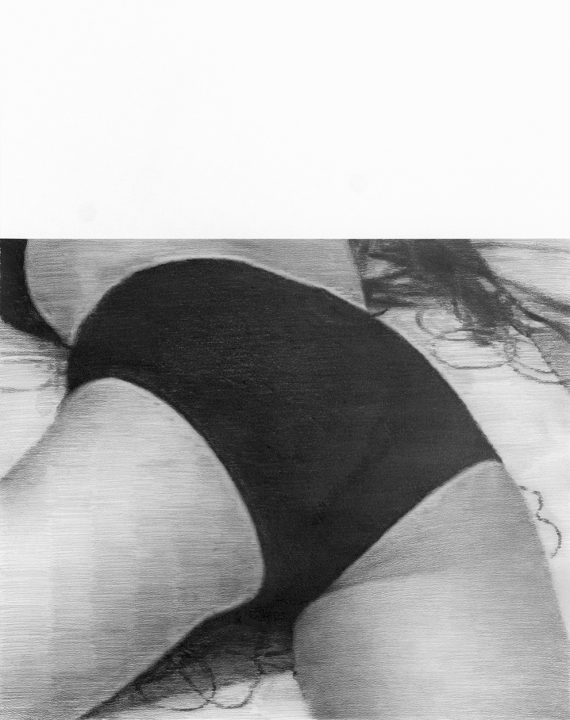

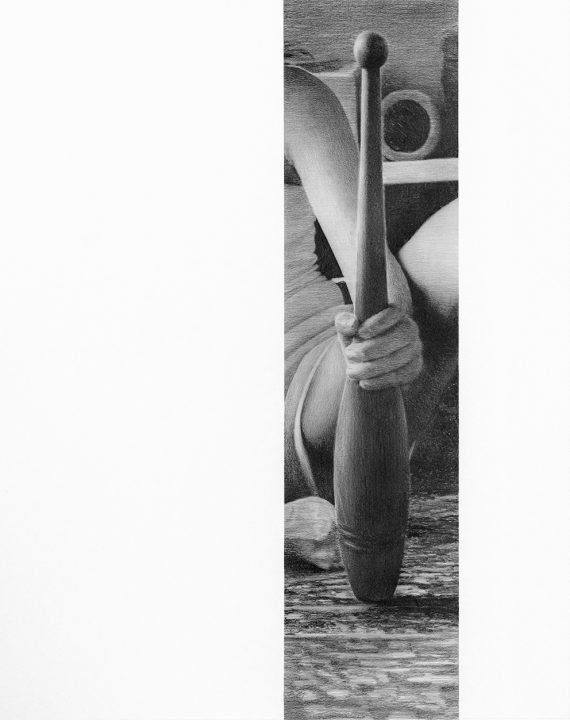

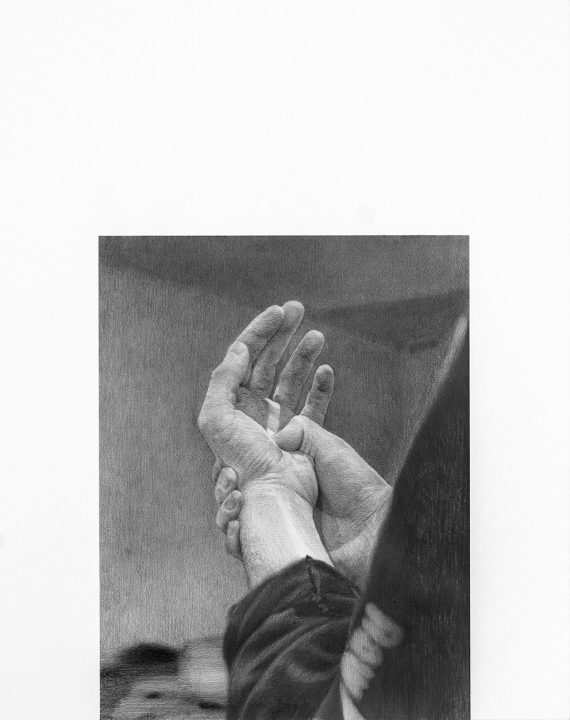

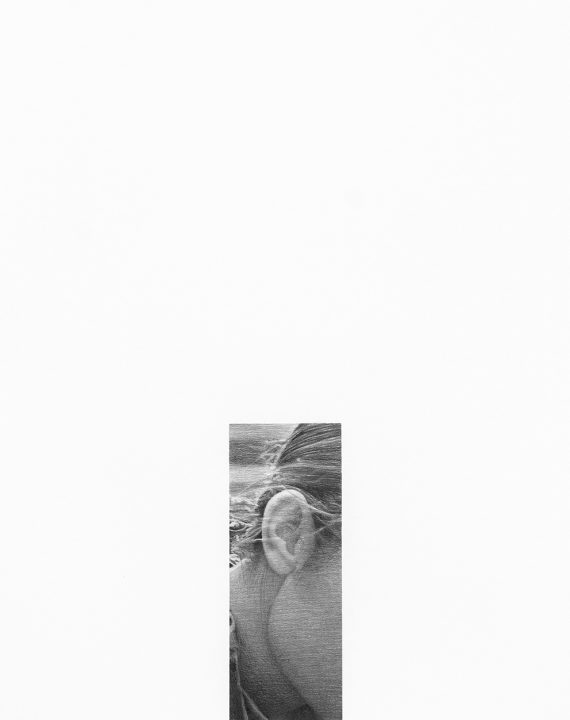

Fragments of a scene

We climb over fences. Getting hold of the trees growing next to them. No one has entered here for a long while. We search for our path through the moist and heavy vegetation.

The spot we find is rocky and covered with bones.

What is it you ask? Fragments of the past, I answer.

It thrills you – I can see it in your eyes.

Are you afraid of your future? Are you afraid of your past?

Naked legs – steps!

Can you hear the water running slowly over stones in the sunlight?

The silence at noon! And the tension of your muscles when we fuck!

Do you sweat? Or did we fight?

The taste of iron on my tongue. Is it your blood?

Touching me feels like fresh meat wrapped in cling film you say.

Do you sleep or did I kill you?

The salt streaming from my skin pours oceans. I drown therein! But shortly after I come to myself again – blazing light, the rustling of leaves in the wind. I am here! I am here! You sing.

Why are the gates bolted so tightly? Why is admittance banned? What do they fear? I follow the xeric texture of your cotton sweatshirt. The fabric is thick and soft! I love that sound. And how it mixes with your breath while you are asleep.

What do you dream of?

I try to imagine the bones inside your body. Silent minerals. Did lovers lie here before? They are building a house nearby. We’ve seen it on our way. You said it won’t last long. What did you mean?

I love the smell of fresh cement – it reminds me of my childhood, when my father took me to one of his building sites. I always wanted him to cast bronze weapons or at least toys for me from the copper and tin he was working with. I was playing in the naked rooms. Blank caves! Pure potential!

You move and I realize you are watching me. Did you read my thoughts? Can you see my very core? I keep thinking while you are walking towards the cold water. You want to jump in before the sun goes down completely. I can sense it.

Things talk to each other silently.

The shape of your bare soles is echoed by the beaks of birds. Silently they perch in the sunlight and clean their plumage. You say: they form a couple – for a lifetime.

The sun is just about to set. But her warmth is still stored deeply in the stones we are lying on. Time blows like slight wind trough endless space. All vanishes!

You sip the crystals out of my palm. They taste bitter.

We are siblings now, you say!

We are alone though!

The cheap white garden chair you are sitting on looks like an ancient creature. Or is it the mask of Saturn? You are naked. Your skin stretches softly around your hips! They look like marble at night!

The warm drops of rain vaporize on the stairs we are descending.

Can you hear that sound?

Is it war drums? Thunder?

Let’s make a child! Or get lost in the landscape!

The lightning hits the trunk close to the bank!

Are we alone?

Follow! Follow!

You sigh!

The Zone!

Tim Plamper, 2017

A peculiar characteristic of this new body of work of Tim Plamper is the exploration of physical experience and of nudity, reconsidered beyond the symbolical clothes left in a precarious balance between desire and cruelty. The artist caresses the phenomenology of disguised contact that Sigmund Freud redefines as rovescio bifronte (two-faced reversal): the touch of Eros and that of Thanatos envelop one another. ‘Bifronte’ comes from the Latin term bifrons, the nickname of Janus (Ianus in Latin), the god of material and immaterial thresholds. He was usually depicted with two faces since he could look both towards the future and towards the past, both inside and outside. Such duality seems to dictate the rhythm of Tim Plamper’s entire work. The artist rethinks the artistic idealisation of nudity, stripping and mixing it, to express ourselves as Georges Didi-Huberman does in his essay Ouvrir Venus (Opening Venus). Focusing on a critique of Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1484-86), Didi-Huberman radically criticises those who set forth and supported the desexualisation of the goddess. This way, they forgot her carnal aspect and purified her from erotism, making her become a “‘celestial’ and closed nude, a nude free of its own nudity, of her own (our) desires, of her own (our) modesty.” Moreover, Botticelli offers Didi-Huberman the possibility of verifying the link between exhibiting nudity and the cruel impulse towards “opening” and desecrating it.

One must thus find the trace of this hidden interchange, in which the touch of Thanatos clutches that of Eros and viceversa, within the Venus herself. It is an imperceptible yet extremely acute transition, during which being touched by the modest beauty of Venus is tantamount to being attracted and almost caressed by her image, while at the same time being struck by the recondite abyss that belongs to the very image. Tim Plamper glimpses the presence of menacing and unsettling aspects beyond the sober beauty of the goddess, and senses her dual nature. He recognises how she experiences an unsolvable dialectic between “apollonian beauty and dionysian violence, the touch of Eros and the touch of Thanatos”, gynaeceum and androceo (male space). She places herself beyond this dialectic and works towards surpassing it.

In Tim Plamper’s refined and meticulous drawings nudity appears like a door that leads us a to a room where beauty and cruelty are ineffably linked. The celebration of the marriage of life and death takes place in this room’s shadowy corners. Here almost every idealisation and construction of the nude lets a hint of disorder and violence seep through. Tim’s works are “shaken” and this vibration represents what precedes and what follows such cruelty. The nude form is born of an aesthetic frenzy, while at the same time moving towards a confusion that renders the form shapeless, and turns this shapelessness into blood.

Domenico de Chirico

Translation from Italian into English by Iante Roach

Re-covering Time in Pictures

“A dream is quite false, absurd, cobbled together from different sources, & yet completely true: it makes, in its unique assemblage, a distinct impression. Why? I don’t know. If Shakespeare is as great as he is said to be, then it must be possible to say of him: it’s all false, it makes no sense – & yet it’s all true according to its own laws.” (Ludwig Wittgenstein)

“I believe in the future resolution of these two states, dream and reality, which are seemingly so contradictory, into a kind of absolute reality, a surreality, if one may so to speak.” (André Breton)

Zeiträume

Tim Plamper dreams with his eyes open, setting up the enigma in broad daylight and creates images that seem right according to their own logic. While it is hard to spell out a single principle by which the interplay of objects, places, scenes, of rhythms and tones in his work could be explained, the logic of dreams and an interest in stratification and spatializing time seem to be part of an explanation.

Some of the works in Tim Plamper’s exhibition Zone recall the altered state of consciousness the artist experienced when he took ketamine, a psychotropic substance. Plamper was particularly captivated by the dissolution of space and time brought on by the drug. But this effect might well have been so fascinating to him because it coincided with something that he had often thought about: spatializing time. The German term Zeitraum (Zeit = time, Raum = space) seems like a perfect word to describe the absorption of time in space that occurs in his works. Far from being purely arbitrary, speaking of temporal phenomena using spatial metaphors could be intuitive and universal. What lies behind us in space often also lies behind in time, and the gestures we naturally make with our hands when talking about the future also seem to confirm that we think of time in terms of space. This has an equivalent in dreams which, according to Sigmund Freud, “transform temporal relationships into spatial ones.” Hence, dreams seem to represent time by space.

In a text on iconic narrative, the film theorist Alain Bergala associates these observations with pictures: “the reserve of space […] created by the depth of field, and, under certain circumstances, by what happens offscreen is always more or less perceived to be a temporal provision.” The impression that something happens offscreen is essential for Plamper’s smaller drawings, which always seem to only render reality partially, leaving out important elements and thus make us imagine much more than what they show. But his iconic stratifications (which also recall photographic overprinting) also inscribe time in space. Their layers are temporal and they show us ghosts from the past that haunt the present.

This temporal approach to pictures has a history. From Antiquity to the Renaissance, single pictures frequently displayed more than one moment, and the same figure often appeared several times in a continuous space. In a painting currently preserved in Vienna, Lucas Cranach the Elder combines all the scenes depicting the fall of man in the Bible into a single landscape: the creation of Adam, the creation of Eve, warning of the forbidden fruit on the tree of knowledge, temptation by the serpent, and finally Adam and Eve’s expulsion from the Garden of Eden.

When Plamper discovered this form of painting during his studies, he was fascinated. He still frequently evokes it when speaking about his own work. While his works are certainly not “history drawings,” he still thinks of the static image as a reserve of time. He thus opposes a tradition that began during the Renaissance, when polychrony was first considered archaic. Since the 18th century, the division between temporal arts and spatial arts has hardly been seriously challenged. Poetry, music, literature, and drama are understood as temporal, whereas drawing, sculpture, and painting are considered spatial media. According to this paradigm, to “spatialize time” in a drawing is to “invade the province of poetry” (G.E. Lessing) and thus to oppose the essence of the spatial media It would seem strange that visual artist have hardly ever tried to challenge the spatiality of pictures since the 18th century, if we did not believe that monochrony is “natural”. The fact is, space still dominates today’s production of artistic as well as ordinary pictures. Photography has certainly played a role in this. After all, its history could be called one of conquering the moment by reducing exposure times, and it is certainly not a coincidence that a central medium of today’s picture consumption is called instagram. Apparently, the promise of immediacy, once associated with cameras with suggestive names such as Express, Presto or Pronto, still pulls us in. What has changed is the nature of the promise made: we are enthralled by the thought of sharing pictures instantaneously around the world rather than the mere possibility of capturing a moment and immediately seeing what we shot. Here (like elsewhere), what appears to be self-evident is what is most interesting. It seems natural that each picture always only captures a single moment, scene, and place. While the unity of time in a picture was indeed challenged at the beginning of the 20th century by Futurism, the challenge posed was rather timid and short-lived. Giacomo Balla’s Dog and person in movement or Girl running on a balcony depicted a few seconds at best and were a far cry from the temporal ranges of medieval paintings, where the whole life of a saint fit into one image. Things were hardly different with Duchamp’s Nude descending a staircase. Perceived as extraordinary experiments, these works seem to confirm monochrony as the paradigm of static images rather than profoundly challenge it.

While it would be quite easy to imagine a camera setting which allows us to condense several shots into a single image, there is now no option that is between filming and a series of shots in burst mode. Monochrony is so deeply entrenched in our way of thinking about pictures that it also governs the way we conceive of technology: in most contexts, overprinting is seen as a bug – at best an experiment – rather than a serious alternative. We generally consider monochrony to be unavoidable. When Plamper superimposes a staircase and a nude, he alludes to Duchamp’s heritage. Hence, Plamper’s post-modernity allows him to connect with a tradition that denies the Modernist notion of the “purity” of drawing. His works cannot, as Clement Greenberg wished, “be seized in a moment’s notice,” nor do they limit themselves to the depiction of a single instant. Based on many sources and experiences – from drugs through Medieval Art to Futurism – Plamper’s works are in fact profoundly subversive, even if they appear classical. What they subvert is nothing less than our vision of pictures.

Re-cover (ies) and materiality

“It is important that the material remains visible. It has to be possible to constantly switch between what it is and what it pretends to be.” (Tim Plamper)

A second seemingly “natural” principle challenged by Plamper’s drawings is the preference of juxtaposition over superimposition. Most creators seem to respect the law of exclusive inscription: as soon as a figure has been placed in a location, this area is no longer available. In art as in life, we usually superimpose things to erase, attack or suppress others. Young children’s drawings, in which the act of creating is more important than reception, show that excessive superimpositions tend to make drawings indecipherable. To avoid the problem of saturation, Plamper works with transparency, both visually and materially.

However, the demands of materiality are not only something that restricts his creativity. Drawing is not only about creating pictures. When assembling and juxtaposing his pieces using Photoshop, Plamper already has drawing techniques and tools he will use for each of the elements in mind: Will he include repetitive strokes or candid scribblings? A paintbrush for leaking effects or the back of a spoon for deeper zones? This variety prepares a rich experience for the viewer: rather than dissolving into a sea of pixels like a photograph when we come close, what we see when we approach, is as interesting as the image that appears from afar.

Plamper’s use of visual layering also has a material basis. Before developing his current technique, Plamper experimented with collage, juxtaposing different images. Some of the “techniques” he now uses were initially accidents of juxtaposition: when he introduces a bright line to create rhythm and guide our gaze, he reproduces the line where two pictures meet in one image and symbolically reminds us of the artificiality of the assemblage. Using a spoon, he truly sculpts in paper so as to obtain different depths and textures.

I’ve introduced the term “re-cover” (Recouvrement) to refer to a trend in modern drawing in which artists cover pictures to recover something else and hide one thing to show another. However, contrary to these practices which approach iconoclasm and where a secondary layer always supervenes on a primary one, Plamper does not just hide pictures or draw on them. Layering lays at the heart of Plamper’s creative process. In this context, it is interesting that stratification already occupied the artist’s mind long before it became a working principle. When he was young, he wanted to be an archeologist. The fascination for anything that is buried still accompanies him.

Digital romanticism

While the topic of the digital appears to be far from an artist whose universe is populated with nudes, stones, waterbirds, and spiral staircases, he also occasionally introduces a symbol that reminds us that he is almost a digital native. Hence, his exhibition includes generic digital color images of the artist and a sunset. But more importantly still, the digital is an inextricable element of his creative process. Photoshop has been such an important part of the artist’s life since his teens that he feels the idea of layers has influenced his worldview and way of thinking. He still spends a very long time looking for the right composition by superimposing layers before he starts to draw. This is part of what he finds interesting in his work because, as he says himself, he is certainly “curious to see the image in the real world, but spending time with the images and the sketches, thinking about the structure, is more important than a single work. I also try to picture the realm of images.” In this sense, Plamper’s works reflect life in a world of changing images, which constantly stack up in our minds. Like Zeuxis, who tried to depict Helen’s beauty by combining traits of the most beautiful women in Greece, Plamper hopes to create an ideal image by combining the most beautiful pictures in his digital archive.

The song of things

“There is a significant difference whether a poet seeks the universal in the specific or finds the specific in the universal. The former approach gives rise to allegory, where the specific is only an example of the universal. The latter however is in fact the nature of poetry. It expresses something specific without thinking of the universal or referring to it.” (J.W. Goethe)

A classic artist, Plamper seeks the universal in what is specific; a romantic artist, he attempts to convey it in a personal way. Finding and assembling the images used in a drawing can take him several years. During that time, Plamper looks for what he refers to as a Bildreim, a visual rhyme, that will resonate with us. When listening to him, often of poets, more, perhaps, than of visual artists. At one point I felt that a poem by Joseph Eichendorff, connected to his quest: “There slumbers a song in all things / As they dream on and on / And the world commences to sing / If only you find the magic word.” Plamper seems to share the poet’s conviction that there is hidden beauty and that there are hidden messages in the objects of this world. The problem is that it we might not be able to grasp them: “Everywhere we seek the Absolute, and always we find only things.” (Novalis) But even if the artist does not know how to decipher the meaning of things, his art can still try to point in the right direction.

In this sense, Chiffre for ten dispositions (2015) is programmatic: the work shows a photograph of a plastic chair, upside down most of the time, being played with by the wind. During a rainy vacation, the artist recorded its movements for several days. Chiffre associates each of the ten photographs with a line drawing. Each of the drawings is like an abstract sign which the position of the chair could convey; a magic line rather than a magic word; an attempt to capture the linear essence of a thing in drawing. When he showed the work in an exhibition called The space of words is not the space of images (2015), the artist warned us: the meaning of the visual cannot be captured in words. We would need to know another language. I might even be that ordinary language – or at least the way we use it – prevents us from seeing rather than helping us observe. According to René Magritte, “the habit of speaking for the sake of life’s urgent needs imposes a restrictive sense on the words which designate the objects. Ordinary language seems to place imaginary boundaries around imagination.” But Magritte was confident that art can help: “we can create new relationships between words and objects and specify certain characteristics of language and objects which are generally ignored in our day-to-day existence.” Like Magritte, Plamper draws connections between objects which generally remain unexplored and invisible, and his work seems to oscillate between the attempt to capture something that cannot be said in words and the fear that it cannot be spelled out.

I would like to make one last remark about Chiffre. At first glance, the work’s content and form appear to be radically different from that of the artist’s other works. Firstly, Chiffre’s minimalistic aesthetics evokes conceptual and neo-conceptual art. Secondly, it seems to be based on a process of abstraction and radical reduction, whereas his other creations work with superimpositions. But to see things this way means to forget the constructed nature of his re-coveries. To bring two far-away elements together spatially or to even superimpose them is to affirm that they are related – and their relationship could very well be based on a common structure like the one revealed in Chiffre. This formally minimal work would then be based on the same underlying analysis as his most visually complex creations from 2017: Plamper teaches us that one of the things a spiral staircase and a human figure have in common is their linear essence, a helix.

Opposing our most common ideas on the nature of pictures, mimetic and material, analogue and digital, flat and stratified, Tim Plamper’s works depict what cannot be said. They are enigmas to be deciphered over and over again.

Klaus Speidel, art critic and philosopher

Translated by Rena Katikos

Tim Plamper

Born in Bergisch Gladbach, Germany

Lives and works in Berlin, Germany

Installation views © Rebecca Fanuele

All images courtesy Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve

www.timplamper.com

www.instagram.com/timplamper

www.suzanne-tarasieve.com

www.instagram.com/galerie_suzanne_tarasieve

Image 01: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Image 02: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Image 03: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Image 04: Fragments of a scene 001 – 012, pencil on paper, 59 x 47 cm, 2017

Image 05: Fragments of a scene 001 – 012, pencil on paper, 59 x 47 cm, 2017

Image 06: Fragments of a scene 001 – 012, pencil on paper, 59 x 47 cm, 2017

Image 07: Fragments of a scene 001 – 012, pencil on paper, 59 x 47 cm, 2017

Image 08: Hermaphrodite, wallpaper, 310 x 650 cm, 2017 Edition: 3 plus 2 E.A.

Image 09: Dissociation 003 (Your Skin is my Skin), pencil on paper, 200 x 150 cm, 2017

Image 10: Dissociation 001 (The Line of Time), pencil on paper, 200 x 150 cm, 2016

Image 11: Dissociation 004 (The Hearts Shadow), pencil on paper, 196 x 254 cm, 2017

Image 12: Sun, wallpaper, 270 x 380 cm, 2017. Edition: 3 plus 2 E.A.

Image 13: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Image 14: Zone, c-print, 19,8 x 15,4, 2017. Edition: 8 plus 2 E.A.

Image 15: Melancholia, pencil on paper, 253 x 196 cm, 2017

Image 16: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Image 17: Installation view “Zone” at Galerie Suzanne Tarasieve © Rebecca Fanuele

Español

Español