“Continuum” at Ala Scaligera in Milan, curated by Antonio Grulli, refers to this initial group of selected artists. Giovanni Anselmo, Vanessa Beecroft, Daniel Buren, Sheila Hicks, Anish Kapoor, Giulio Paolini, Ettore Spalletti: all great masters, of various generations, who work with a wide range of languages, innovating the way in which we look at art and challenging the very concept of what art is today.

By Antonio Grulli | Images courtesy Ala Scaligera

With this project, the Borromeo family renews its historical support for the arts, one which has been ongoing for centuries, doing so this time through a new location. The Ala Scaligera (‘Scala Wings’) within the Rocca di Angera (‘Angera Fortress’) will in fact be a space dedicated exclusively to contemporary arts and creativity, an evocative exhibition venue which will host a series of specially formulated events. Its rooms, visible for the first time following the restoration, have been renovated in keeping with the most modern canons for contemporary art display, while maintaining the historical traces still to be found within them.

The title, Continuum, intends to underline how for many centuries the Borromeo family has maintained the passion for beauty and cultural innovation: a passion which has granted us places today such as the Isola Bella and the Isola Madre, right here in Lake Maggiore, which the Rocca di Angera looks onto. The new structure will make it possible to operate more effectively in the contemporary arena, placing it side by side with the conservation of ancient heritage. The inauguration of the Ala Scaligera represents a moment of great importance, insofar as it is a key part of a setting which in landscape and monumental terms has few equals in the world, and which attracts hordes of visitors every year: a new audience of contemporary art fans may thus acquire the habit of frequenting these places, just as those visitors who love landscapes or art from the previous centuries may come into contact (in some cases for the first time) with the most advanced research of contemporary artists, creating a single research hub that brings together landscape, architecture and art.

But Continuum also refers to this initial group of selected artists. Giovanni Anselmo, Vanessa Beecroft, Daniel Buren, Sheila Hicks, Anish Kapoor, Giulio Paolini, Ettore Spalletti: all great masters, of various generations, who work with a wide range of languages, innovating the way in which we look at art and challenging the very concept of what art is today.

I have always believed that in every exhibition, from the most simple to the most complex, one needs to feature a destabilizing element: something that does not readily fit into the dominating opinion of a given period, something that may unhinge and bring alive even an exhibition hosted inside an exhibitive institution aimed at the general public (and not just those who are already accustomed to contemporary art). It may seem strange, but in this case it is the very link with a non-temporal idea of art that emerges as the most destabilizing feature. Indeed, over recent years, the notion has been impressed upon us that art is closely bound up in its own historical and physical context, and that the concept of universality and capacity to overcome one’s material and temporal limits is the legacy of a now distant past rooted in nothing but romantic fancies. This change set out to rid the sphere of art even of concepts such as the ‘masterpiece’ or the maestro. I, on the other hand, fortunately or not as it may be, continue to believe romantically not only that masterpieces exist, but that art, in its very highest forms of expression, despite being the result of a given historical and sometimes geographical context, is capable of evoking if nothing else the presence of a universal idea, one capable of overcoming our time and presenting itself like a truth clear to the eyes of those who have the sensitivity to grasp it and a receptive enough soul to resonate before it.

This exhibition could be a manifesto for what I have just outlined. In an age in which the trend seems to have become that of the presentation particularly of the most mundane, momentary, transitory and sometimes even deliberately “ugly” aspects—if not indeed focusing obsessively on the most problematic or dramatic elements—of our existence, an exhibition of this kind stands out like an anomaly, the interruption of a flow which otherwise seems unmodifiable.

Few artists on an international level have been able to maintain such a strong bond with the notion of the “classical” and the suspension of time. In all of them there is a surpassing of the strict historical context which in certain cases is accompanied by the quotation from and dialog with the ancient forms of the art of yesteryear. And inevitably this dialog could not but relate also to the setting of the exhibition. Indeed, right from the start, the Rocca and its surrounding territory dictated the choice of artists and works. In particular, three elements of this place emerged as decisive factors in the construction of the Continuum project.

The first element is that of light, peculiar as it is on Lake Maggiore, with its endless alterations over the course of the day and the passing of the seasons: sometimes crystal clear, other times blurred by fog and mist. The Ala Scaligera itself is an extraordinary atmospheric mechanism by virtue of its own structural characteristics. On the first and second floors, the display rooms are in fact characterized by large south and north-facing windows. The light therefore changes tangibly: forceful in certain moments, softer and hazier in others. And the water of the lake amplifies and complicates the presence of light. I am certain that this aspect will always strongly characterize the space, being a factor that one cannot but bear in mind, whether it is to be cherished as a display element (like in the case of this exhibition), or whether it needs to be ignored. The works by Anish Kapoor and Ettore Spalletti are enhanced by their dialog with this poetic dimension, with an ephemeral and unstable atmosphere, for one of the elements of which they are both made up is in fact light itself.

In front of a window on the north face of the building stands a sculpture in alabaster by Kapoor, made up of two elements almost in a sort of intimate dialog which—even in its heaviness and material solidity—is pierced by the light, changing constantly as we observe it from different positions. Two other works of his, reflective dish shapes, are instead positioned on the two walls one in front of the other, and thus alter our perception both of the space around us and of ourselves. The alabaster sculpture and the works on the walls, in their colors suspended between magenta and cherry red, invoke a number of the medieval decorations to be found on the adjacent walls.

In the next room, four works by Spalletti are presented: a wall-mounted piece and a number of stone sculptures. Also in this case, the material used is alabaster, cut into geometric shapes in the classic style of the artist from Abruzzo, with some of the facets covered in light-blue pigments of various shades, while in the wall-mounted work, the blue is enhanced by the presence of thin gold-leaf edging. These are the colors of the light of the lake and the surrounding landscape, and seem to be made of the same material as the mist that often surrounds it.

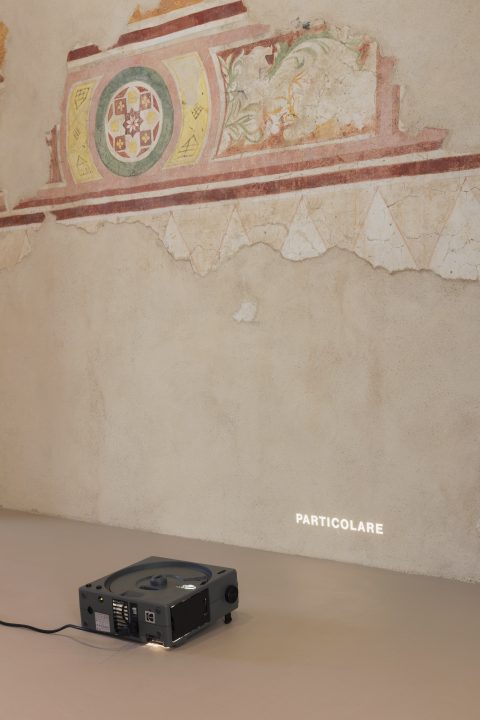

Also the exceptional work in optic fiber by Daniel Buren, inside the multimedia room, is made of light (albeit electric), along with the famous work by Giovanni Anselmo in which the word ‘PARTICOLARE’ is projected by two slide carousels, one of which points towards a wall in the space, while the other is cast onto the bodies to be found moving around the room, intercepting and limiting the beam of light otherwise aimed into the void and infinity.

The second guiding element in the show is diametrically opposed to the first: stone. The geological conformation of the area is visibly perceptible throughout the spaces of the Ala Scaligera. Right from the town, the hefty blocks of stone that the Rocca is made of may be seen. One is surrounded by it in the entrance courtyard, and it may be seen from all of the rooms in the display space. They are mainly light gray rock, at times tending towards the pinkish, squared but obviously fairly coarse. A few steps from the Rocca we can also find a quarry, the stone material of which used to be transported from the Lake to Milan by boat.

Anselmo’s major installation seems to be made of the same blocks that make up the walls of the Rocca, as if they had made their way in from the outside space, just to allow us to climb on top of them and get that tiny bit closer to the stars, to make us aware of the solidity of the force of gravity, and of how we are clinging to a planet hurtling through space, the dynamics of which are endowed with an unchanging truth.

And so like in the alabasters by Kapoor and Spalletti described above, the glow of these local stones also emerges. The architectural composition of stone used instead as an element of construction returns in the photographs of a Palermo performance by Vanessa Beecroft, staged in 2008 inside the Chiesa dello Spasimo church. These are photos inhabited by women’s bodies, mixed with artificial elements reminiscent of classical statuary, such as the three ceramic heads in which the female face disappears to the point of becoming an informal volume that maintains nothing but a vague likeness to the features of a head.

The third and final element is that of time (from which the title arises), which I mentioned at the beginning with regard to the non-temporal dimension that moves through the works. This is probably best summed up in the works of Giulio Paolini, which open the show in the first room, as the ideal introductory chapter. These are works that perfectly exemplify the artist’s modus operandi, often capable of commenting on the statute of art in its most metaphysical and rarified acceptation, one which is then to be found throughout the rest of the exhibition. The first work we encounter is Circo Massimo, a tribute to the gallerist Massimo Minini in collaboration with whom this exhibition was organized; we see a figure, simply outlined in pencil on the wall (it might be a ringmaster or a conjurer) holding an image from which the photos of works by artists who have written the history of the gallery seem to come out, some of whom, like Daniel Buren, are also featured in this exhibition.

The last flight of the stairway that joins the three levels—and which has become one of the characterizing features of the new spaces of the Ala Scaligera and which serves as both a physical and ideal connection with the rest of the Rocca—is dominated by Sheila Hicks’s major installation, redesigned especially by the artist for Angera. It comes down from the ceiling only to rest on the landing at the top of the steps. We start to see it in all its length while still climbing the stairs. Once before it, we may sense its material quality, the peculiar craftsmanship of the wool, and the sculptural technique that the artist manages to exert very simply on an unconventional material. As we then move away to visit the other rooms, we note how its nearness to the window exalts the attention that Sheila Hicks places on the choice of colors in her sculptures, which allow her to operate also on a pictorial level, albeit a three-dimensional one.

Hence, the exhibition was created in close collaboration with the Galleria Massimo Minini in Brescia. And this choice was anything but a random one. It is rooted in the idea of the Borromeo family to collaborate with those elements that over recent decades have emerged as the points of excellence of the territory. The exhibition space of the Ala Scaligera in fact intends to act within a fabric made up of private spaces and institutions that throughout Lombardy have been operating on an international level for years, and which it intends to become part of as a natural extra-urban extension. Also for this reason it was decided to inaugurate during the Miart Fair period, with a view to underlining the desire and the need for the territory to think from within an ever stronger and more articulated system. The scene in which the Angera exhibition space will be placed is a very lively and diverse one, made up of places of various natures and settings, yet largely concentrated around the Milanese urban area. The location of the Ala Scaligera also makes it possible to strengthen cultural ties between Milan and the nearby Switzerland: one of the countries that has best managed to create a thriving arts scene over recent years. I like to recall that at the end of Lake Maggiore are the places where a giant figure such as that of Harald Szeemann lived and worked a great deal (for example with the projects on Monte Verit.). But in general, Lake Maggiore and the territories close to the Borromeo family may lay claim to a history full of ties with culture, above all for the very many writers who over the centuries have crossed these territories, stayed here, written about them and even drawn inspiration from them. I believe that all these elements may constitute fertile material on which to work over the years to come, and that the Ala Scaligera will prove itself to be a key factor in this process.

Español

Español