“Tente en el aire” was a term reserved for the in-between and undefined identity. The title therefore refers to an inability of fitting into the mathematical structure of identity based on genetic inheritance and points to the immediate flaw in the caste system.

By Àngels Miralda Tena | Images courtesy Kunsthalle Lissabon | Photography: Bruno Lopes

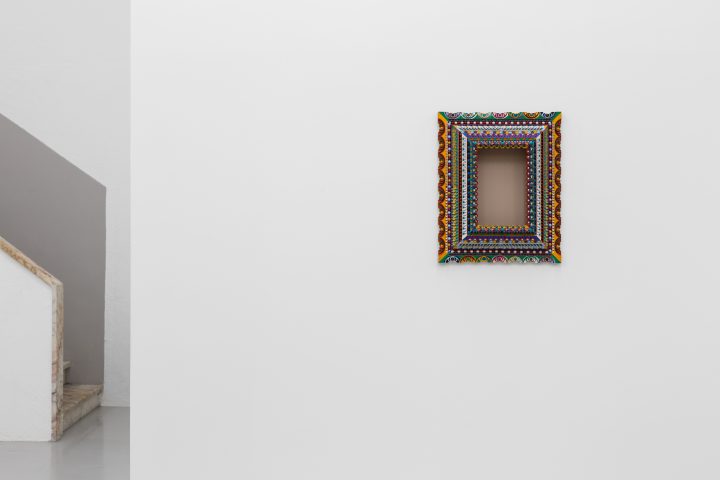

Sol Calero’s first solo show in Portugal Tente en el aire opened on the 15th of May at the Kunsthalle Lissabon. The surprising sobriety of the exhibition compared to recent large-scale installations begs for an explanation which eloquently unfolds in the accompanying text. Earthy tones painted directly on the walls are framed and highlighted by colourful textured frames characteristic of her recent work. The frames don’t contain the paint, which instead spreads underneath them creating a collision between the vibrant crafted wood and murky paint. An uncomfortable combination of strict demarcation between the object and the exposed wall reverses the role of the image causing curiosity at the inversion of painterly structure.

Repeatedly working on the idea of the souvenir and kitsch as representation of Latin-American identity, Calero’s appropriation of colourful frames from Peru follows her line of research. These popular crafts contain images unrelated to their production, pronouncing an exotic touch to whatever content they will envelop. Bringing these frames back to Europe place them in the context as a signifier of a tropical “other” based on their vibrant chromophilia opposed to the Portuguese monochromatic gold-encrusted chapels only a few blocks away.

Kunsthalle Lissabon overlooks the port of Lisbon, providing a context for this exhibition tied to trans-Atlantic missions, trade, and imperialism. Calero’s earthy painting directly on the wall is a reference to the Cuzco school started by early colonists who established an art academy to teach the local populations how to paint “properly.” Operating between the 16th and 19th centuries, the Cuzco school created Saints in an effort to Christianize the colony but also “pinturas de casta” or Caste portraits, which established a “pigmentocracy” in the region based on the purity of European and an elaborate hierarchy of mestizaje.

The paint blasts out from underneath the frames, escaping its structural prison. The frame is not defined as a form of fine art – it is only the support for the prized object that lies inside. In Tente en el aire the world is turned upside-down with both contexts living in equilibrium. The frame itself becomes the object of study while the expressively painted strokes referencing different levels of pigmentations mix and collide into an ambiguous complexion.

Tente en el aire was a term reserved for the in-between and undefined identity. Taken from the colonial hierarchy it refers to a descendent of Campamulato and Cambujo, two denominations of mixed-race individuals. The title therefore refers to an inability of fitting into the mathematical structure of identity based on genetic inheritance and points to the immediate flaw in the caste system. Holding oneself in mid-air might propose a valuable position in contemporaneity of belonging to no land and the inability to put down roots or fit into a biopolitical national categorisation.

In Modern art, the culmination of sculptural formalism and categorzisation by medium appears in Clement Greenberg’s thesis that the three-dimensional is the territory of sculpture and does not belong to painting. Vice versa, Greenberg was known to strip the paint off of sculptures or allow them to rust out of doors in order to reveal their raw materiality. The will to categorize and define carries through the modern era and into today affecting the current art-world interest in definitions of identity. Calero’s inversion in the use of frames and paint directly on the wall dismantles the rigid structures of medium still upheld in the popular imaginary. Similarly, the Peruvian frames defy classifications from the Imperialist mestizo system to the ensuing categorizations of modern and contemporary art.

In light of the declaration made by the shortlisted artists for Berlin’s 2017 Preis der Nationalgalerie – the exhibition is a radical stand against national identity as determining an artist’s worth. It proposes a nuanced approach which takes history, migration, and cohabitation as a condition for a constantly reforming identity which mixes regional practices with global politics of power. The exhibition which marks a defined contrast with its previous “Amazonas Shopping Centre” (2017) shows versatility and range in Calero’s practice and the outcome of on-site research conducted in Peru which in this case, folds back to comment on our own perceptions and production of national identity within the systemized definitions and tokenisms of the art world itself.

Español

Español