Currently on show at Schinkel Pavillon, “The Empty House” is the first major solo exhibition of Louise Bourgeois in Berlin. Curator Marie-Ève Lafontaine spoke with Jerry Gorovoy, Bourgeois’ longtime assistant and friend who also oversaw the installation of the show, about Bourgeois’ process of psychoanalysis, her relationship to feminism, and the pleasures of exhibiting in small spaces.

By Marie-Ève Lafontaine | Images courtesy Schinkel Pavillon

“Louise was a really strong feminist…but she always said her work was pre-gender” explains Jerry Gorovoy, referring to the artist Louise Bourgeois to whom he was a close friend and assistant for thirty years. As head of the late artist’s eponymous foundation he supervises the installation of the artist’s work across the world, including her most recent exhibition “The Empty House” currently on exhibit at the Schinkel Pavillon in Berlin.

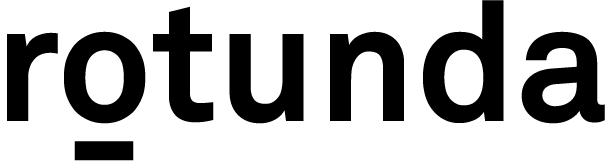

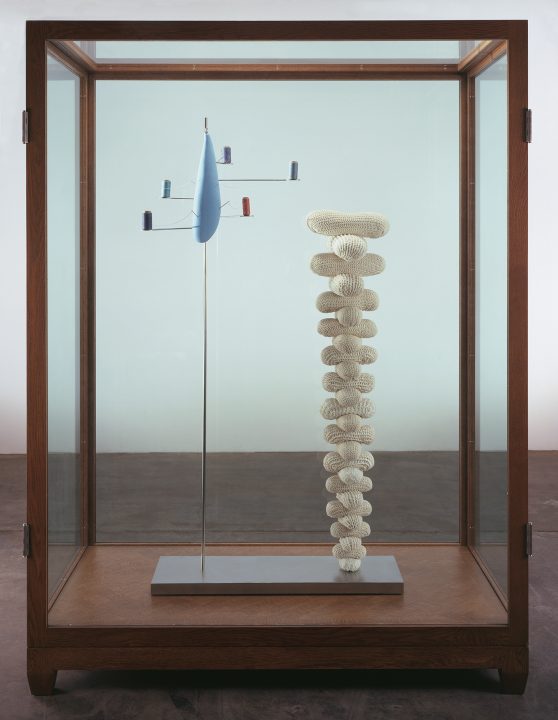

The uncanny fishbowl-like atmosphere of the upper room of the Pavillon, the context within which we first encounter Bourgeois’ work, is remarkable for its panoramic view of the surrounding city center. The tightly curated presentation of almost excruciatingly personal works created over the last decades of the artist’s life is spread over two floors of the mini-institution, whose unrenovated interior strongly reflects the East German aesthetics of the country it once stood in. In such a small space it is hard to avoid the sensation of raw emotions spilling out between the glass vitrines, tiny sculptures and metal grating. However, as usual in the work of Bourgeois, nothing is as it first appears. Grouped thematically around the her use of the ‘sack form’ – a concept which carries deep associations as both a representation of the female body and an architectural structure on its own – many of these works are being shown publicly together for the first time.

We spoke with Gorovoy shortly after the opening about how psychoanalysis affected Bourgeois’ choice of materials, the current effects of feminism on public perception of her work, and the pleasures of exhibiting in smaller spaces.

Marie-Ève Lafontaine: How did the idea for this particular show develop? From what I understand you were thinking about exhibiting these works together for some time.

Jerry Gorovoy: When I saw the space in Schinkel my first thought was that these four vitrines would look beautiful grouped together upstairs in the windowed octagon. Of course, since these works have several very significant conservation issues we eventually realized that was out of the question. As is the case with most exhibitions, the owners, one of whom is the Tate in London, have strong requirements about how such fragile works can be exhibited. In the end we decided to show the relatively delicate vitrines downstairs and the major Cell work upstairs, a decision which in hindsight has been certainly more effective in terms of the overall layout of the show.

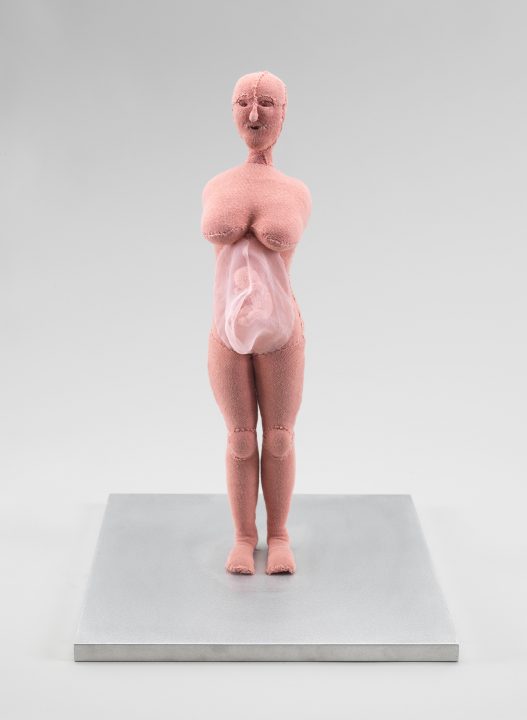

All the pieces shown in Schinkel deal with the ‘sack’ form: every piece has a sack, whether it is opaque or transparent, in one form or another. We also included several smaller pieces in which that idea might not be so immediately obvious: for example, there are several fabric pieces in which the sack is on the torso or incorporated into the sculpture. In the gouaches they are turned upside down and explicitly linked to a female figure.

ML: Obviously the idea of the sack in the context of Louise’s work is loaded with connotations, especially when viewed within the framework of the the psychoanalytical therapy which she underwent for several decades of her life. While researching for the show I realized that actually these sack forms didn’t really exist in physical manifestations until much later on in her career, although they were certainly alluded to in earlier sketches and personal writings. Where does this concept come from?

JG: I think it originated in the sense of an object that ‘contains’, a sort of vessel which is in fact a hosting device for another object or particular atmosphere. The sack form really came out of an idea which Louis explored in her Cell series because in these sculptures she dealt with architectural environments the size of entire rooms. She actually considered the ‘sack’ another kind of architecture, just one made out fabric. The advantage of this material is that is can collapse back on itself very much like living tissue does.

However, the idea of the sack and the idea of the multi-breasted figure was already quite present in her early drawings – she actually explored this idea as early back as the 1960’s. You could say the sacks arose not only out of her desire for self-knowledge but also her interest in architecture since from the very beginning her idea of the figure in relationship to architecture was primarily anthropomorphic. The actual physical form itself is something that she came up with quite late, but the line of the development of the concept was continuous from the very beginning. The sacks are really just an extension and natural conclusion of her use of fabric because of the nature of the material.

ML: The smaller fabric sculptures are especially striking in their method of presentation. They are beautifully imprisoned in these giant vitrines, like the morbid arrangements one usually sees in natural history museums. It seems like an appropriately poetic method of approaching what for Louise must have been a very difficult psychological examination of personal topics; by placing these ‘artefacts’ on the other side of the glass separation she creates a feeling of distance which allows the viewers to examine the personal artefacts more objectively.

JG: In the end the overall presentation worked very well especially in the rougher, un-renovated rooms of the Schinkel Pavillon. For example, in what we call ‘the kitchen’, we choose to exhibit some very delicate gouache drawings. Within the exhibition itself the greatest influence on the arrangement of the works was the three different kinds of spaces which the works were being exhibited in. Upstairs, we had the second floor, with the windowed architecture of the octagon and its curved walls. As you go down to the ground level it becomes darker, which is where we decided to exhibit the vitrines. Lastly you enter the kitchen space which is quite rough, where the smallest vitrine pieces and gouaches are exhibited. I like how the exhibition was organized according to the moods created by the different atmospheres.

“She actually considered the ‘sack’ another kind of architecture, just one made out fabric. The advantage of this material is that is can collapse back on itself very much like living tissue does.”

ML: That is exactly the beauty of the Pavillon. I feel that in a rawer space the viewer is one step less removed from a work of art, in comparison to the interior of a typical white cube which always has the whiff of a clinic about it. Upstairs, the Pavillon itself is actually a sort of vitrine. As you move through the building the exhibition closes upon itself several times over until you come to the most raw, intimate space, where the drawings and small spider are exhibited. This, for me, is Louise’s work at its smallest, most innocent, and most terrifying level. Perhaps you could call it a progression which is not only unexpected but also reflects the greater psychological process as a whole.

JG: As an incredibly intimate space, the Schinkel Pavillon allowed us to carry out a focused exhibition which would not be possible in larger museums. As I said before, the extensive exploration of this particular motif, even though it was quite an important one in her work, has not been done before. Larger exhibitions can be difficult, especially when one is always one step removed from someone else’s work. I like doing this sort of exhibition with a reason in it. Unlike recent international Bourgeois exhibitions, I really enjoy the focus of more intimate kinds of presentations and the the opportunities which they allow. It’s just two completely different things.

ML: I think that also reflects in some way the feeling of the city of Berlin and the Berlin art scene in particular, which is not so flashy as the rest of the international art world. Artists and institutions here don’t have the same feeling of weighty authority, which is of course due in part to the history of the city. Of course this particular exhibition is quite exciting because Louise has never had a major show here before.

JG: No, not in Berlin, her last large institutional show was Haus der Kunst in Munich.

ML: How long was the exhibition in the making and when did you start to plan it with Nina (the artistic director of Schinkel Pavillon)?

JG: The exhibition was about a year and a half in the making. The most difficult part was securing the loans. It was incredibly complicated but luckily it worked out in the end.

ML: Louise’s work in general has a very strong relationship to the female body. As a male and also as Louise’s friend and assistant for thirty years before her death, how do you feel is your own relationship to presenting these works?

JG: Louise was staunch feminist. But in her art she never considered that, she always said that her work was actually pre-gender. It has nothing to do with typical classifications of male or female. Her sculptures are involved with very basic emotional concepts: abandonment, jealousy, all different kind of fears, in a way which is not masculine or feminine in any particular sort of way. The theme of pregnancy, for example, was actually a pivot in her work which pointed towards an antagonism against the father and the classical father figure. On the other hand, as her work evolved there was a gradual unconscious identification beginning with the action of sewing and the figure of the spider which is strongly connected to Louise’s own mother. I think that had to do with her own aging in a way. But it was all very unconscious. In working with old clothes and fabric she was somehow imitating her mother who worked as a tapestry restorer and weaver. This is where the figure of the spider, also a weaver, comes from. It was a unconscious alignment with her mother. I don’t think she even realized that that was the direction that her work was heading. She was simply expressing herself.

“Louise was staunch feminist. But in her art she never considered that, she always said that her work was actually pre-gender. It has nothing to do with typical classifications of male or female. Her sculptures are involved with very basic emotional concepts: abandonment, jealousy, all different kind of fears…”

ML: I was at the Easton Foundation (Bourgeois’ former home) in Chelsea two days ago. It was an eye-opening experience to see first-hand how different elements of the house’s interior were carried over into her artworks. In the Cell series, for example, the perforated metal which she uses for the walls of the enclosure is actually the exact same metal grating which can be found separating the different workspaces in her basement.

JG: Yeah, there was never really a gap between her art and her life. However, in other cases, going back to the themes of pregnancy and birth on display in Schinkel Pavillon as you mentioned before, the references are not always immediately obvious. Louise was not literally referencing her own experience of childbirth. After all she was in her 90’s when she made these – it was more about her wanting to return to the mother. She was the child. Because to be born is in fact to be separated from the mother…you are sort of ejected from the body, and there remains a deep-seated desire to return to this pre-birth physical state. A lot of people misinterpret her work in this regard, particularly in these drawings and gouaches.

ML: Do you feel like sometimes Louise’s work is hedged in by a feminist categorization? I think this is something which female artists encounter quite often in the art world.

JG: In analyzing her work, people tend to use a narrative to try to bring it together. Louise was very formally inventive: she kept shifting in material, scale, and forms over the decades. I think sometimes people look for a method to bring it together in a way that allows them to easily digest her work because of the sheer diversity and power of the types of images, and well as their theatricality. But Louise was very verbal. She wrote a lot and she was very clear about what she was doing and the essential motivations for why she was doing it. In addition to this she was extremely analytical.

“Even though she was in analysis for many years, she always said that she didn’t really trust words. She believed that she had access to her unconscious through making a work of art.”

ML: As I was going over some Louise’s writing at the Bourgeois Archives, Maggie Wright (the director) mentioned that people sometimes approach Louise’s work with a pre-determined reading. The reality of course is that understanding an artwork or an artist is never that simple, especially when you are faced with such a large number of works created over such a long period of time. An artist can never be reduced down to one particular color or flavor.

JG: Louise always said that her work needs no words. You either get it or you don’t. You are visually oriented or you’re not. Most people are good at using what she left as a guide. In fact, she described her work as a voice without a destination… she herself didn’t know what she would end up with. She knew she was feeling a certain way and therefore she had to manipulate the materials in a certain way. Even the choice of the materials stemmed from this feeling. She was just following a path and then when she arrived in a place the work was done. It was never predetermined. She never said to herself “I’m going to start with this concept”. She didn’t say “I want to start with a sack”. She was, after all, complexity even to herself. A form could trigger something in the present, could relate to something in the past, could relate to something she anticipated in the future. Her work gains its extraordinary complexity through its layering of time, modes of association and emotions. However, she was always consistent in her psychological and devotional tenor and her range of expression. She was just formally inventive. In the end after all it is the form that counts; that is really what we have left.

ML: Louise left behind a huge number of personal writings. Did she ever consider herself a poet or did she believe that her activities were merely a necessary extension of her visual artistic creativity?

JG: Louise needed to understand how she was feeling. I think writing gave her certain simplicity, a parallel form of expression in a way, even though she didn’t consider it to be work. There were certain things that she was trying to understand. For example, why she was feeling a particular way or trying to record a memory or why there was something that interested her, such as her sensation of the way someone looked. It was like a parallel stream of activity in another form of passion, but as I said before you can’t always use her diary or her writings to explain her artwork. I think a lot people misuse her own words, whereas they would be better understood as a point of entry into her work. Even though she was in analysis for many years, she always said that she didn’t really trust words. She believed that she had access to her unconscious through making a work of art. Psychoanalysis is really just a process: talking and writing and all that. But Louise had started herself that even before she began formal psychoanalysis. Her earliest diary dates from 1923, when she was twelve years old…even then she had the desire, you could even call it a need, to record how she was feeling. So I think that for her it was a way handling her inner turmoil. Over the course of her lifetime she also saved all her clothes, which is in fact another form of diary, which allowed her to recall people, places and things.

“I think writing gave her certain simplicity, a parallel form of expression in a way, even though she didn’t consider it to be work. There were certain things that she was trying to understand.”

ML: In the basement of the Foundation I noticed the huge amount of boxes. I think there must have been twenty or thirty of them all stacked up.

JG: Yeah, these were the clothes and the sheets and pillowcases that she incorporated in her works.

ML: You spoke about Louise’s desire to express herself in the form of art versus writing, which she mistrusted. Do you think this has to do with the fact that she was living between two languages, French and English, one of which was not her mother tongue? I feel like art, which is experienced visually, generates a more or less visceral reaction because it doesn’t go through a secondary filter, that of language. You could even consider that in Louise’s case there was another a filter, that of culture: she was working and living in a country, the USA, which she only came to know after her she herself was an adult.

JG: This is quite interesting because Louise actually did her psychotherapy in English. As you may know, when a patient undergoes long-term treatment it is usually done in his or her mother tongue. Language, for Louise, was just another tool. She always said that when are working on a sculpture, you do this and the material does that. That means, what you want and what you get is always different. This is because there are scales of resistance according to material: compared to sculpture, there is less resistance in making a drawing, and even less resistance in talking. Resistance, and the way it involves the body – we are talking here about total control – that where the slippage comes in. That is when accidents happen. So there is a resistance in making in sculpture that you don’t have in talking or writing and actually, she loved that resistance, and used it.

ML: Do you think it was because she was looking for methods to control the environment around her and this was somehow one of them? You could say she took pleasure in finding limitations in creating the work of art and that was what dictated her use of material or choice of form.

JG: I think it was more that she was trying to tap into something in a way. Louise felt a certain emotion, but the real work was in locating that emotion and then trying to understand it. That is why she was interested in psychoanalysis. Louise lived very much in the present but when something happened that was intense in the present it caused anxieties. There was always something she was trying to figure out like “what am I afraid of?”, “where did this come from?”, “why do I feel this way?”, “did that happen before?”, “who caused this?”, “what did I do?”. Her works are actually just a manifested form of self-knowledge.

Not so many artists have that intense ability of self-examination. Louise spent thirty years with the same psychotherapist, until 1985. That is quite a big commitment. But she started reading psychoanalytical material even before that, in the 1940’s. She used the psychoanalysis primarily for her creative output. I think she thought that it really helped her with her art. For example, when she began psychoanalysis, she was depressed. Her early pieces were very wooden, rigid, very afraid. They couldn’t stand up. In the course of the analysis she stopped working with wood and she began to focus more on plasticity with containers and holes within holes and hanging pieces and textiles similar to animal layers. The deeper she got into analysis, the deeper she went inside herself. There is a correlation in switching materials and switching forms and all that. The psychoanalysis was very crucial for her artistic development.

ML: So actually she was using her therapy as a form of material in the same way that she used physical material that she was making the art out of.

JG: In a way…yes. I would say definitely.

“The Empty House” runs until July 29, 2018.

*This interview has been edited for length and clarity

Español

Español