The calculated and precise sound installation of Agnieszka Polska creates an eerie sense of premonition throughout the haunted narrative. Harkening to the past – it foreshadows the future. Together, form and content coalesce into a parable of what is to come.

This critical and daring project proposes that all we hold certain is already past.

By Àngels Miralda | Images courtesy Hamburger Bahnhof

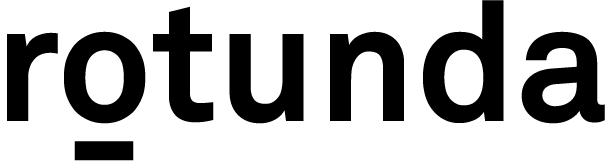

Agnieszka Polska’s The Demons Brain premiered at Berlin’s Hamburger Bahnhof on the 27th of September 2018 and runs through March of this year. Marking last year’s Nationalgalerie Prize-winner’s solo exhibition, Polska has developed a contemporary masterpiece that rethinks the medium of film by bringing space, sound, and time into its own web of narration. The traditionally ascribed format of linear temporality is transformed into a powerful proposal that shatters the regularity of time and abstracts it into a spatial and flat dimension. Through a narrative that takes us to a proto-capitalist enterprise in medieval Poland, our own contemporary position in society is rendered helpless among forces larger than our understanding. This critical and daring project proposes that all we hold certain is already past.

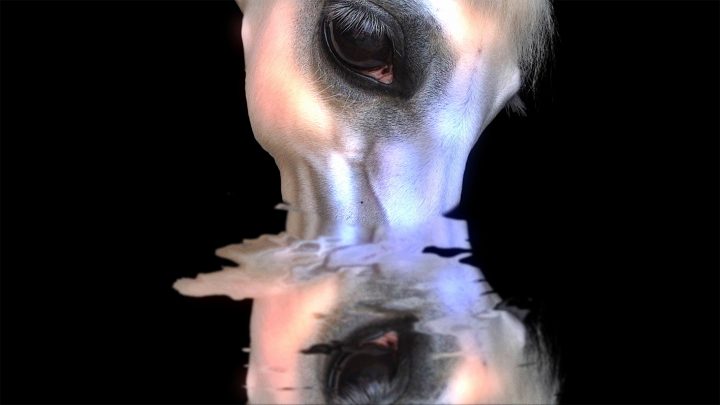

The Demon’s Brain develops previous formats of Monumental Film. Polska’s new piece adds an element of effortless pervasion of sound through space that sews together time with the rhythmic beat of a human heart and horse’s hooves. The structure of the film is environmental and embryonic, vitalizing the message through complementary form. The calculated and precise sound installation creates an eerie sense of premonition throughout the haunted narrative. Harkening to the past – it foreshadows the future. Together, form and content coalesce into a parable of what is to come.

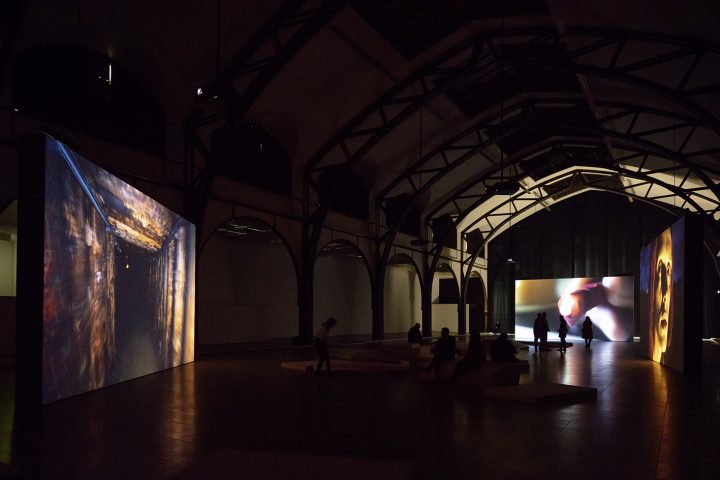

The setting is introduced before the film begins through a timeline on an exterior wall that greets visitors with information. A curious enterprise in Medieval Poland is described in which an overseer – Serafin – took over the management of salt mines in an early capitalist gest under the auspice of King Władysław III. The setting indicates that the social problems which we face today including labor exploitation, climate change, and political disenfranchisement stem from the transition to capitalism embodied by the supervisor and voiced by a demon. The narrative of the film places us firmly within a stagnant time that is defined by exploitation of human bodies and natural environments in opposition to modernist conceptions of progress and linear development. The central characters represent constituencies from powerless laborers, a cruel and senseless elite, and an animistic force with indifference towards good or evil – a sprite from the future, present and past. This Trilogy of characters begins a treatise on contemporary theology that observes our feelings of helplessness within an economic system which itself is helpless within nature.

Signifying the laboring class, a messenger is introduced on the first screen. The messenger looks fearfully at his master as he reveals his skill at horse riding and inability to read – a skill and deficiency both necessary for his employment. Unable to decipher the message, and unable to change the miserable situation of his surroundings, he is nothing more than a tool in a system of forced labor imposed by coercing power. As will be implied, his greatest power lies in the decision to stop playing his role – a negative process of recalcitrating duty. A metaphor for the position of the artist, the messenger has access to powerful individuals who wield the forces of capital, but he is unable to influence them or to understand their true position in the world.

The demon appears next. It appears when the messenger has lost all hope due to an accident of no fault of his own, and the condition of life manifests through the supernatural, a timeless, shapeless, omniscient specter. The narrative is symbolic of the condition of working people as the resource behind capitalist expansion, and a nihilistic sense of the pervasion of evil embedded in the texture of time. The flattening of time and fragmentation of narrative, even the particularly tragic setting of an economically and ecologically ravaged land, speak to the endless perpetuation of class struggle and its unavoidable succumbing to the next stage of life – a terrible world described by the demon in which “bodies consume coal, and sweat smells of oil.”

Yet, along with the narrative – form strikes a proposal that echoes the omnipotence of this marvelous hallucinogenic demon and creates a world with its own properties and physical laws. The film’s form puts at stake the very conventions of film by creating an arena of total immersion, continuous sound, and physical submersion into the narrative apparatus. If this space comes from any model, it could be a deep web – a nightmarish google dream in which objects intersect through association. Projected onto four screens in the Hamburger Bahnhof’s historic hall, the arrangement of screens provides an intuitive gesture of precedence – an expert navigation of space. Forces of intuition, premonition, and magical language push forward a mystical landscape of our near future and our distant past.

The immediateness of the screens’ visibility on first view contrasted with the delicate layering of sounds creates a narrative that goes backwards and forwards at once. The use of subliminal premonition weaves the narrative and endless time down a dark corridor of flatness which nonetheless reveals infinite permutations as the cycle completes and brings the viewer back to the first screen. The film engages with the fact that the barbary of history has not been overcome – it is seemingly an eternal condition emerging from an underlying hellish landscape. Repetition revolves in cyclical tides which return the format of society as a self-surveilled penitentiary and individual’s own smallness in the greatness of the world. The film shows the complex dynamics behind social change. It proposes that small anarchic actions are a microcosm of revolt that can easily break a mechanical chain. The call that emanates “it is not too late” is therefore directed at a collective entity – humanity in general if it wishes to outlive its demon child and overseer.

The demon is incomprehensible, it is only a fragment of itself that lives multi-dimensionally, jumping between universes. It is singularity, a hyper-object, mother earth, the trilogy, simultaneously as a product of humankind. It embodies everything we fear because it speaks of the reality which we live, and that which we are creating – it also reveals how easy it would be to cog the mechanism. Since time was flattened into an endless congruity, the idea of it being “too late” would be redundant. “It is not too late” asserts that something can be done just as Serafin once mysteriously appeared.

Español

Español