct, a vital impulse that keeps us from falling into a cultural abyss, has led us to the search for symbols, sounds, or forms that connect us to our roots or to the concepts that define us, and we cling to them. Deleuze and Guattari, in their work Capitalism and Schizophrenia, suggest a complete detachment from all notions of identity: a body without any organs. I don’t know whether I’ve gone this far. The Latin American identity is a strong thing. In any case, I found it beautiful to hear that you’ve been experimenting intensely with your artistic capacities for the entire year and that in spite of this, almost at the end of your residency, you show this symbol, literally lifting it from beneath the ground like a talisman that says, “Yes, Europe walked over me, but here I am, shining like the Chakana.”

AV: That’s a nice interpretation. I’d love to use it again; I feel that at some point, I’ll be able to understand it in more depth… or perhaps not. In 2014, I used this image for no real reason, but now that I’ve studied the image, it makes increasingly more sense to me. Over here, I’ve learned several things that are very important to my work, but the strength I’ve been able to gather comes from being here and feeling foreign. From asking myself at Documenta, where is Latin America in all of this? We’re so powerful, and yet we have no presence at these kinds of events. They feel that they’re opening up to unknown artists, and the truth is, they’re still missing the big picture.

ARI: And further up ahead? Do you know what’s in store for you?

AV: Good things, I hope (laughs). I’ve been invited to show my work at the Korean embassy. We met the curator through the institute. A one-day event in which an artist from the Institute speaks (through the piece) to a Korean artist selected by her. She was very interested in sacred geometry, and wanted to continue to the exhibition and present it at the embassy. We’re also holding another Open Studio at the residence. We have to decide when and how to do it. And after that, well… to rest and make the best of what the city has to offer, summer in Berlin with the freedom to do whatever I want!

Español

Español