“To me the only thing that has interested me since I was child, is that rude thing of the art”.

By Carolina Martínez Sánchez | B&W Images: Sebastián Mejía | Color Images: courtesy the artist

Castillo. Juan. There is a background behind him. From the dark times, those in which you could not go around saying what it was thought. From the times when you distrusted even of your shadow like the mothers who lived those days would say. From the times where there was a gag; real for some, implicit for others. That is where some insurrectional artistic collective emerges. Not so much, but a bit as a way for displacing the symbols, camouflaging the meanings. It seems to be that were more challenging the new formulations in the artistic practice that was mutating influenced by a vanguard scene that had nothing to do with painting or with a certain “tradition” -inherited from the first world obviously-.

It was about the disruption, something that the artist born in Antofagasta had lived and known since childhood through his grandfather who was painter and photographer, and considered useless because he could not get a job since he was communist.

His first exhibition was at age thirteen without knowing much about what was thing of selling, and that same day that the director of the symphony of Antofagasta, Joaquín Taulís bought all his works, he also experienced his first drunkenness. So, he began to live in an environment that helped a lot to creativity and relationships, growth and expansion:

“At that time, all of us interacted with each other, no matter the age; the discussion was very rewarding. I did not have adolescence, I was always just with old guys, I did not have a girlfriend either, and when I was seventeen, I came to Santiago to have a meeting with a girl. All this was a natural thing for me.”

With all this already in the body – and the spirit – Juan decides to study Architecture at the Universidad Católica de Valparaíso as a good alternative to Fine Arts, since his father did not allow it, and although it was a sort of second option under those circumstances, he met with a whole fascinating world, where those who forged this University, were still alive at that time.

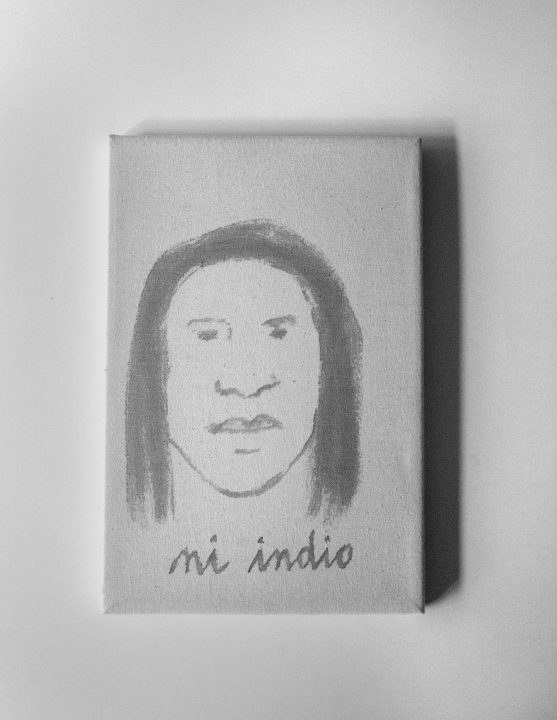

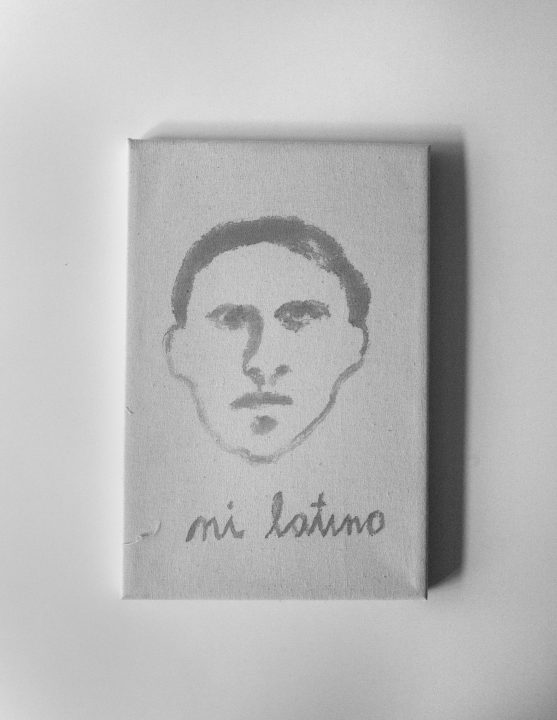

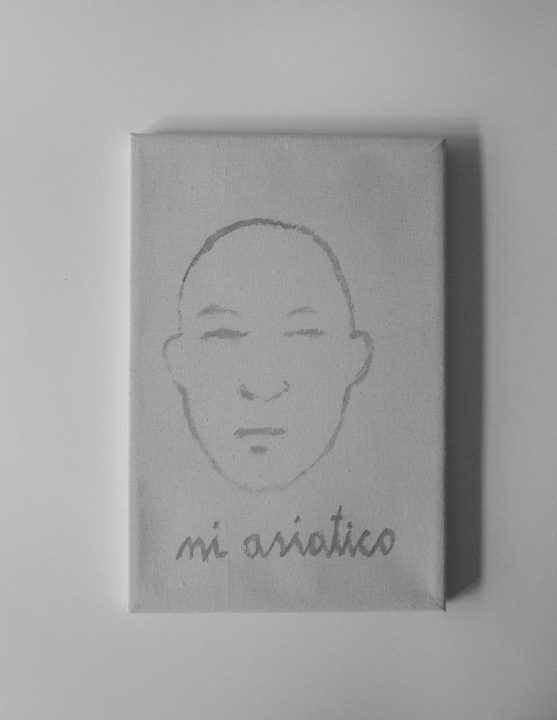

Faces and furrowed (mutated) symbols in the landscapes

For Juan Castillo, his first exile was when he moved from Antofagasta to Santiago. The culture and the landscapes so different, but his first and most intimate relationship is with the desert:

“If I feel anything like homeland, as a homeland, is the desert. I feel Chilean only when the Chilean football team plays.”

Anyway, he loves to live in a continuous moving, and he sees how many people of his generation living in Sweden or other countries long to return, in opposite way to what he wants. “If you miss so much, go away, it’s almost like an anguish for many.”

That homeland of landscapes he has shaped it in a certain way in a work that has been developing for many years: “El rostro es el paisaje” (The face is the landscape). He has always been fascinated by faces as unlimited crosses to achieve to what one can be. And that is the only homeland for him, oneself. And on the other hand, the landscape considered as an influence in our thinking way and feeling, and in that same sense is that the desert was so important. The beauty of that nothingness, just like silences in music.

To get rid of the concept of country, a construction that we have not done or chosen and that has easily led people to segregate the other, when in that exchange there can only be growth and movement.

“That fear of the other, when there is no univocal culture. That is not seeing how the things flow.”

For Juan it is only possible to think of life in that constant flow between individuals and a permanent construction of themselves, that inner and outer dynamism that drives away the fossilization of character. The encounter with the other is what feeds and makes possible his work, all those related visions.

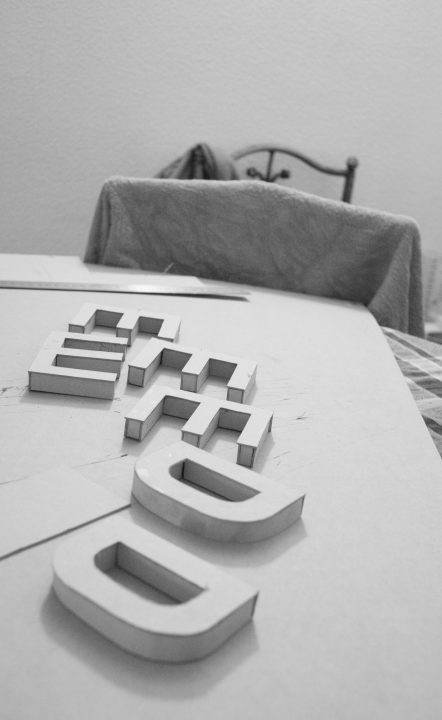

About visual strategies of C.A.D.A. On the fly or explicitly

As for many people, the arrival of the television to home marked Juan Castillo. Yes, probably the concern at twelve years was came from another encounter with the device; immediately filled with cloths, embroidery and figurines, almost an installation. What also captivated him, and in certain way influenced his beginnings with video, which unlike film, there was no dictatorship of the image, where is necessary to attend to what is happening at a certain time , or stay in front of this succession of images. You could be in front of the projected image, or simply change it, or turn it off. And from that same freedom with the image or the spectator, is that later the members of the C.A.D.A. group realized, and by the force that could be lay in the record itself, they started to consider the video as an independent artwork beyond the record of the other actions.

But what radically influenced and shaped his practice and thought -as for so many artists of that time- was the coup in Chile and its subsequent dictatorship. Juan recognizes that he was very lucky for his destiny, unlike many friends who disappeared or died. The same influence that made to him and other artist and intellectual friends, look for new forms and proposals for and from art, and above all for those meanings that are so hard to express, and those so opposed signifiers between the military apparatuses and politic and the people.

Before than the Colectivo Acciones de Arte emerged, the artist from Antofagasta had already started working with the also visual artist Lotty Rossenfeld, where one of their first actions was an intervention with images of homeless thrown in the streets of downtown in Santiago and then stuck in the trees of the Forestal Park. Then came “Por los derechos humanos” (For Human Rights) in the Church of San Francisco, and then in 1979, along with several other Chilean artists, the exhibition “Recreando a Goya” (Recreating Goya) took place at the Goethe Institut, where the inspiration was the painting “The executions on May 3rd”, being practically a quote to what was happening.

There they also join with Raúl Zurita and Diamela Eltit and the next day the C.A.D.A. was already configured, and after a month, the first artwork.

At the same time, other groups of artists and thinkers had also been formed, one was V.I.S.U.A.L. conformed by the poet and artist Ronald Kay, the plastic artist Eugenio Dittborn and the visual artist Catalina Parra; and in another one was Nelly Richard with Carlos Leppe and Carlos Altamirano. But the group formed in the Goethe was interested in the thinking of and from the art, not being able finding in those other speeches the intention of de declaring what was the Chilean situation, and that was what the C.A.D.A. wanted to do.

The problems and formal discussions of art and its speeches were of course an essential concern, but it would not have made sense without the interest of linking it with what was happening in Chile.

Castillo recognizes that he has never seen that art in contemporary times has really changed a society, but he does understand this as a sign. And in the exercise to reach the change and the formulation of statements was where the energy resided to produce the actions that were quite followed. Money was not enough for that and each one developed his/her individual work. Diamela was writing a novel (“Por la Patria”), Raúl published once the C.A.D.A . was formed, “Purgatorio”, his first book, Lotty was doing the interventions with the crosses on the pavement, and Juan was already working with his interventions of empty grounds.

Although some of the members of the collective had political militancy, the group was not an expression of any particular political party, which is why other more radical sectors treated them as petty bourgeois, blamed them for using televisions or for using a language that supposedly not all the audience could understand, a matter that for the group would immediately disqualify that audience; each way of approaching the works and each thinking fits, that is why there are thousands of artworks and possible interpretations.

“For me at least, I am very interested in ambiguous discourses. I believe that there can be a complexity and a possibility of many possible interpretations.”

After some years during the decade of the ’80s of using the streets to work with the collective, such as open museums spread around the city, Juan Castillo decided to emigrate.

The first leaving

The first solution to collect money was to exchange some of his works that were less commercial during those years, for some other ones of his friends such as Juan Dávila or Eugenio Dittborn and thus be able to sell them, but winning in 1982 the First Multiple Media Award of the III National Competition of Graphic with Ximena Prieto, with the work “Campos de Luz” (Fields of Light), meant the arrival of an unexpected money, avoiding the sale of these artworks and so he could do a trip that first would take him to Spain and then to France on the occasion of La Biennale Paris of 1983. After being in those two countries, he travels to Stockholm to be delighted with what is Sweden. The first time would be a good welcome that would not last long, after several months with several projects and work, comes a period of inactivity that led him to have other occupations.

Being political is not about politics

If all human beings are already political just because we are in relation to others, for the artist that political art that would have become fashionable in so many moments, for him it would be something like a conceptual invention of art critics and gallerists for selling something that really does not involves such content. That ‘political thing’ would not be in certain messages, but in certain attitudes that an artist may open as questions to society, but that is asking them to himself.

He assumes that he has many prejudices against this kind of art, where one can certainly take the risk of using in a bad or wrong way, certain social or political issues because they can cause a great and rapid media impact, and there is no any right – even if ethical or will- to use such situations, recognizing as an example of what he says, the Spanish artist Santiago Sierra.

Identities and images that are lost in the flow of time and the visual regime to building new narratives that exalt those lost individualities. Assigning faces and shapes to untold stories

That is why it is so basic for doing his narratives the contact and dialogue with others, formed by hundreds of interviews that often do not end in one piece, but is part of the ongoing process of knowing that other. For each project, he develops some kind of relationship with those who participate in them, either through photographs or stories, because each face is a map that obeys a mixture of things, happening in that friction the encounter with the identity. New formulations that open mysteries where there is not only one message, but many, where the body and mind can answer in other unexpected ways.

Español

Español