In one of his last works, Javier Gonzalez Pesce divests from the desire of disguising vulnerability towards love, and rather submerges himself in the exploration of it, where a romantic imagery and a destructive methodology unfolds “Being so beautiful (does not) give you the right to destroy”. We spoke to the artist about the process of this piece, his own inspirations, and his journey and current scene.

Text & interview: Carolina Martinez Sanchez | Images: Emilio Marin | Translation and special thanks to: Ana Rosa Ibañez

Maybe it is that our exquisite vulnerability wants to stay always in disguise; not wanting to acknowledge the feelings or ideas that make our blood run. Being always ready to hide under a much studied rationality.

In one of his last works, Javier Gonzalez Pesce divests from the desire of disguising vulnerability towards love, and rather submerges himself in the exploration of it, where a romantic imagery and a destructive methodology unfolds “Being so beautiful does not give you the right to destroy”.

The show took place at the Visual Arts Museum, after obtaining the first place award at the VII Young Art Contest MAVI-Minera Escondida. He puts it together from a very un-recurrent topic in the arts, where love seems to have little leadership in the outcome of men and the world; and where more conjectural themes of the socio-cultural paradigms are the ones that have shaped the directives of contemporary art.

The arising of this piece and how it relates to the topic of love, didn’t come without questioning, as much in the discipline and in Javier himself, from certain criticism and frictions that the artist had been manifesting from his academic formation. The school where he became an artist, ARCIS, in a way (or many ways) soaked through an ideology that manifested in his early work. The suggestion of making political statements through the artworks and materials were almost a gravitational mandate for and within society.

The political and social context of a certain section of the country’s history was without a doubt a propitious place for political art, and a whole circle was trying to evidence that moment, through dialogues that discussed the contemporary conflicts. The group of outpost Chilean art, like the C.A.D.A. collective incited to follow the directives towards a political kind of art.

“ There was a lot happening. The social and political environment from the ‘70s and ‘80s demanded a critical perspective from the artists, and that gestated a cultural movement that was very attentive to the country’s situation. Now, when I started studying, I was very ignorant towards this local artistic background, my motifs to study art were very superficial: I was good at drawing, I had never propounded myself to make political art… It wasn’t until college that I became fascinated by the social and committed possibility of the arts.”

But this distinctly political restlessness started to shift when he felt like he didn’t have the vocation to carry a message, unlike many artists of the past generation or even his own, who still rather hide in the “hyper-intellectual philosophy” of art. Going even further, it’s not just the interest of running in some other highway but, referring to the artist Mark Manders, the wish of not making political art is given as it relates to the state of matters. If the way of how matters are going shifts to another direction, it becomes necessary to re-think the art that’s coming from that place, which can be very obvious sometimes.

“The work of Santiago Sierra is interesting as in it administrates political and social issues in a formal structure that is artistic. When he blocks an avenue in Mexico City by using a truck for example, he is doing a very subversive operation, but through tremendously clever geometrical observation. In the art that interests me, formal (or artistic) cunnings with conceptual commitments, generating poetical, subversive and artistic complicities; they all coexist.”

In this sense, art can be used to open a blind spot of intelligence, an open space conceived by Heidegger as a “clearing”, where the specific way of organizing materials and information may be quite surprising, and would make possible to witness the world that is presented and re-presented by the piece.

Like this, the formal administration of certain contents started to occupy the structure from which Javier Gonzalez projects each of his cycles, and organization became a fundamental piece for their development. This doesn’t mean at all that they lack in content:

“There is no doubt that while art is honest, it will have a political vocation declared in a non-expressly way. Art is a production method that communicates in very particular ways, the total abstraction or even the most literal art contain messages, and is under this logic where I appreciate honesty. If the artist manages to establish a committed contact with his environment, is very likely that he will be transmitting a reflection of this in his work, which is a political act in itself. Context generates subjects.”

The message contained in the artist pieces would be conceived from a visual scene; with a shift to smoldering information and symptoms that were traces of the discussed topics.

To think where is the piece erected, the “political possibility” makes the difference, is it conceived from politics or art. Politics would never disappear for Javier; they would continue to linger in that space of self-indetermination, appearing in a most natural way when the piece manages to be well articulated. He works over this articulation of elements and information. His problems refer to the formality, and if we wanted to crumble his work, we would discover mere relations within a structure:

“My work has always developed around the administration of this formal issue. For me, the main problems of my production are structural, which also open a profitable gap for signification, where the themes arouse. In a way, I use my formal discoveries as a structure or support for conceptual issues. Both things can be kept completely separate until they become an art piece.”

The conceptual boundary is driven into crisis, where the operation between inner and outer structure of the projected piece catalyzes a certain discourse and holds within a determined behavior.

When Javier wins the first place of the contest, and “Being so beautiful does not give you the right to destroy” starts to gestate, the “intellectual vocation” ’s ghost became a sort of rebellion upon his own sophistication and depuration, and love appears as the subject around which the piece is going to develop. It was also the subject for the piece that won the contest. Love, in the words of the artist, is not a foolish topic; but unexplored and inexperienced. And so, the romantic Italian musicians from the ‘70s and ‘80s became the main referents in this process; not the traditional philosophy nor the online love philosophy courses answered the questions that Javier was asking to put together the argument for the exhibition.

The dynamic of human relations as a structure captured his attention, the dialectic in which they are given:

“I have many friends that enjoy me talking about love and giving them advices. I think I’m good at understanding human relations. Maybe not, but I do like to listen, and it seems to me that I say stuff that other people like, or that make sense to them.”

But it was over the violent imagery of love where the formal issue and content administration unfold the structural approach of the developed pieces. Heartbreak becomes its engine, and destruction its mechanics.

Having the MAVI museum to his complete disposition, this production didn’t seem like an easy task. He didn’t have many days for the montage and during his visits to the venue he spent his time measuring. The process of conceptualizing was surprisingly fast: just one night, starting from his personal request that was to connect both floors of the museum. It was an alert day and full of creative epiphanies, where once again the structural issue was the first matter for building “Being so beautiful does not give you the right to destroy”. Based on this formal question, Javier had already developed some proposals, and he returned to them that night. The structures were planned and the subject that he wanted to work with was installed very clearly.

Pre-production then, did not meant hours of dedication being the assembling the more time-demanding because there was a lot of build-in-place to carry out.

Some of them functioned from sculptural conflicts that manifested often and in repetition. A body or unit doesn’t need to behave in an equivalent manner the whole time; it’s the morph analogies the ones that administrate this appearance on things and the symbols that coexist within them. At the beginning the perception of the world can be quite a-morph.

”The shape of things, material and structure-wise, is very different from experience; later, with time and reason criteria they fit into a logic. What humanity has done really, is inventing a treaty to understand reality. I turn to the possibility of madness, of not coping with this treaty, and inventing new ones for perceptions, realities and senses.”

The exhibition is articulated by different pieces that act from a structural dialogue, and the shape and content administration that nurture the work of Javier Gonzalez Pesce. Many of the also operate from destruction; in the moment itself – pieces that generate and accumulates material waste – and also some that gradually lose their matter and shape.

The piece “B.E.” (Each piece carries the initials of some of the most important characters of the artist’s love history) represents the love phenomena quite successfully. The subtle but weary violence, and strange selfishness described in Plato’s Phaedo.

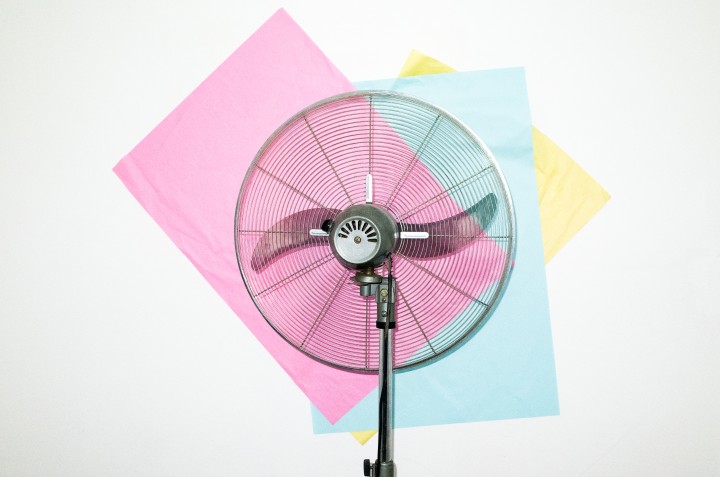

Sets of metallic papers are exposed to a 1,000 watts spotlight, which fades and wears out the material, just like slow torture.

“R.B.” also qualifies to be highlighted. The dialogue between the elements analogs the weariness of a relation, and exposes how in greater closeness, bigger damage can occur. A helium balloon in the shape of a heart is tied and suspended over a cactus. After eight hours, the helium vanishes and the balloon falls over the thorns of the cactus.

Without argument, the strongest section is “C.V.”. Firstly, is where the artist’s desire of connection the two floors of MAVI is carried out. It was constructed simulating a couple’s bedroom, very normal and day-to-day, using sculptures that evoke ancient Rome as a way to complete the atmosphere. A system of strings and stones was hanging over the bedroom, which in a determined movement, hit and destroyed the sculptures. Through this act, the artist was not only referring to the damage two people can provoke within a relationship, but also how the waste from this damage can be accumulated in a dynamic or/and space.

“Being so beautiful does not give you the right to destroy”, gathered a set of other pieces that dialogued from the linking and communication of the parts. Javier’s way of thinking and projecting doesn’t obey to a specific moment. Being the ideas sort of momentary, the process of thinking and digesting these turns longer and is founded on the reflexive process of art. This is way the art piece of Javier Gonzalez Pesce comes together as a supra-structure from connecting the art, which is always long in time.

Español

Español