Because it’s more than being about the money, Manifesta 11 was about professions. What it means to be an artist, what does it consist of, and how it relates to other disciplines. A reflection about job and our identification with our work.

By Juan José Santos | All images © Manifesta 11

It’s like hitting your head on the doorframe as you enter the house. That’s the feeling this curatorial concept leaves you with, at least in this context. Suggested and evolved by Christian Jankowski (Göttingen, Germany, 1968) for the eleventh edition of the Manifesta, the European Biennial of Contemporary Art. “What People Do for Money”, is the motto of this event located in one of the most expensive cities in the world, Zurich, Switzerland. Home to secret banking and severe migratory control in times of worldwide financial bankruptcy and a growing refugee crisis. That’s what I had been thinking about when the accreditations desk informed to me about the peculiarities of the Manifesta.

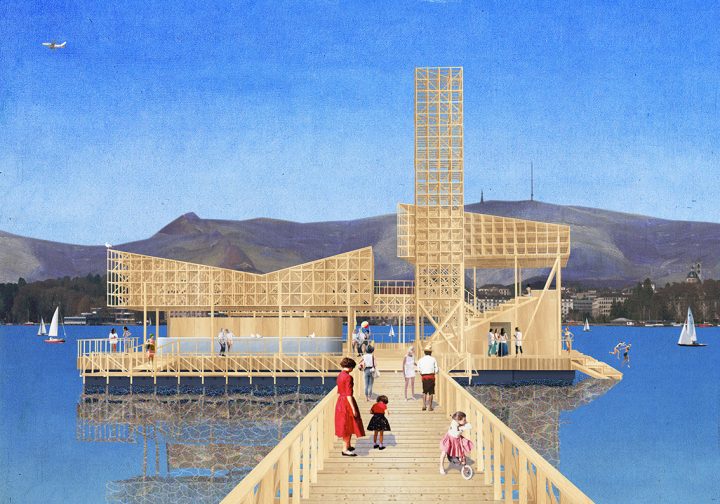

These are the departments: two central bases, under the title “The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction”, where fragments of commissioned creations are displayed alongside historical works, “Satellites”, the new productions by an artist and a professional, alien to the art world, shown in spaces that represent diverse professions. The “Pavillion of Reflections”, a floating platform that shows films about the expositions made by students, called “detectives of art”, and the “Cabaret Der Künstler-Zunfthaus Voltaire”, a series of performances presented in the mystical Cabaret Voltaire, one-hundred years since it’s advent. ‘There are so many things!’, I tell them, only to be met with the answer of, “Ah! There’s also a Street Parade today!”. I raised my eyebrows and I left, ready to discover how “What People Do for Money” fit in with the work of the artists.

I left with my nose stuck to the map, towards the first starting-point, when I began to feel vibrations beneath my feet. Maybe they were the same seismic movements related to the fact that the Swiss masturbate more than any other European country. Turning the corner, I ran into seven men dressed like a sort of sailors jumping down the street to the shout of “bukkake”. Behind them a crowd of thousands of people in costumes that abducted me as if they were a trawling fishnet. A few seconds later, in front of a DJ who played some sort of saturated ‘electro-trash’, a girl dressed as a Pokemon spit in my ear, “Do you have M?”. I searched my bag and doubted for a moment if she was referring to the “M” for Manifesta. I looked into the eyes of the Pokemon. No. She was looking for “M”, as in “Molly”. I was strong and resisted, instead of throwing the exposition guide into Lake Zurich and showing these young people how a critic can move and shake, I opted to say no to all, like a Santiago Serra plan, and be a professional.

Because it’s more than being about the money, Manifesta was about professions (actually the original title was going to be “Vocations”). What it means to be an artist, what does it consist of, and how it relates to other disciplines. A reflection about job and our identification with our work, its end value, and in the end how it’s all a child’s game set with adult rules. “Playing professional” but sparing the consequences.

“The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction”, the section assigned to Francesca Gavin, is composed of two large collective shows plagued by prestigious names such as Thomas Deman, Duane Hanson, Kippenberger, Julian Opie, Ed Ruscha, Harun Farocki, Rosemarie Trockel or Sophie Calle, who live with the works commissioned by thirty international artists (among which there is not a single South American artist). And despite the disparity, of the subdivisions per room, of the absence of a suggested route or the excessive or precarious simplicity of certain works, the result is coherent, lucid, and in some places as acute as acid.

Everything starts with an excerpt from the movie “Solaris” directed by Andrei Tarkovsky. The scene is the encounter between an alien and an astronaut, interrupted by images from the painting by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, “The Hunters in the Snow”. A way to open the suggestive show, that places the viewer before an elusive timeline, and shifts their focus as if they were an extraterrestrial observing a work of art for the first time. A picture, Brueghel’s, which in turn refers to one of the first professions of mankind, if not the first. The exhibition is divided among rooms and possessing themes associated with the idea of a “profession”. Works that are more political-satirical like Gianni Motti’s ‘Bar of Soap’, made from the fat obtained from the center of surgery where Italian politician and media tycoon Silvio Berlusconi attends, or as hilarious as offensive as the video of the laughing fit of Swiss Minister of Finance, Hans-Rudolf Merz. Other works closely linked to the curatorial concept and the setting of Tarkovsky, like the version of Bowie’s ‘Space Oddity’ by Astronaut Chris Hadfield. Indeed, the last two named works are not the works of artists. Other creations are much more elaborate, such as the collaboration between Fermín Jiménez Landa and the local weather man: a sauna that maintains its temperate based on the weather predictions of Zurich. Inside the sauna, there is a fridge, that reminds us of Bob Dylan’s song; You don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows.

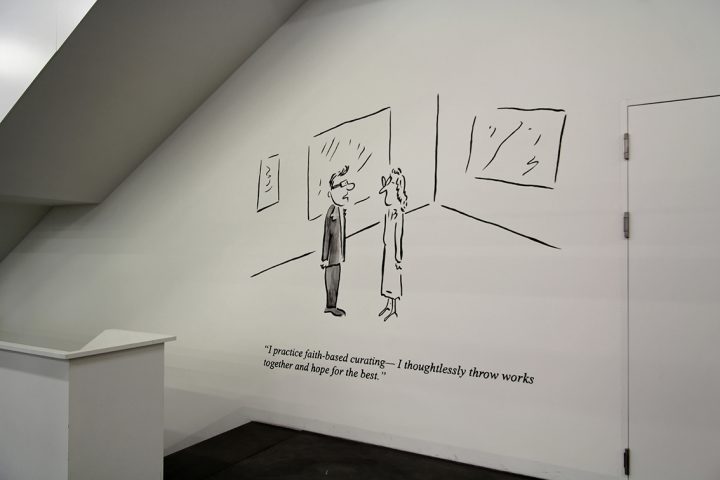

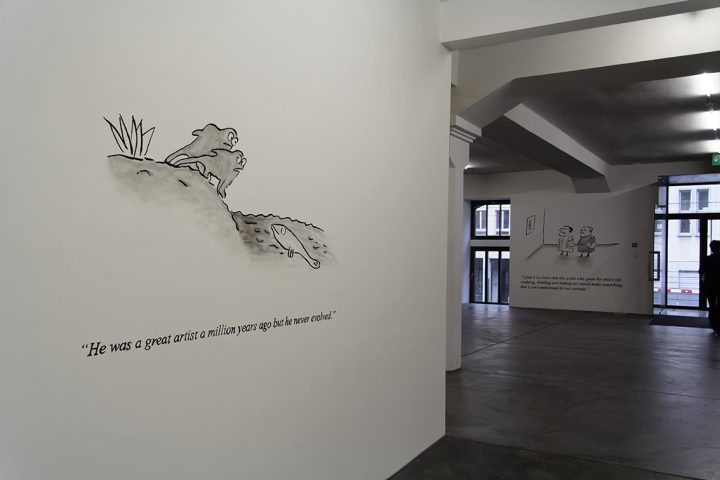

Works covered under the epigraph “The Historical Exhibition: Sites Under Construction”, are compact, refined experiences and at times, very funny. There’s room for self-critical reflection by the art professional, as in the jokes by Pablo Helguera, or the caricatures of Jerry Saltz, Roberta Smith and Hans Ulrich Obrist by Megan Marlatt. Without hiding an attempt of contingent and serious reflection, as with Oscar Bony’s “La familia obrera”, or the commissioned work – and most commented upon of the Manifesta – by Mike Bouchet, “The Zurich Load”, 80 tons of shit, which is what’s generated by the 400,000 habitants of the city each day. Finally there’s a work that speaks, albeit indirectly, about the context in which the exhibition is located. The metaphor is simple: all Swiss, rich or not so rich, natives and immigrants, whatever the profession, make the result: a foul smelling and darkly colored shit. The message is as hard to stomach as the smell coming from the display.

I leave for some air and take a breath again outside the headquarters, ready to hit all of the parallel exhibitions, also known as “Satellites”. Pieces commissioned to an artist in collaboration with a professional from another discipline that are shown in significant locations. These estimates aren’t met in all of the satellite exhibitions which made me come to ask ‘what sense does it make to expand a display in small and remote mini-exhibitions if the chosen locations don’t add or enhance the meaning of the work, as with Leigh Ledare’s video, or other low-impact works, like the uniforms designed by Franz Erhard Walther. We are given the opportunity to appreciate successes like the work by filmmaker Carles Congost with the fire department of Zurich, the ‘miracle’ of seeing a Paralympic athlete cross the lake in a wheelchair, the curiosity of investigating inside the body of artist Michel Houellebecq (something that reminded me of the intestinal endoscopy Fernando Arias did in the inSite of 97’), or the site of a museum by Santiago Sierra.

I find a place to rest in the “Pavillion of Reflections”, in which I can “go back to see” the expositions through the eyes of students, blurring with another lens, the supposed “expert” view of the critic. I finish the day in the mystical “Cabaret der Künstler-Zunfthaus Voltaire”, whose calendar is as hectic as is caotic, perhaps something similar (even though recreated) to what the original dadaist revolution put into practice more than a century ago. I take my notepad out and begin to jot down some ideas: the weight of the background of Christian Jankowski in his works with professionals, alien to the world of art, expositions curated by artists, the success of simple and accessible curatorial concepts, art as a form of fraud, the feeling of specialization and the identification within the craft, Pokemon and her supposed relation with synthetic drugs. I read the catalog texts and translate an enriching doubt raised by the curator; “I find it much more interesting when a work of art celebrates something-being a tribute to something- and simultaneously undermines… Faced with this dilemma, the spectator might ask themselves, “What’s the position of an artist?”

I leave the city with my pockets empty, a happy heart, like Marisol, and with a dilemma to resolve. Beyond the question this brilliant edition of Manifesta asked of me, “What do I do for money”, is a switch of words to ask, “What it is that money does for me?”

Español

Español