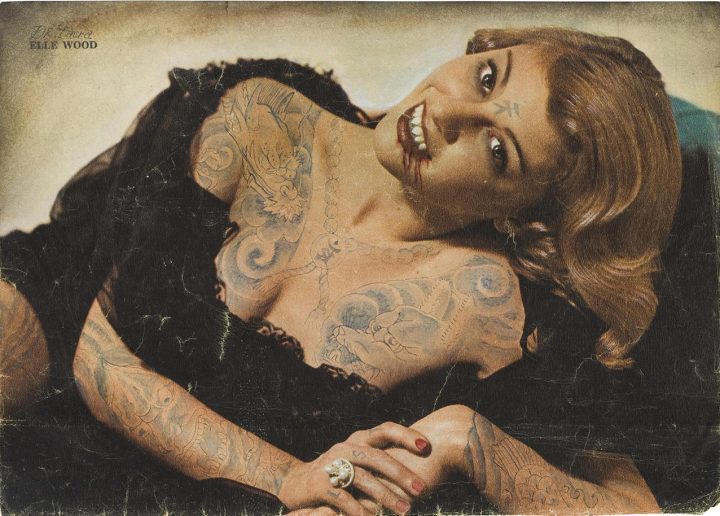

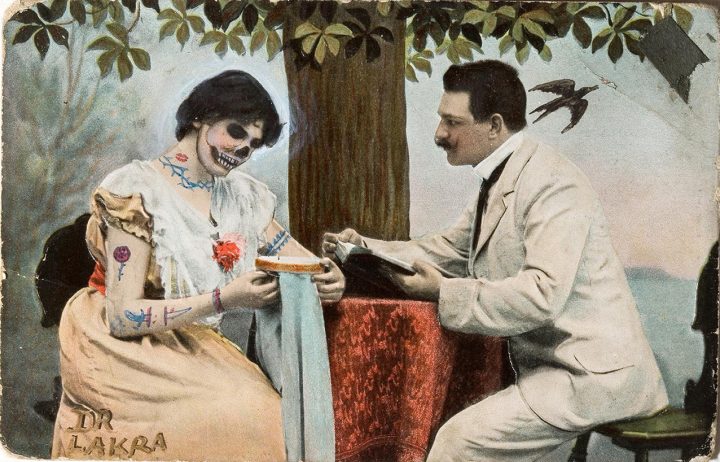

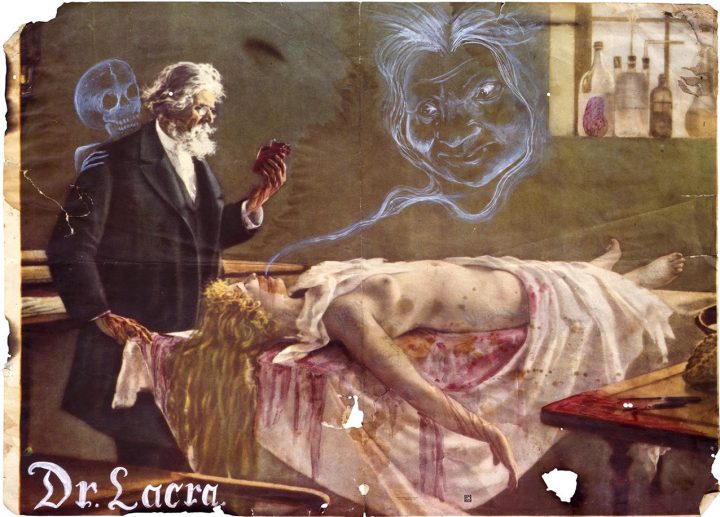

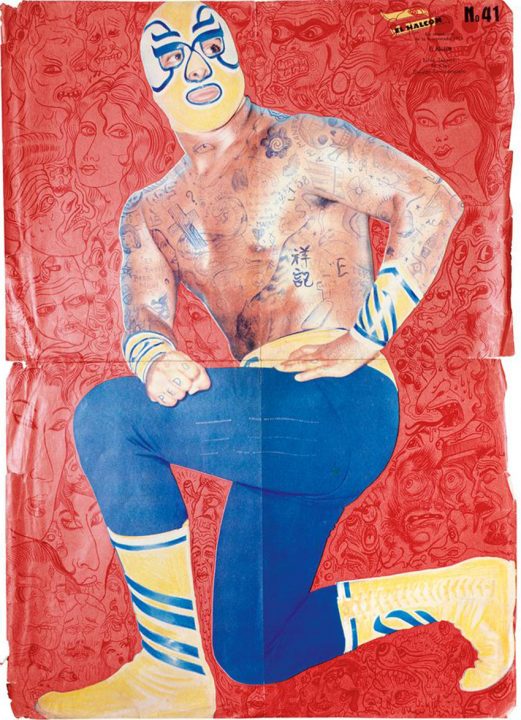

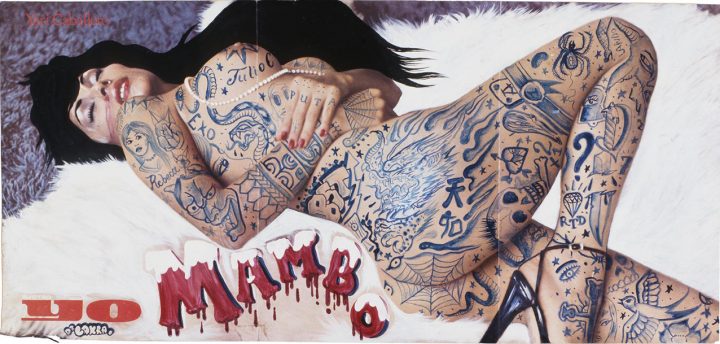

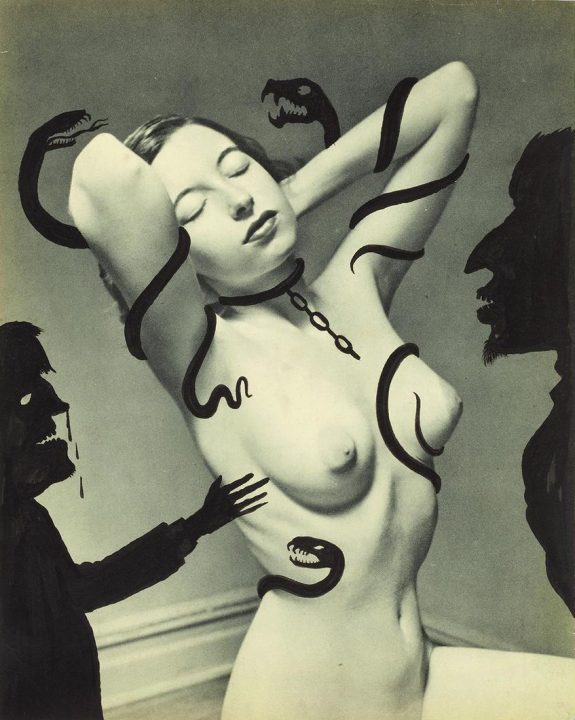

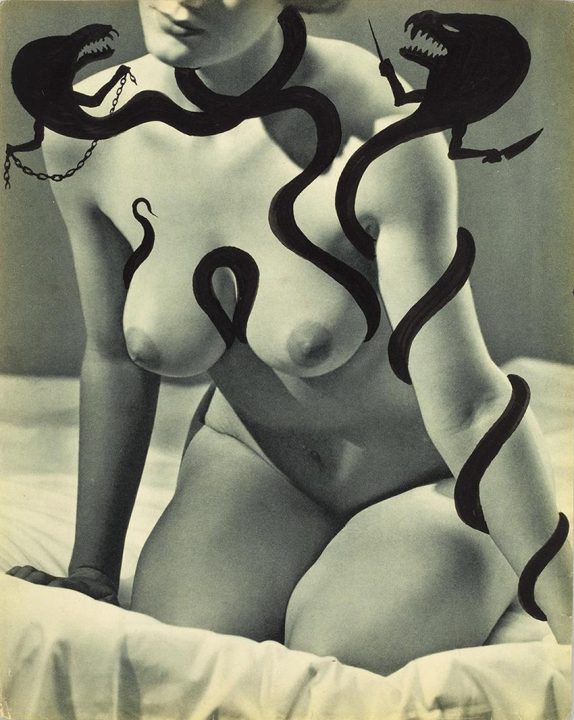

The Mexican artist Dr. Lakra or Jeronimo López is currently exhibiting his work for the first time in Peru at the Mario Testino Museum MATE. Within this context, we spoke to the artist who comes from the tattoo tradition, and that has mixed with the collection of different objects that are born of mythical narratives that coexist with a globalized imaginary, generating a work and a very particular visuality.

By Carolina Martínez Sánchez | Images courtesy of Mario Testino Museum MATE & kurimanzutto

Carolina Martínez: How does this opportunity arise to show your work for the first time in Peru through MATE?

Doctor Lakra: The Peruvian photographer Mario Testino, founder of the museum is a collector of my work, and it was through him that the invitation was managed.

CM: Being that this exhibition is the first one there, but at the same time your being one of the most known Latin American artists, under what criteria or feelings did you start to prepare the show? What or how do you expect your work to be understood in this context, and does it’s matter to you how your work is interpreted by someone else?

DL: The truth is that I have never been interested in taking the viewer’s hand to a specific place. I find it much more interesting that they lose themselves in their own conjectures and interpretations. This exhibition is the continuation of a series of exhibitions in which I have played with the sculpture, not only three-dimensional, but also with the sculpture as image. Many of the pieces of wax are made with objects found in Lima, as are the collages made with pieces of books that were also found in that city.

“I have never been interested in taking the viewer’s hand to a specific place. I find it much more interesting that they lose themselves in their own conjectures and interpretations.”

CM: Part of your training as an artist has been tattooing. What did you want to experience at the moment that you started with this? What aesthetic and cultural elements did you take to translate into this form and technique of drawing?

DL: I started painting in art studios before tattooing, for this reason is I already knew how to draw when I got closer to the tattoo. I got interested in this technique because of the socialization involved in the practice, although being honest, I actually knew very little of the tattoo. In 1988 I got my first tattoo and in that time in Mexico there was almost no information about it. It was much more intuitive my approach, did not expect or wanted anything.

“I like to create confusion, I am already too confused!”

CM: Taking certain formal manifestations and artistic practices from other cultures as well as from one’s own history but already passed, one could be bordering with the issue of not generating an immediate sensibility, turned into potential distancing, or even a postmodernist “re mythification” of myth. How do you work with these lines that even could lead to a confusion?

DL: I like to create confusion, I am already too confused!

CM: I imagine that your collecting is not only because of the work you do, you must also have a great personal fascination. What was the first thing you started collecting, and what are you interested today?

DL: I think the first thing I started collecting were comics and now I’m excited collecting LP’s on vinyls related to the tattoo, even if their own music does not interest me.

CM: I imagine you as a great collector of the imaginary, who re-assembles or reconstitutes them, with a consequent re-signification. What is the imaginary in Mexican culture that you see around you today? What is the imaginary housed behind your pieces, and where through them you could project your interpretation of this current narrative of Mexico?

DL: The imaginary in general is very globalized, and for this reason I don’t care or believe in nationalism or talking of the imaginary of a country. I think today I’m interested in finding common points and symbols that everyone understands, like the E.T. repeated in many of the sculptures.

CM: The elements of popular culture you mix with myth and historical traditions. You would also postulate that all the myths enclose one, being a “monomyth”. How do these contemporary elements become mythological? What is the common point that could lead to this unique, timeless myth?

DL: There is no specific point where they join, but rather many. The term “monomyth” that I use in my exposition was coined by Joseph Campell.

The elements of popular culture are also permeated with myths; the toys that children play with, the souvenirs that tourists buy, etc. All of that already being born from a myth, they don’t ‘mythify’ through the time.

“The imaginary in general is very globalized, and for this reason I don’t care or believe in nationalism or talking of the imaginary of a country. I think today I’m interested in finding common points and symbols that everyone understands.”

“Personally, I don’ try to rescue any traditions, nor use specific narratives. In the same sense, I have not developed a work based on Latin American traditions. I don’t think they are different from the occidental hegemonic axis.”

CM: It is said that no artistic practice is innocent or can be detached from it’s context. Is your work subordinate to a political biography – understanding that we are all political beings that act and interact within a cultural society, or do you try to detach to yourself from a visual and historical narrative, and try to carry the meaning of the elements of your artworks by their own immanent content?

DL: I don’t believe my work is subordinated to any political biography and the elements that I use already have with them a visual narrative of which they can’t be disconnected. Of course they could be meant when you put them together with other elements, but they still have an immanent content.

CM: Undoubtedly, the rescuing of Latin American traditions, both in their narratives, history and aesthetic manifestations is something that many artists are developing and investigating. For you is it a form of struggle against the occidental hegemonic axis, or is it a way of living together and putting oneself in the own place within a model of a transglobalization?

DL: Personally, I don’ try to rescue any traditions, nor use specific narratives. In the same sense, I have not developed a work based on Latin American traditions. I don’t think they are different from the occidental hegemonic axis. It’s the same bullshit.

CM: In this sense, how do you perceive and project the art of Mexico and Latin America, it’s practices and fundamentals?

DL: The artists who work in “this sense” don’t interest me in the least.

CM: In addition to your current sample in MATE, what projects are you working on today? What topics and elements of aesthetics have your attention today?

DL: I have an exhibition of the same series of “monomyth” in the Kate MacGarry Gallery in London on April 20th 2017, that keeps the aesthetic lines of my work.

Español

Español