The Museo Precolombino of Chile is showing “Reencuentro” by the American artist Sheila Hicks. An exhibition that shines for its colours, textures and scales, which fall from the ceiling in cascades or they show off from small and intimate looms.

By María Victoria Guzmán | Photography: Atelier Sheila Hicks – París

Considered one of the best museums in Chile, the Museo Precolombino was born from an initiative of Sergio Larraín García-Moreno, who in the 1970s realized the relevance of its wide collection of pre-Columbian objects and textiles, creating the Larraín Echenique Family Foundation. This will be the one that donates this important collection in agreement with the Municipality of Santiago to take care of it, study it and spread it; over the years, it has grown with new donations and acquisitions. The collection, for its variety of objects and artifacts, gives a Pan-American look of artistic creation before the arrival of the Spanish highlighted by its textile pieces, Chinchorro mummies and Mayan, Aztec and the natives from the Amazon.

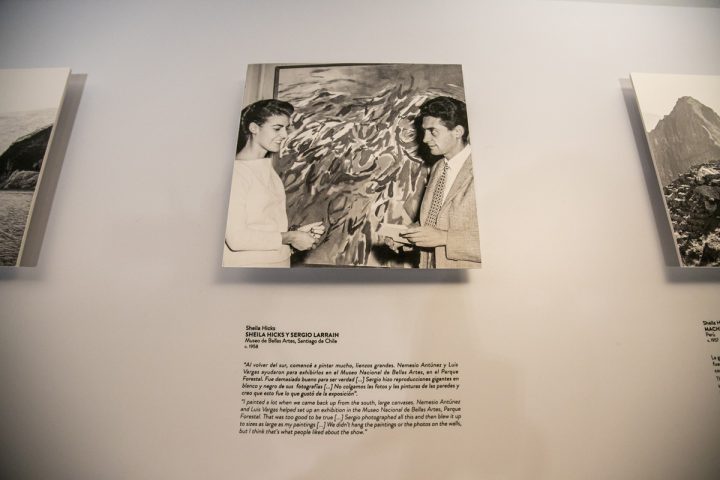

This Museum is showing Reencuentro, an exhibition that contrasts the extraordinary textile work of the American artist Sheila Hicks with various pre-Columbian pieces of the Museum, some of which are shown to the public for first time. Reencuentro is the culmination of a project of the independent curator Carolina Arévalo, who after visiting a Hicks exhibition in New York begins an investigation into the links between her work and the pre-Columbian textile art. Hicks had the chance to know these creations widely in a visit in 1957 to Chile and Latin America, which have strongly inspired her work. She describes the trip as “the beginning of a poem that never ended”, and traveling both the north and the south of the country, she could learn about Latin American textile techniques and worldviews that changed her life and art forever.

Reencuentro is a show that shines for its colours, textures and scales, which fall from the ceiling in cascades or they show off from small and intimate looms. The exhibition links textile art with geometry, crafts and architecture, and contemporary art with pre-Columbian art. It could be a typical case of cultural appropriation: Anglo-sax artist travels to America, learns its techniques and exposes them as her own. This ghost appears in works such as Titicaca Girdles | Atarco | Tiwanaku | Putarco (1957), created the same year of the trip of Hicks, which at first glance seems to be a simple “first world” copy of Latin American techniques. However, a deeper look not only demonstrates the pre-Columbian inspiration, but also the reworking of Hicks, who creates something new and contemporary from the first. Rather than appropriating, the artist appreciates pre-Columbian culture: she publicly recognizes it as inspiration, honours it with her creations and relates to those cultures beyond the aesthetic (as her long journey and subsequent cultural exchange shows).

Reencuentro is a show that shines for its colours, textures and scales, which fall from the ceiling in cascades or they show off from small and intimate looms. The exhibition links textile art with geometry, crafts and architecture, and contemporary art with pre-Columbian art. It could be a typical case of cultural appropriation: Anglo-sax artist travels to America, learns its techniques and exposes them as her own. This ghost appears in works such as Titicaca Girdles | Atarco | Tiwanaku | Putarco (1957), created the same year of the trip of Hicks, which at first glance seems to be a simple “first world” copy of Latin American techniques. However, a deeper look not only demonstrates the pre-Columbian inspiration, but also the reworking of Hicks, who creates something new and contemporary from the first. Rather than appropriating, the artist appreciates pre-Columbian culture: she publicly recognizes it as inspiration, honours it with her creations and relates to those cultures beyond the aesthetic (as her long journey and subsequent cultural exchange shows).

Anyway, since I heard about Reencuentro, I wondered if contemporary Chilean or Latino artists would participate, working on textiles and their relationship with our native peoples, thinking that a contemporary dimension of the pre-Columbian would be beautiful from a local perspective. It was not like that and when I asked the curator, she told me that she considers the exhibition a solo-show of Hicks, which is to me, at least, debatable. An important part of the exhibition are pre-Columbian textile creations, which do have an author (or authors), although we don’t know their names. It seems a lost opportunity to highlight that the exposed Latin American textiles are art, not mere crafts or decorations that accompany the work of the American artist. If we are revaluing the textile, let’s revalue not only a part of it. Let us also highlight the importance of it for our ancestors and ourselves today.

The way in which the objects are exposed echo what the curator expressed: they are not linked to Hicks’ work, since they are shown in cubicles completely separate from the works of the American and the texts fail to create the connections they should, vaguely referring to these relationships with phrases that make almost no sense as “the relationships between beings are reciprocal, in a dimension in which each being passes from one world to another, transforming into another body” (“Ser Textil” (Textile Being), fourth curatorial text). What beings and why is there reciprocity? What dimension are we talking about? What body exactly transforms into another, and why? It reminded me of a 2012 study on curatorial and art texts that concluded that they have their own linguistics that they called “International Art English”, which shines through long words, exaggerations and paragraphs that avoid having any kind of meaning. The same with other texts that refer to memories, stories and messages, which are neither described nor evidence. Memories of whom? What story do they tell? What “specific messages” express the variations of Hicks structures, as written in the second curatorial text? There was a lack of elaboration and connection, something that usually happens (and as I mentioned before, not only in Chile).

The show is divided into four curatorial sections that guide the route from room to room. The first is titled “Thread, Essential Unity.” It pays homage to the thread as a tool of union, an idea that Hicks stands out again and again, for example, comparing the balance of textile to a society in harmony: “touch something concrete with the hands, make a knot with a thread and offer it as a gift to my neighbour. This is more profound and interesting, it is a contribution to the idea of coexisting in this planet together today” she says. She quotes Plato, who distrusted the artists but not the weavers, because by crossing one thread over the other they would have the ability to approach a balanced society, in which all walk in the same direction and progress in unison.

There are echoes of this idea in the quipus exhibited (both from Hicks and the original peoples) that were formerly used to tell, contribute meaning, give information, and that here appears as a metaphor of a community in which everyone counts, means, contributes. From the abstraction of wool, its skeins and combinations of saturation, light and hue, communication ways are born, appearing narrated stories and memories as universal.

In this first section, we find some of the most beautiful and impressive pieces of Hicks. The most denotes a weight, both physical and metaphorical, through which the thread is shown in all its strength and power. Works such as Pescando Anguilas en el Río (1989-2017) of thick flax fibers rotated on themselves; Lianas Rojas (2019) with its cascade of multi-coloured threads; and Quipu Blanco (1965-1966) composed of thick woolen braids. As you can see, the colour is protagonist even in the titles of the artworks and when interacting with the textures of them, it transmits sensations that will be different in each viewer according to the free associations that they could do on white, red, yellow, etc. Another great piece is Araucario (1969), which when mixing linen, silk, cotton and sections of Araucarias suggests a story in which the organic and natural gives life to the work, invading it and creating a symbiotic artifact. The living is also in two sculptural creations that rise in the middle of the room, Peluca Berenjena (1985) and Peluca Verde (1961), since they give the feeling of being creatures that breathe, hairy, and that stand becoming part of the public.

Although this exhibition appears as a synesthetic experience, which involves the visual and tactile, for reasons of conservation of the works, these cannot be touched. However, the richness of their textures, which are enhanced by intense colours, give clues to the imagination of what it would be like to touch and feel with the skin.

Although this exhibition appears as a synesthetic experience, which involves the visual and tactile, for reasons of conservation of the works, these cannot be touched. However, the richness of their textures, which are enhanced by intense colours, give clues to the imagination of what it would be like to touch and feel with the skin.

The second section, “Analogías Compositivas: Arquitectura y Fotografía” explores the aesthetic possibilities of vertical and horizontal textile constructions that we see on Hicks looms. The pieces are accompanied by photographs, some taken by the artist and others by Sergio Larraín, who visually narrate the trip made more than 60 years ago to the American continent. It is relevant that at that time in her life, Hicks came with many influences from Bauhaus, in which design, art and architecture were considered a whole and were explored in an integral way. Despite this, here the relationship between loom, photography and architecture looks forced and the connections that the curator could have done fail to curdle for the visitor. Indeed the looms are constructions, especially Prayer Rug (1972-1973) that with its brown fur it becomes three-dimensional. But in the case of other looms such as Amarillo (1960) and small-scale models of other works, the thread is lost, and it is not understood why they are different from other looms in the previous section, and what exactly gives them that architectural quality that others do not.

The section includes a series of small-scale textiles, which they thrill because of their simplicity, especially after the monumentality of the previous works. Small, humble artefacts, simple in both technique and colour, show a more intimate side of the artist and her practice.

This more introspective and tiny tour continues in “Espacios Cromáticos” with the “minimes”, small fabrics in which she practices the ancestral techniques learned in her trip but taking them on different paths following her own aesthetic through color and scale. It is a tour of the Chilean landscape and memory, with works such as Chiloé-Chonchi (1957), Parque Forestal (1957) and Tacna Arica (1957), in which the loom appears as a figurative work that describes our landscape with its textures and colours. Zapallar Domingo (1957) is a beautiful ode to the well-known cove of the central zone of the country, with tones that evoke thick sunsets between clouds and sea.

“Ser Textil” (Being Textile) is the last section of the exhibition and explores the “sculptority” of Hicks’ works – something frustrating, as it is a subject that has already appeared before. Three-dimensionality is referenced and again I feel that the second section dedicated to architecture does not finish curdling. But we can say that something remarkable, it is the only room in which Hicks’s work is put in conversation with pre-Columbian objects, giving both the same importance, to the point that in certain showcases, at first glance, the date of the pieces are not 100% clear. In contrast, the richness that effectively relates the pre-Columbian and contemporary world becomes evident, since the volume takes on strength when its importance is shown in the pre-Columbian imaginary and in the work of Hicks.

“Ser Textil” ends with three large looms, which at first view play to be paintings. In them, a visual trick makes the interaction of colours of similar hue deceive the brain, making it see more colours than there really is. The description of the effect is disappointingly confusing: “… the colour becomes a phenomenological sensation … expanding the chromatic vision”. A riddle worthy of a sphinx whose answer I could only know by having the privilege of asking the curator.

The work of Hicks is magnificent and offers a deep aesthetic pleasure, not only for the beautiful assembly of the same but also for putting a flourish to a story that began in 1957. It is appropriate, if not precise and necessary, that these artworks return to the place where for the first time the inspirational seed was planted from which Sheila’s art would germinate, and also in a space where they can share with the same works that inspired them. In that sense, there is an undeniable success of Arévalo, who with his perseverance managed to make this show in Chile, an exhibition that had already been exhibited in a similar way in Mexico and soon in Lima. I do not stop thinking that it is unfortunate that the works do not reach a conversation: they remain constantly separated in the route and the descriptions of one and the others do not connect them (with the exception of those shown in the last section), thus not fulfilling the expectations of putting in relief the pre-Columbian as true and powerful inspiration. The relevant thing here is the work of the artist from the United States, with the pre-Columbian occupying second place.

The work of Hicks is magnificent and offers a deep aesthetic pleasure, not only for the beautiful assembly of the same but also for putting a flourish to a story that began in 1957. It is appropriate, if not precise and necessary, that these artworks return to the place where for the first time the inspirational seed was planted from which Sheila’s art would germinate, and also in a space where they can share with the same works that inspired them. In that sense, there is an undeniable success of Arévalo, who with his perseverance managed to make this show in Chile, an exhibition that had already been exhibited in a similar way in Mexico and soon in Lima. I do not stop thinking that it is unfortunate that the works do not reach a conversation: they remain constantly separated in the route and the descriptions of one and the others do not connect them (with the exception of those shown in the last section), thus not fulfilling the expectations of putting in relief the pre-Columbian as true and powerful inspiration. The relevant thing here is the work of the artist from the United States, with the pre-Columbian occupying second place.

Sheila Hicks is introduced by the Museum as “the most important textile artist in the world”. Although Hicks is indeed one of the most recognized textile artists of our time, this type of exaggeration does not contribute, but on the contrary, demonstrates a certain amateurism because they express very debatable hyperboles, if not straight false (especially if we think of other important artists textiles such as Alighiero e Boeti, Jayson Musson, or El Anatsaui). It is difficult to imagine museums like Tate Gallery, MOMA or MACBA doing such absolutist statements and few nuances. It is an art marketing based on the idea of “blockbuster” exhibitions, taking off seriousness from a powerful show. Hicks avoids this type of categorization, recognizing herself as part of a universe of artists who create and experiment with textiles in different ways, each one with his wealth (more about contemporary textile artists here and here).

Sheila Hicks is introduced by the Museum as “the most important textile artist in the world”. Although Hicks is indeed one of the most recognized textile artists of our time, this type of exaggeration does not contribute, but on the contrary, demonstrates a certain amateurism because they express very debatable hyperboles, if not straight false (especially if we think of other important artists textiles such as Alighiero e Boeti, Jayson Musson, or El Anatsaui). It is difficult to imagine museums like Tate Gallery, MOMA or MACBA doing such absolutist statements and few nuances. It is an art marketing based on the idea of “blockbuster” exhibitions, taking off seriousness from a powerful show. Hicks avoids this type of categorization, recognizing herself as part of a universe of artists who create and experiment with textiles in different ways, each one with his wealth (more about contemporary textile artists here and here).

Finally, I was curious to know what Hicks will say about the sponsorship of BHP Escondida, which despite saying they value our heritage and indigenous peoples, has had several encounters with them for pollution and water rights in the north of the country. Nowadays the patronage of companies with this type of conflict is increasingly questioned since the Museums that work with them could be involved in an image laundering that has little ethic. In this case, it is a 20-year alliance that might be worth rethinking.

Español

Español