By Christian Viveros-Fauné | Images: Courtesy of the artist | Installation images: Jorge Brantmayer

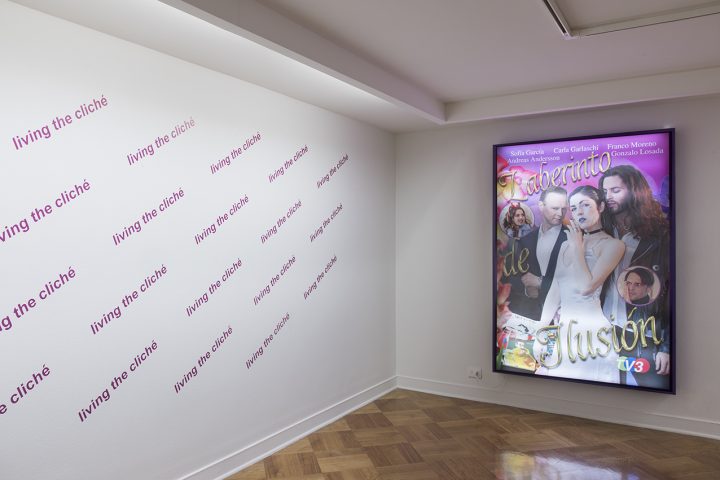

The fact that the phrase “living the cliché” covers the entire wall of the gallery D21 Proyectos de Arte in Santiago, Chile, tells us a great deal about Carla Garlaschi’s newest attempt to satirize the art world. The words refer to, among other demoralizing possibilities, the ubiquitously contemporary experience of doing something only to realize that you have already seen this film, TV show or Youtube video before. The horror!

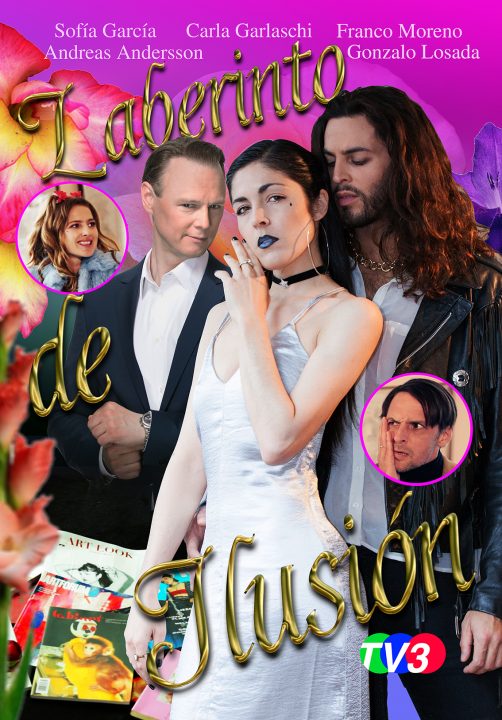

Titled after a video by the same name Garlaschi shot as the centerpiece of her recent exhibition, Laberinto de Ilusión (Labyrinth of Illusion) unfolds across one of Chile’s better-known galleries like a perverse joke. Instead of displaying straightforward paintings and sculptures inside the art space, the Chilean artist has chosen to exhibit several lightboxes sporting her own face, a wall of printouts taken from her Instagram account, and a large illustration that details, via fourteen photos and text descriptions, the stock characters that populate her hackneyed histoire d’artiste. Crucially, the narrative is relayed through the use of what has long been one of Latin America’s greatest and most impoverished cultural exports—the telenovela— or as she puts it ‘banality as camouflage’.

Garlaschi’s videotaped tale—which tells the story of “La Niña,” her artistic alter ego—embraces every cheap showbiz cliché in the book. Her characters include villains and heroes, stooges and straw men. One of them, “The Art Critic,” is told that “his concepts are nothing more than a postcard in an ethnographic museum” before having a wine glass smashed in his face. Others include “The Argentine Theorist,” “The European Curator,” “The Swedish Princess” and “The Artist-Drug Dealer.”

Laberinto de Ilusión resembles the typical Latin American telenovela in other spectacularly clichéd ways, too. Rather than advance through proper plot and character development, Garlaschi’s narrative unfolds, as its common on this genre, almost exclusively via the use of stereotypes and binary oppositions—i.e., love and hate, work and family, art and life, and a great deal of flaming camp.

Modeled after a format that is the entertainment equivalent of fast food, Laberinto de Ilusión employs the archest kind of irony to lampoon the expectations of artists in Santiago, Chile—and other points on the map where artistic excellence is falsely conflated with celebrity and financial success. The American painter John Currin once said that he owed his career to having found a cliché that he could believe in. Garlaschi makes fun of that, too, along with globalism’s obsession with fame, fortune, ambition and romance.

Today, art’s increasingly neoliberal worldview simulates a lot of dumb popular fiction. In Garlaschi’s terms, it resembles the worst possible kind of telenovela. Let’s plainly call it what it is, she suggests: a Laberinto de Ilusión.

Español

Español