Community is what always takes place through others and for others.

Jean-Luc Nancy

By Francisca García | images courtesy the artits

Chilean artist Juan Castillo (Antofagasta,1952) left Chile in the early eighties, putting behind him the shared experiences with the Colectivo de Acciones de Arte (Action Art Collective), CADA, to wonder about different European cities until finally, he settles in Stockholm. After some decades of absence from the local scene, Castillo recently resumed visits to his home country, directly influencing the dissemination and establishment of his work on a national and international level through the proliferation of texts and curatorial work. In this sense, one might wager to propose that his name will soon become part of a certain expanded canon of visual arts, in which interdisciplinary research and, in general, all sorts of transgressions against ideas of artwork, author and place, at least as we understood them in a context of modernity, are valued. As part of his own course of transgressions, the artist has adopted the name Huacherias, for a series of exhibitions that span the years between 2015 to 2017.

If the so-called culturalist shift in art and literature has considered it urgent to grant visibility to different practices, creative processes and marginal imaginaries that have historically been excluded from media discourse and from the canonized logic validated until recently by institutions, Castillo’s project, on its own, has pursued a renovation of its modes of making in terms of the production of spaces of collective subjectivity and collaborative logic that displace the traditional notion of authorship. In a way, this display of memories, a part of the actions carried out by Castillo, complements and magnifies what has been presented to us as the official story, with all of its missing spaces, understatements, and arbitrariness. Similarly to how he rehearsed it during the time working with CADA, in the Chile of the late seventies, Castillo’s recent work searches incessantly for the possibility of expression and interaction of the personal memories and testimonies of common people, thus weaving an artistic body of work associated to an uprooted community. This corresponds to a sense of community that does not coincide with how it was conceptualized in the past, exclusively defined by common linguistic and territorial spaces. This heterogeneous social dimension has been projected onto a type of unclassifiable art, that resists any label and flows from various approaches: conversation, archaeology, writing, drawing and gathering. In the following text I will support an argument based on various perspectives of this “culturalist shift”, not only in an attempt to squeeze potential meanings out of Castillo’s body of work, but also to think and learn through it about new ways to come together and name each other, of speaking and even living together, as political approaches to a current cultural scenario that is defined by movement and a general lack of fixed localization.

Nevertheless, some questions escape us towards infinity once we confirm this expansion of the frontiers between living and speaking, of living together and naming ourselves. Our inherited dictionary becomes useless in relaying a reality which actually proves to be open and expanded. Which words and concepts can we rely on, in the face of these new realities and communities? How could it possibly become unproductive to insist on the linguistic archive that has pursued generalization, which is always abstract? I corroborate over and again that the linguistic framework we have inherited from a logocentric and universalist logic is inadequate to name current plurality, let alone in interaction, if only to deactivate it. The appearance of these communities, usually referred to as nomadic, configured from the experiences of art and literature, challenge me to state questions that often lack answers and refresh the ways in which we express ourselves.

I will rescue the invented term huacherias, not only to describe the artistic installations presented by Castillo in different art spaces under the same title but also because it seems that this odd and improper word endows a singular artistic methodology, based on the exchange of experiences and memories, with a name. And as a hypothesis, I want to think that these huacherias describe a contemporary poetic that proposes formulas to mediate coexistence, not just multicultural coexistence, but all types of pluralities (beginning with his own unclassifiable body of work). A premise to help us understand this methodological strength, would be to heed to the great contradiction that has defined globalization for centuries: understood on the one hand as a context characterized by the free flow of information and goods on a global scale, while on the other as the source of tensions resulting from the increase in imposed barriers and limitations to migration between countries, of people and identities that are considered to be outside the norm.

Since the second half of the last century, subaltern studies have been concerned, academically, with the recovery and restitution of alternative practices and memories of groups that have been historically silenced and marginalized by official logic. I propose that the negation of the Other is part of the ethics of this perspective. The Other in power, the Other-empire, the Other-State, the Other-institution. From this point of view, it would seem that the subaltern perspective creates a continuation of the logic of thought based on rivalries or polarities to understand the cultural scenario in which we move. In objection, I would like to think that the culturalism that my interpretation stands for, is enriched by a liquid/fluid orientation: huacherias as an in-between space or intermediate space in which differences and singularities, languages, desires and dreams of people and collectives coexist, beyond a place of social and cultural origin. A utopian force rests over this proposal, perhaps the utopia that eventually motivates communities of all sorts, born as hybrids from and within reality itself. Invoking philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, I understand that Castillo’s project is moved by the desire of permanent exchange and displacement originating from and reaching towards the Other, thus configuring a fluid zone of acceptance and coexistence that reaches beyond the hierarchies institutionalized by art and culture.

Such a proposal also carries with it a series of risks. Therefore, the closing question must be: what can be done to recover and activate these improper words, while avoiding their becoming fixed by the institutional —and academic— apparatus and its devouring capacity to assimilate common and heterogeneous experiences, thus institutionalizing them and reducing their force as critiques? Less ‘concepts’ and more ‘idea-forces’, is what we, myself and Castillo, have concluded, convinced that language is generated within experience and thus, is in a state of constant movement and transformation. From this vantage point, words do not affix realities, nor do they contribute with definitions, at least not the words that interest us in our dialogue. Words are but traces of lived experiences and as such, rooted in specific moments. Therefore, huacherias is born as an idea-force, to the extent that it is not a category that refers exclusively to the period between 2015-2017, but a cyclic force that accompanies our dialogue. Idea-forces are defined by their fluidity, they are picked up, then laid to rest; they disappear to later reemerge, in a very different form, “as poetic texts”, Castillo points out, that are “a permanent supply of meaning”.

About the wakcha subversion

I had another dream that surpasses it, and not only did that dream

become reality, it also doubled itself, their names are Martina and Paula.

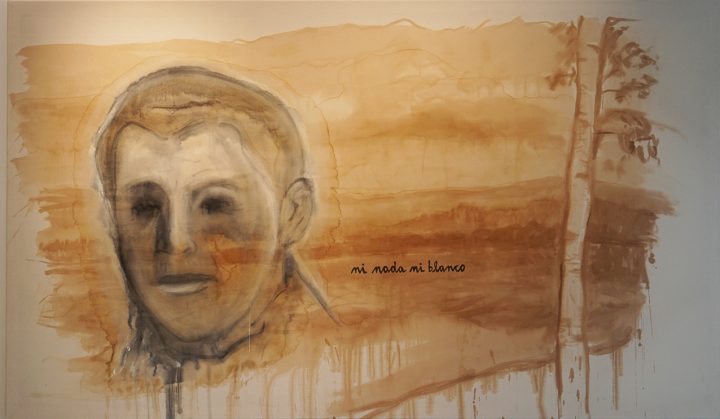

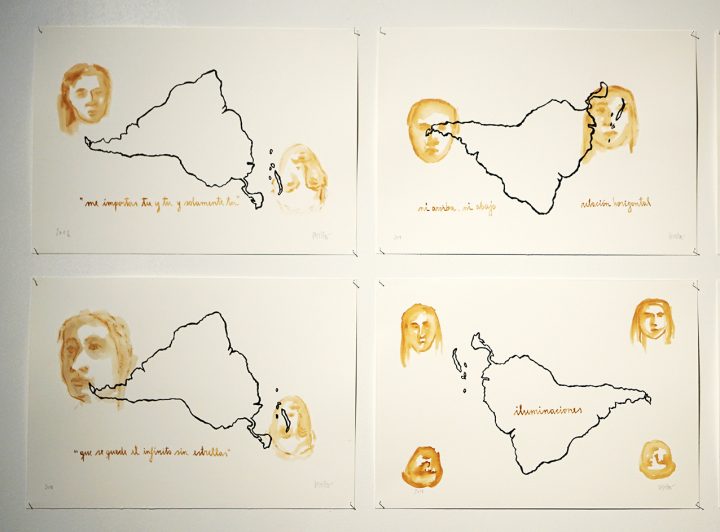

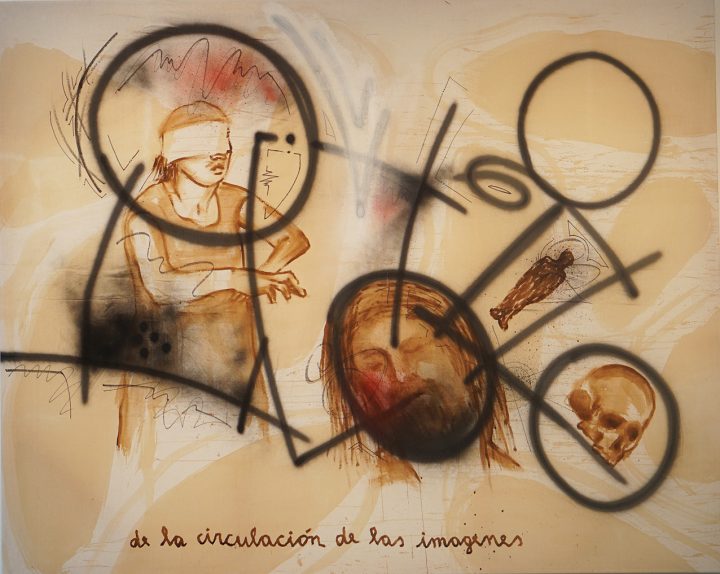

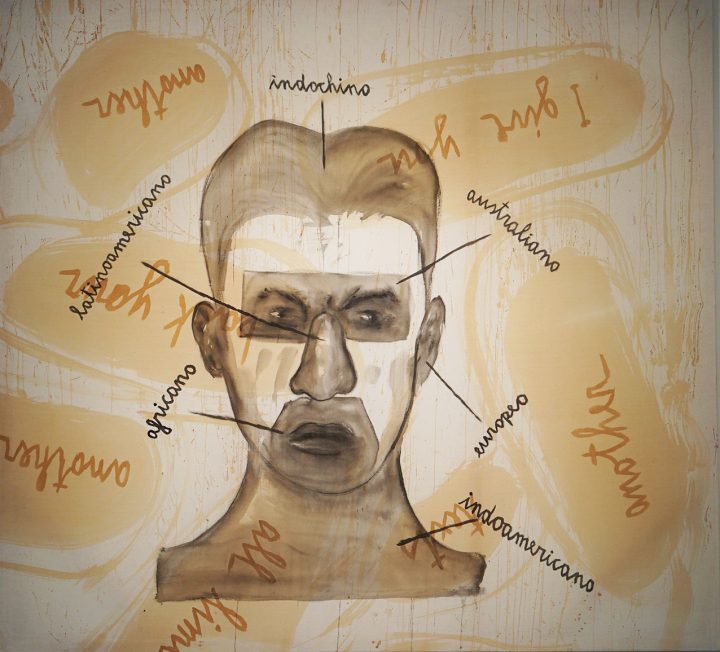

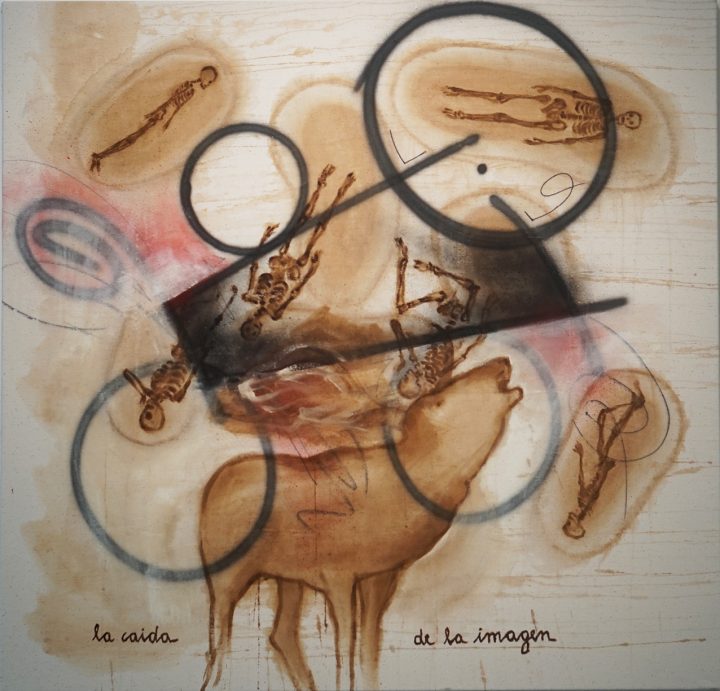

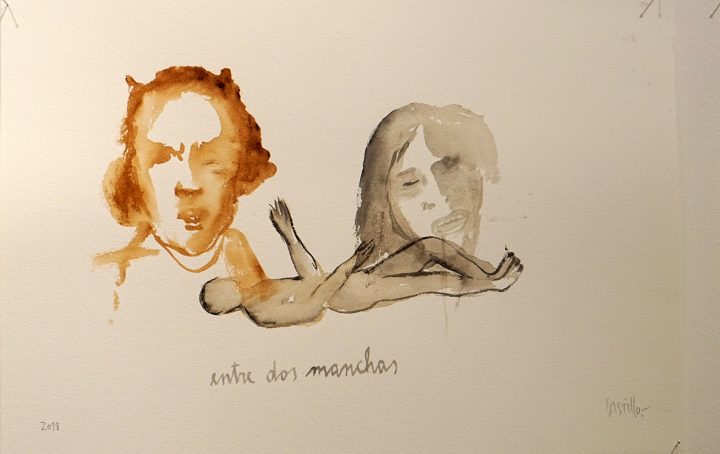

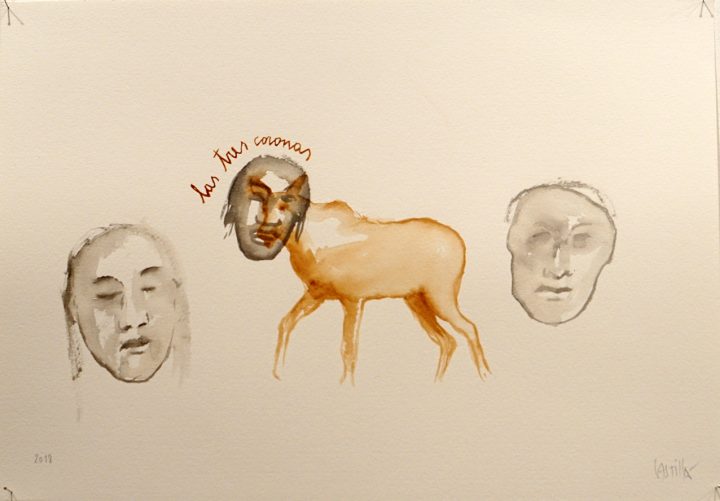

In Galeria Panam, an independent art space, located in the center of Santiago, Huacherias by Juan Castillo was exhibited in March 2016. Among the many elements comprising the show, a series of portraits of unknown faces were displayed on the walls. These medium scale portraits were made using tea as a pigment and they include abstract symbols and handwritten texts by the artist.

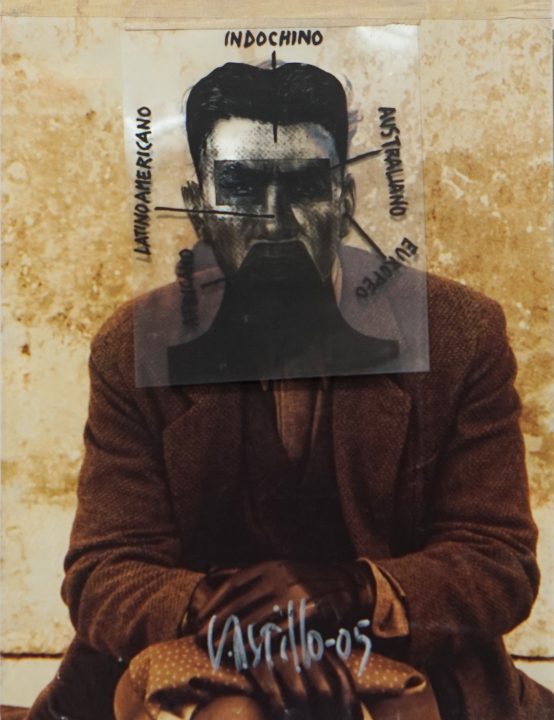

At first glance, there is no direct relation between image and text in them. Each narrative —written and visual— contributes with its own complementary meaning: while the texts describe desires and dreams of specific, common and ordinary, people the amorphous and sometimes androgynous stroke of the faces, might seem to allude to the idea of race and of predominant cultural stereotypes. In addition to the written testimonies about the faces, big and odd dotted line shapes overlap them, as if they were fingerprints intended to identify the specific testimonies, and perhaps also allude to the arbitrary control methods exerted by customs authorities over the identities that cross over borders. This last representation is set in a dialogue with a fourth element on the lower side of each drawing: an additional handwritten inscription, using tea, that makes an irony about cultural stereotypes through a double negation. In this case the face of a black man is accompanied by “Not African, nor anything”; a Chilean with “Neither anything, nor Chilean”; an indigenous with “Neither anything, nor Indian” and so on: “Neither Asia, nor far away”, “Neither black, nor Africa”, “Not new, not old”.

The many portraits, displayed on the walls of Panam, populate the exhibition space with an anonymous and desiring crowd of people from whom we know no names or surnames, nor their places of residence, but we do know their testimonies rooted in their daily lives. The visitors to the show became part of this anonymous collective, insofar the portraits invite to participation. The written testimonies allow the spectator to access a subjectivity and particular life experience but find themselves hampered by the idea of normalized and normalizing societies, represented in the fingerprints and the stereotyped faces of races and nations.

“The word is a condensation of infinite experience”, Juan Castillo states, “the condensation of a whole history, of a long experience […] Thus, behind each word stands, not just the word itself, but human history. All experience is condensed in it. Each invented word is a poem”.

The double negation in relation to the portrait’s identities —neither…, nor…—, seems to apply an emancipatory function: it develops a sense of cultural diversity that cannot be synthesized in one category, one word, one single ethnic trait, one skin color, one single language. The exercise tunes in with the multicultural turn, the idea of a melting pot and “hybrid cultures” promoted by globalization. “I will send you the text that I have written for the catalog to be published in the Los Angeles biennial… about the Huacherias project, almost an invented word, stemming naturally from huacho, but in its liberating sense, not its victimizing. The Huacho as someone who is setting himself free from former ties, one of them being his constructed identity, which addresses, from the homeland, those who we believe we are. Huacherias is something that is always being constructed, like the animitas in the Chilean North, open works. One is not, one is becoming….”.

Both Chilean historian Gabriel Salazar and Anthropologist Sonia Montecino have developed these studies from many perspectives that take charge of the Latin American huacho subject. Of Quechua origin “wak’o and from it, huak’cho”, this word defined by Salazar as “the animal that has left his herd” or also as “dispossessed subjects”, in Chile —also written with the letter ‘g’—, went from identifying illegitimate children, subjects deprived of their ancestry or genealogy, and indirectly and derisively the state of “single mother”, who had to take care of supporting her children from a position of social marginalization. From Salazar and Montecino’s viewpoint, the guacho will always involve a deficiency, a lack of something and precisely that state of orphanhood constituted the foundation of colonial societies in Hispanic America and the motor in the development of racial hybridity: “The Spanish had relations with indigenous women, but expected to marry Spanish women once they returned to the Peninsula”, writes Salazar.

The Quecha origin of huacho, swiftly refers us in literature history to José María Arguedas (1911-1969), an Andean huacho. In Argueda’s own life experience, as a mixed-race subject, ethnologist, translator, novelist in Spanish and poet in Quechua, bequeaths us with another vision of the huacho, different from the one defended by Chilean thinkers. In Argueda’s case, his literary legacy involves both an incorporation of Peruvian literature to a universal canon, his between-worlds experience relativized the meaning of orphanhood and inaugurated an emancipatory and libertarian process according to his own testimony. Puertorican author Mercedes López-Baralt remembers: “That Arguedas saw himself as a wakcha can be verified in his famous intervention of 1965 from the First Encounter of Peruvian Authors in Arequipa, in which he confesses to being the “making of his stepmother”. In this moving confession, Arguedas maintains that his stepmother, by pushing him aside and into the kitchen, despising him, did him the huge favor of introducing him to the affective indigenous world”.

Arguedas generates this semantic displacement as he gets to know and reflect about the original connotations of the term huacho: “Indians […] divide people into two categories. Those who possess riches, be they land or animals, are people; but he who possess nothing, not even animals, is huak’cho. The translation given to this term in Spanish is orphan. It is the closest term because orphanhood implies, not only a condition of material poverty but also a mood, of loneliness, abandonment, of not having who to go to”. The Peruvian writer transits from a “national orphanhood” towards a cultural liberation that displays many kinships, which in his case are expressed in the use of different languages for his narrative and poetic work, and for the cultural mediation and translation between the worlds through which he moves. The transformation in the state of being huacho, proposed by him, one might say in both his “life and work”, established an antecedent in an extensive itinerary of reflection about the identity of hybridization in the Latin American continent at the moment in which he was writing, the mid 20th century.

At least fifty years after Argueda’s confession in Arequipa, Castillo updates this same thought itinerary with his visual, linguistic and performative project. The artist abandoned his country in his youth and during his experience of migration he concentrated his attention in the problem of identity and also, in the acknowledgment of indigenous identity, understood not as an original root but as an active/current component of trans-culturalized societies on a global scale. Such recognition brings him to working with these indigenous languages, secret languages subjected to the permanent threat of extinction. In the artist’s installations, these secret languages interact with colonial or European languages.

Castillo’s term, huacherias, seeks to recognize in each subject the huacho that simultaneously all of us and none of us are, in order to break the idea of fixed identities and to dismantle the allegiance between identity and nation, between nationality and birth. Huacheria, as an invented word alien to any dictionary, grants, through its suffix “-ia”, a certain dignity to the huacho subject, and it names an emancipatory power that amplifies these “free” children, independent from an origin, in terms of family as well as of colonial and national ties. Similarly to Arguedas, here the suffix reverses the value of traditional semantics, from a victim to an agent, by appropriating the derisive concepts of the colonizer and turning their meaning, reversing the connotation, as an act of agency and emancipation from language itself: a query into how to name oneself and how to name one’s own practices, a type of action from language and enunciation.

Reuniting the disconnected

“My most important dream is that the world’s inequalities be corrected.”

Huacherias describe multi-directional voyages and encounters with peoples of different nationalities in a transatlantic dimension. Just as Juan Castillo’s work pierces through media and disciplines, his biography also traverses geographic contexts: he was born in the city of Antofagasta and lived most of his childhood years in the saltpeter mine Pedro de Valdivia; later he moved to Valparaiso where he studied architecture, and then to Santiago where he became part of the printing workshop of Eduardo Vilches at the Universidad Católica; in 1982 he moved from Santiago to Europe, joining the increasing ranks of forcibly or voluntarily expatriated Latin American artists and intellectuals, product of the oppressive and crushing local context imposed by dictatorships in the region; in 1986 he finally settled in Sweden, a fixed place of residence that allowed him, years later, sporadic visits to Chile for the realization of new alliances and projects.

Travel isn’t just a biographic element. Constant changes of place enable a conscience of movement that permeates the production of this art project, thus constituting in itself a methodology of knowledge and research, of encounters and dialogues, of gathering and interviewing. “I am interested in approaching, connecting with others, it is my base, my nourishment, I am interested in ethnography, journalism, but I am not trained in those professions, therefore the dialogue that I attempt to establish does not set forth from them, but from the empathy created through coexisting, I go and settle in the places where I will make interviews, I talk about many things with the interviewees, they know about my work, they know that I want to ask them things, we talk about it and, here the beauty begins, an answer starts to become, creativity arises, based on their experiences, of course”, Castillo writes in an email to me in October 2015.

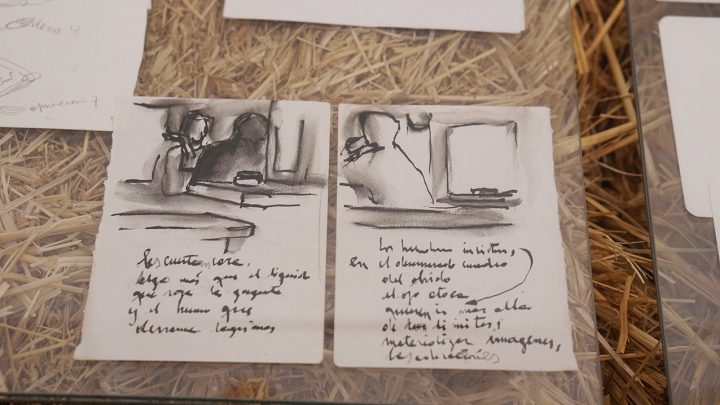

The gathering of heterogeneous life stories that drive huacherias takes place throughout brief stays of the artist in places where he settles down in order to chat with groups of inhabitants. Conversation is key to what is later exhibited, adapting to a diversity of techniques: in the case of the exhibition at Panam gallery it was calligraphy, drawings, printing and video. The voyage in itself weaves together people and voices reunited around the same questions. Permanent interaction with people and places, pushed this project to the realization of a participative work. In this sense, the articulating axis is the continuous encouragement of encounters and of bringing people together, whose dialogues, memories and words constitute a collective archive upon which subjectivities, voices, experiences are built, together with their images and desires.

In the case of the Panam exhibition, these huacherias, unfolded based on a simple question: what do you dream of?. The question was addressed to Bolivians who reside in La Paz. In their open answers, devoid of a determinate form —common to the format of conversation—, these people respond producing a collective memory space characterized by its liminality, between desire and rejection, presence and absence, the possible and the desired; as the notion of ‘dream’ awakens answers in the interviewees located in the fields of the oneiric and also in the areas of discontentment with the body.

These types of simple, general questions, such as in the case of “what do you dream of?” —which in other projects transform into “what does homeland mean to you?” or also “what does art mean to you?”— characterize Castillo’s many artistic interventions, carried out in the many places in the world in which he works. These are questions which unravel a series of experiences and affective and participative processes, which link voices and groups that do not necessarily share a common language, territory or culture.

At the bottom of experience, one concern becomes evident: to recognize creative human capacity, awaken a certain sensibility and to broaden everyone´s consciousness, well beyond the daily routines; to expand the horizon of questions and thoughts and encourage relations among aspects of life which stand far apart, to disassemble naturalized realities. All of these exercises of consciousness are meant to encourage the creative, in other words, the human. The power of these efforts towards acknowledgment of singularities, traces a path from art towards the social world, between the art world and the non-art world. The act of valuing particular subjectivities of each life’s itinerary has something to do with how Castillo acknowledges the common people with whom he dialogues, to him they are extraordinary characters. Yet above all, this gesture evidences Castillo’s own comprehension of politics in association with art in its possibilities.

The coexistence of times

“I repeatedly remember having dreamed that I was part of the conquest of

America, in the same group as Aguirre.”

At Panam Gallery, huacherias establishes a relationship between writing and materiality that destabilizes historic time’s linearity. Although Castillo was born in the city of Antofagasta, 1.300 km north of Santiago, he spent his childhood years at the offices of saltpeter mine Pedro de Valdivia, right in the middle of the Atacama Desert. Saltpeter was responsible for configuring a space of tensions of all sorts, based on imperial, national and cultural sovereignties, which gave a name to the territory: the “pampa calichera”. A concentration of modernity in the middle of the desert, crossroads and contact point, from 1930 onward, the economy of saltpeter articulated a multi-ethnic and multinational community. Men and women arrived there looking for work and opportunities, a “new life”, paradoxically in the planet’s most arid geography. The nationalities of the workers in this context was closely associated to the specific labor that they carried out in the offices: most of the owners, qualified labor and employees, were European, among them mostly English, Italian and German; the hard labor workers were Chilean, Peruvian, Bolivian and Chinese. Beyond languages and nationalities, saltpeter also wove a tight-knit between mining, social and indigenous history. Nevertheless, it is assumed that the latter, indigenous peoples, were not considered to be “workers”, and thus one should add that this story remains to be written.

“The tea is from my childhood in the saltpeter mines. There was this fantastic tea that they gave the poor people of the mine [laughs]. And this memory has stayed by me […] I began to slowly stop and look at the tea stains… I have been working many years with tea as a pigment”, states Castillo in an interview for one of his exhibitions in 2012. In the rooms of Panam gallery, tea is used to draw the series of faces and the footnotes that dialogue with the images. Most importantly, the use of tea is presented as an overlapped memory exercise, based on the presence of a materiality which carries with it an accumulation of experiences in time: colonial supplies and their distribution, the English colonial world and the exploitation of the Southern Hemisphere, miners´ struggle, survival in the desert, etc. Thus, childhood or family memories overlap with collective memories. But in contrast to traditional memory studies, always motivated by the desire of retroactive acknowledgment, huacherias puts this materiality to work according to current times and their own problems, in other words, huacherias effectively visits the past but does not remain there, in exchange it returns to respond or confront current problems. The singularity of this operation of memory is that it works forward, in a prospective manner: Castillo transfers the powerful memories of the mine, with their remote experiences of struggle and coexistence, to open today’s channels of expression and communication for anonymous subjects —today´s migrants are projected onto yesterday’s workers—, with their dreams and desires of an extraordinary life. Thus, tea materializes these dreams and desires. “The fact that these people who are habituated to listening to the discourses of others, listen to themselves and, furthermore, are interested in listening to themselves. This is where, in my opinion, we find subversion, in them, not in my “messages” and this relates to a very ancient idea with which I worked during many years, from the seventies to this day: “I return your image”

These narratives, that unfold in each one of the huacherias, become transcribed in handwritten calligraphies. As declared in a different context by Chilean philosopher Sergio Rojas, these calligraphies release a fragility, proper to memory in relation to History: “as an imprint of speech, in delicate proximity to the subjectivity that uttered them on a day other than today”. From this perspective, Castillo operates as a body that simply mediates between the dreams of anonymous people and the materialization, through the use of tea, of collective memory. Therefore, the word becomes image in the same moment of its imprint, which is a condensation or accumulation of memory, knowledge and lived experience in time.

Español

Español