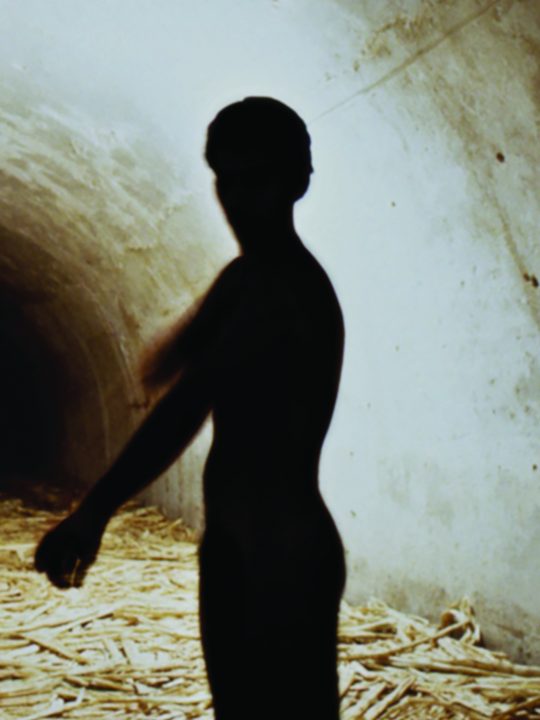

Untitled (Havana, 2000) is a pivotal work in Tania Bruguera’s artistic career. Created for the 2000 Havana Biennial, it consists of a large-scale video installation and a performance. Inside a darkened tunnel, mashed fermenting sugarcane is piled several inches high on the floor, and its sweet-and-sour smell is pervasive. At the end of the long space, a shimmering light originates from a small television monitor that hangs from the ceiling and displays black-and-white video footage of Fidel Castro, who was still the president of Cuba when Bruguera made the work. The charismatic leader appears in different settings, both public and private, delivering speeches before thousands of followers, swimming at the beach, and opening up the shirt of his military uniform to show that he is not wearing a bulletproof vest. Only in turning back toward the entrance does the viewer realize that there are four naked men standing on the mash, quietly rubbing their hands, in a gesture reminiscent of Lady Macbeth washing the blood from her hands in William Shakespeare’s classic play.

The 2000 Havana Biennial, with its theme of “Closer to One Another”, was intended to grapple with communication in an increasingly globalized world. When Bruguera was invited to participate, she submitted several proposals for works that pursued this theme in relation to issues of power, which she had been investigating through her performances and installations. The exhibition’s organizers turned down her proposals, alleging “problems of aesthetic quality,” a charge typically employed by cultural officials in Cuba to silence critical works. When Bruguera’s proposal for an installation using sugarcane mash was approved, they assured her that none was available—a dubious claim in a country famous for its sugar production. Bruguera decided to travel to Havana and to work on site, in the vault at the Cabaña Fortress that had been assigned to her. [1]

The Cabaña Fortress played a significant role in the darkest days of Cuba’s political history. From colonial times to the early years of the Revolution, it was a hot spot for incarceration, torture, and the assassination of opposition leaders. The infamous revolutionary Ernesto “Che” Guevara and the current Cuban president, Raúl Castro, are said to have personally led firing squads there, extrajudicially executing large numbers of people accused of counterrevolutionary activities and spying for the CIA. Bruguera saw an opportunity to address these darker aspects of her native country by metaphorically reviving the art venue’s truculent past. The Havana Biennial purportedly positions Cuba as a center of avant garde art in the developing world.

Since the exhibition venues were located in tourist areas that ordinary Cubans rarely frequent, Bruguera included the naked men to remind the many viewers coming from abroad of the island’s inhabitants, who lack basic freedoms, and to bring the ghosts of the fortress back to life. The artist arranged for the delivery of two truckloads “of pressed sugarcane”. On the eve of the opening, one of the curators visited her to inquire about her plans and, if they passed muster, to grant final approval. Bruguera described the installation and the performance that she intended to carry out within it. The curator was hostile, voicing mistrust of Bruguera, whose work had been temporarily banned some years ago. Ultimately, however, the curator found nothing to worry about in the unfinished installation, and the artist was allowed to proceed. The video showing Castro was not revealed until opening day. Cuban artists rarely show images of Castro, except for laudatory ones, for fear of censorship. Bruguera incorporated images taken from various sources, most prominently a propagandistic documentary by American filmmaker Estela Bravo, a fixture in the Cuban media and known for her pro-Castro stance. In Bruguera’s edited video, the performativity of power through mass media is on full display, especially in the leitmotif of Castro opening his shirt. The contrast between this show of bravura and the docility of the live performers—gesturing, bowing to the image on the television monitor, cleaning their bodies, and standing in a sea of putrefied mash—proved explosive. Dozens lined up to see Bruguera’s work. Only four to five viewers were allowed inside the darkened vault at one time, and there was a long line to get in.

Word quickly spread of a work featuring Castro in a room with naked men. The organizers reacted aggressively, shutting off the electricity, which inadvertently affected an entire section of the show, prompting other participating artists, including foreign ones, to protest. The video component of the work was removed, and Bruguera was barred from resuming the performance the following day. For the remainder of the Biennial, viewers saw only the sugarcane installation, learning about the video and performance through word of mouth.

Untitled (Havana, 2000) signals a turning point in Bruguera’s work in several respects: It marked the first time that the artist left herself out of the performance, instead hiring neighbors and friends, including an actor. Also for the first time, Bruguera sought to control the number of people allowed to access her work at any given moment as a way to subvert the crowdpleasing aims of most international biennials, where success is measured in terms of attendance. She also attempted to undermine viewers’ preconceived political imaginaries by exposing them to more sensorial experiences. Rather than presenting a visual image that requires contemplation, Bruguera wanted to trigger more visceral responses in the viewers.

Untitled (Havana, 2000) had originally been named Engineers of the Soul. The new title was intended to pay homage to the exiled Cuban-American artist Felix Gonzalez-Torres, who customarily titled his works Untitled in order to highlight the viewer’s role in the construction of meaning but often added information, such as the location and date of a specific event, in parentheses. This was not the first time Bruguera honored the work of an exiled Cuban artist. Since 1986 she had been reenacting performances by Ana Mendieta. She also included the work of numerous exiled artists in her underground newspaper Memoria de la Postguerra II (Postwar Memory II, 1994).

Despite the fact that it was censored, Untitled (Havana, 2000) cemented Bruguera’s international reputation. She was subsequently invited to realize a similar work for Documenta 11, in Kassel, in 2002, which led her to reconceptualize Untitled (Havana, 2000) as a paradigmatic approach to responding to the specific memory and history of a place. Major iterations of the project followed in Moscow and Bogotá; a version Bruguera planned for the Israel- Palestine region was never realized.

1. This essay draws on interviews with Bruguera conducted by the author in New York in May and June 2016.

A version of this essay was published on July 21, 2016, on Post, at post.at.moma.org, The Museum of Modern Art’s online resource devoted to art and the history of modernism in a global context.

Español

Español