“Why would the work of a Latin American artist be of such interest here? In fact, the guides at Bildmuseet have been explicitly instructed not to mention, or comment on the circumstances of Ana Mendieta’s death.”

The visual artist and performer Carla Garlaschi give us her particular and exquisite review of the latest exhibition of the artwork of the Cuban artist and performer Ana Mendieta at Bildmuseet, Sweden.

By Carla Garlaschi | Images courtesy of Bildmuseet and Galerie Lelong, NY

We were going to spend a weekend taking mushrooms. Someone said it would be a decision-making experience. The mushrooms came in transparent bags and they were dry. I chewed a few of them, mixed them with squares of chocolate and swallowed. We were several friends who had met at art openings staying in a house in Cajon del Maipo. We had brought all kinds of fruits, seasonable vegetables, meat, cheese and alcohol. Some of us went to the banks of the Maipo River, took off our clothes, smeared our bodies in mud and waited for it to dry. Suddenly, I saw the hills as wallpaper, as great, theatrical curtains, with patterns of greenish serpentine figures.

But that was a long time ago. Now, I am in Sweden. I am visiting the exhibition Ana Mendieta: Covered in Time and History at the Bildmuseet in Umeå, a city in the far North, destroyed and re-founded several times, burnt down tirelessly by the Russians, populated, abandoned and repopulated. Today, Umeå is home to metal bands, punks, the traditional left and thousands of university students. It’s a far cry from the cover-looks of Stockholm. It took Bildmuseet eight years of negotiations to secure the exhibition. Why would the work of a Latin American artist from the 1970s be of such interest here? Does Ana Mendieta’s tragic and still mysterious death appeal to the Swedes’ love for thriller’s and crime novels? That sounds too fanciful, like a bar tender’s conspiracy theories. In fact, the guides at Bildmuseet have been explicitly instructed not to mention, or comment on the circumstances of Ana Mendieta’s death.

Before entering the museum, I chat with a glocal, a male European artist, who tells me how annoying he finds it that they show Mendieta, because she fullfils all the necessary requirements for a politically correct exhibition. Anyhow, I go in. The black walls make for a solemn reception. In Sweating Blood (1973) drops of blood fall on the artist’s beautiful head. In Burial Pyramid (1974) her petite body is covered in mud and rocks or, in Creek (1974), immersed in the waters of Mexico showing her back to the viewer. She floats almost motionlessly as if preserved in some resin of grainy, visual memory; a wispy Ophelia or – somebody else might think – just another American Apparel model. If the latter sounds impertinent, it is probably because speaking of Mendieta’s work, one seems to have to walk on egg shells to avoid saying the wrong thing.

I think about Lucy Lippard writing: “When women use their own faces and bodies they are immediately accused of narcissism (…) Because women are considered sex objects, it is taken for granted that any woman who presents her nude body in public is doing so because she thinks she is beautiful.” [1] And Simone de Beauvoir when she describes the aversion of children to recognize in their own parents the origin, especially in the mother, who reminds us of our own animalism, our carnal origin. [2] But then, Mendieta didn’t get along that well with white feminists.

Ana Mendieta went from being the child of a highly respectable Cuban family to being an unaccompanied, exiled pre-teen in the U.S. under the tutelage of “Operation Peter Pan.” [3] The considerable prestige and social status of the Mendieta family – there has been a Mendieta who was revered as a hero of the Cuban independence as well as a president Mendieta – were lost when Castro came to power. In the U.S., ethnic difference turned her into the ‘other.’ And in the reception of her work, the prevalent ethnocentrism of her time (which still exists) hardly distinguished anything beyond the figure of the exotic. Her work has been seen through that patina, through the West’s nostalgia for ‘the savage,’ ‘the authentic,’ ‘the primitive’ which the Third World exudes in the eyes of the first. [4]

I am probably as disturbed by this exhibition as the European glocal claims to be, but for entirely different reasons. Today, I watch her videos, as if visiting the media archive of the origins of the stereotypical work expected from a Latin American artist. But what is now a format of easy commodification, was at the time an unintelligible scream. If the artist personifies exile, she also exiles herself from being a woman in the way white feminists would have her be a woman. In response, exaggeration becomes her survival strategy. “Not of purity, not of saying less, but rather saying more, of saying too much, with accent and intonation, of mixing the metaphors, making illegal crossings, and continually transforming language so that its effects might never be wholly assimilable to an essential ethnicity.” [5]

But now, in 2017, with the continuing growth of the Fourth World, made up of non-assimilated immigrants, more tightly connected to their home countries through internet and social media than to their places of migration, now that the possible suspension of DACA by the Trump government could lead to the deportation of Latino Dreamers from the U.S., what could be the strategies of the Latina artist today?

Socrates died, sentenced to drink poison hemlock, Marat was stabbed in his bathtub, Virginia Wolf committed suicide, Rimbaud died in a hospital, both legs amputated, Victor Jara, tortured to death, Bas Jan Ader disappeared into the Atlantic Ocean, Simone de Beauvoir died of pneumonia. In the late 1990s, the artist Coco Fusco performed Better Yet When Dead, a series of wakes for Latina women who became famous for their dramatic, untimely deaths – Frida Kahlo, Evita Peron, Selena, and Ana Mendieta. Fusco explains that “at that time it seemed that the only way a Latina could gain attention was to die dramatically.” [6] Death says something about those who lead the lives that lead to it, and about their social context. I see no reason to ignore that. Maybe we’ll never know if Ana Mendieta was murdered by Carl André, but the question, still asked activists around the world, is still valid: Where is Ana Mendieta?

And by extension, what does the show of Ana Mendieta’s work in the Bildmuseet really signify to me? Looking at the museum’s past agenda, it strikes me that the few non-Western artists exhibited there, have either been based in their countries of origin, such as Brazil or China, or in an international art centre, like NY, but never in Sweden. It seems safer to deal with a faraway, foreign imports than doing the risky labour of digging into the rich, local scene of non-European artists. Or let me phrase it simpler, if Ana Mendieta uttered an unintelligible scream forty years ago, who has the courage to look for the unintelligible now and here?

[1] The Pains and Pleasures of Rebirth: Women’s Body Art, Lucy Lippard, 1976.

[2] Paraphrased after Le Deuxième Sexe, Simone de Beauvoir, 1949.

[3] Operation Peter Pan (Operation Pedro Pan or Operación Pedro Pan) was a mass exodus of over 14,000 unaccompanied Cuban minors to the United States between 1960 and 1962. Father Bryan O. Walsh of the Catholic Welfare Bureau created the program to provide air transportation to the United States for Cuban children. It operated without publicity out of fear that it would be viewed as an anti-Castro political enterprise.

[4] Paraphrased after Where is Ana Mendieta?, Jane Blocker, 1999.

[5] Where is Ana Mendieta?, Jane Blocker, 1999, quotes The Pachuco’s Flayed Hide: The Museum, Identity, and Buenas Garras, Marcos Sanchez-Tranquilino and John Tagg, 1991.

[6] Coco Fusco on the Enduring Legacy of Groundbreaking Cuban Artist Ana Mendieta, Jared Quinton, 3rd February 2016. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-ana-mendieta-s-enduring-legacy-in-the-words-of-coco-fusco

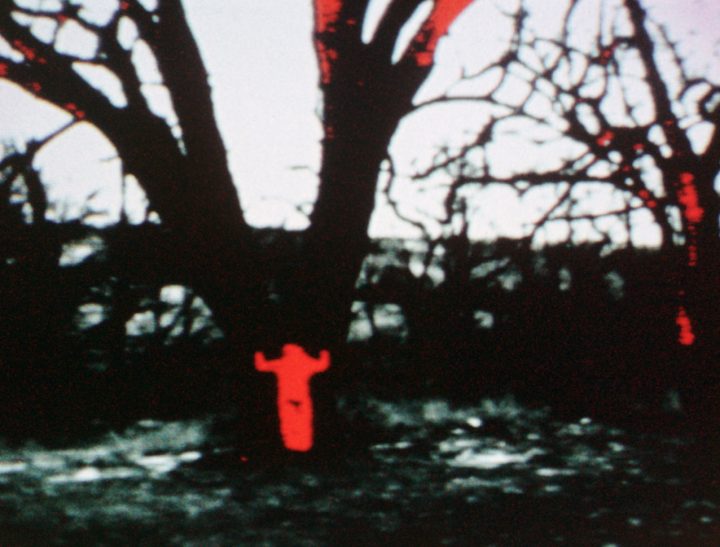

Image 01: Anima, Silueta de Cohetes (Firework Piece) (film still), 1976. Super 8 film, color, silent. The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 02: Sweating Blood (film still), 1973, Super 8 film, color, silent. The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 03: Energy Charge (film still), 1975, 16mm film. colour, silent.The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 04: Blood Writing, 1974 , Super-8 color, silent film. The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 05: Blood Sign, 1974, Super-8 color film (silent). The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 06: Creek (film still), 1974, Super 8 film, color, silentThe Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 07: Volcán (film still), 1979, Super 8 film, color, silent. The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 08: Untitled: Silueta Series (film still), 1978, Super 8 film, color, silent. The Estate of Ana Mendieta Collection, LLC. Courtesy Galerie Lelong, New York.

Image 09: Ana Mendieta, Omsluten av tid och historia (utställningsvy), Bildmuseet, 2017.

Image 10: Ana Mendieta, Omsluten av tid och historia (utställningsvy), Bildmuseet, 2017.

Español

Español