Ingmar Bergman is the impulse of this stunning artwork of the artist Javier Toro Blum, where a device operates from the sensory opposition, displaying this piece recently exhibited in the latest edition of the Biennial of Media Arts in Chile.

By Ana Rosa Ibañez | Images: Camilo Bustos Delpin

Ingmar Bergman’s “The Seventh Seal” tells us about the insatiable search of Block, to discover through knowledge, the mystery behind life. He needs to undress this secret and look right into his face so he can live a quiet life, or even an early death. For this purpose, he maintains a conversation with Death during a chess match, in which he harasses Death with questions that guide him into the light. Death’s answer is simple: I have nothing to reveal.

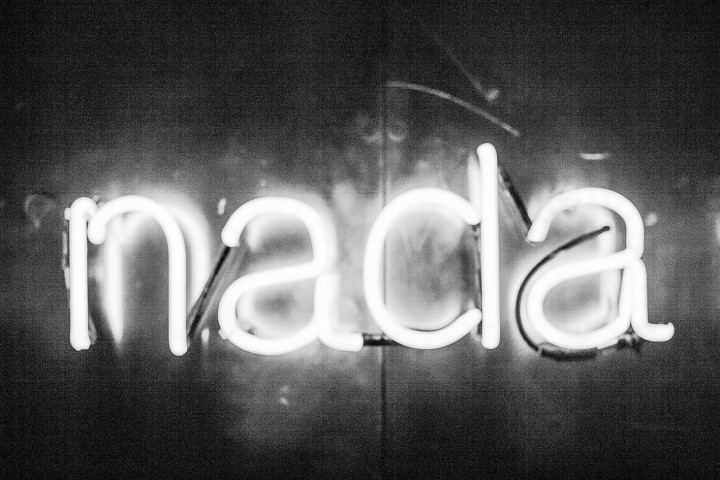

It is from this point where Javier Toro Blum gets the inspiration to produce his piece “Ingmar”, named after the famous cineaste. The artist tries to capture the search of meaning and knowledge that is carried in Block’s character, through light and darkness; work that makes the spectator feel the intrigue in which he is immersed.

Context

This piece wasn’t always as we find it in the Fine Arts Museum for the 12th Biennial for Medial Arts. At first, it just related to film as a general discipline. The structure represented a sculpture of an old auto-cinema’s screen facing a wall. By then, the sculpture referred to the passing of time. By its size, the relation between the space and the spectator was conditioned by the size of the piece. The room was fully in use, so you could appreciate the piece from many perspectives.

When Toro Blum decides to incorporate Ingmar’s text in the piece, he gives a new life to it. For the show in Matucana 100, he uses violet neon lights (this colour is just on the edge of the spectrum, located one step from darkness) and inserts it in a pitch black environment, achieving a visual effect that takes us to Plato’s Myth of the Cave, where people only see a beam of light and have to get closer and around the piece to understand what’s behind it. Just to realize that there’s nothing to reveal.

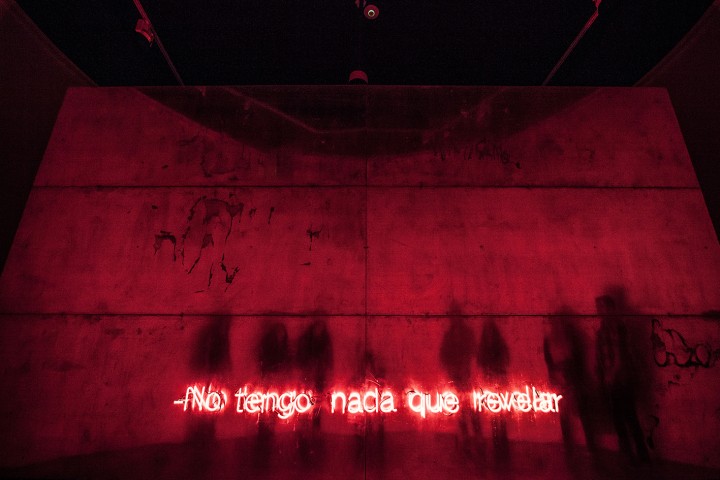

INGMAR (Red)

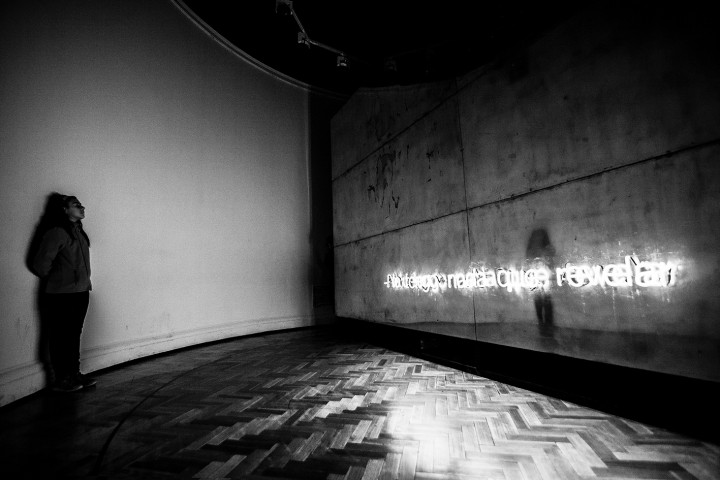

For the biennial’s context, the artist faces a completely different space than Matucana 100’s Concreta Room. The piece has to adapt to a rounded hall and with far less control over lightning. The perception of light needs to shift from optical to special, so the use of colour becomes crucial. This time, Toro Blum chooses red, colour that is located in the opposite edge of the spectrum but also near darkness, being a bit brighter and violet. This way, you can appreciate the colour from a distance, dividing the space with the screen’s silhouette.

Although we cannot talk about a site-specific piece, being that the structure wasn’t specially designed for the space, we can think of the installation as an architectonic device, relating to its obvious dialogue with the space in which it is inserted, activating the bodies that surround it.

The screen or panel that use to be just the support for the text, like movie’s subtitles, becomes a dividing wall that conditions the audience’s route. Seeing the aluminium lit by red neon and stained by the passing of time (the sculpture was kept in a cellar while the artist was studying in London), it reminds us of Richard Serra’s oxidised sculptures. The panel finds its own story against neon, which usually steals the show among materials.

The relation with the piece goes from linguistic and optical and adds corporal and space; here’s where we meet Rivera’s curatorship of “Speaking in Tongues”. Not only film as language but senses as language. The use of senses in order to fully communicate a message.

Is in this process of discovering where we must set our attention. The expectation of knowing what’s behind the screen, Block’s constant existentialism, plays with our conscience of present and being able to incorporate what’s being revealed in that specific moment in terms of light and space, before getting to Death’s answer. We immediately relate light to revelation, while the immersion in darkness is also an important piece of the unveiled truth of the moment.

Español

Español